A new report from the Manhattan Institute supports what law enforcement and drug policy experts have long understood: the majority of fentanyl entering the U.S. does not come from Canada, despite the White House’s claims.Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Jonathan Caulkins is professor of operations research and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College. The views expressed in this piece are the author’s own and do not represent those of the university or any other organization with which he’s affiliated.

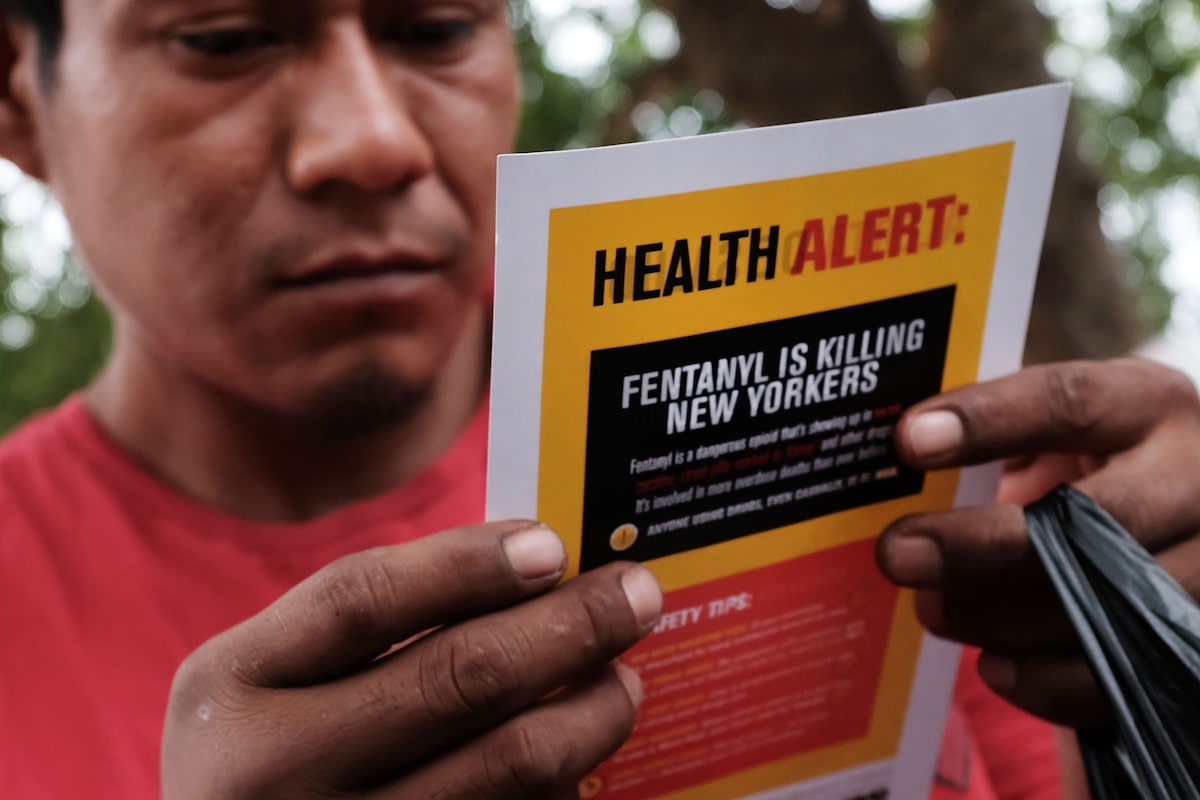

Illegally manufactured fentanyl is a national tragedy – one that has taken hundreds of thousands of American lives and almost the same proportion of Canadian lives. Addressing the crisis deserves serious, data-driven policymaking. That’s why it’s troubling that recent rhetoric from the White House has singled out Canada as a significant source of fentanyl flowing into the United States, even citing this as one reason for the application of tariffs on Canadian goods.

Let’s be clear: the data do not support that claim.

In a new report I co-authored for the Manhattan Institute, we analyzed nearly 200,000 heroin and fentanyl seizures across the U.S. from 2013 to 2024 as recorded in multiagency enforcement task force data. We focused on large seizures – over one kilogram of powder or more than 1,000 pills – because those quantities are likely tied to wholesale trafficking, not personal use. Our findings reinforce what law enforcement and drug policy experts have long understood based on other data: the overwhelming majority of fentanyl entering the U.S. comes through the southern border, not from the north.

Vast majority of large U.S. fentanyl seizures happen along Mexican border, report finds

How overwhelming? Between 2013 and 2024, 99 per cent of the fentanyl pills and 97 per cent of the powder in large land-border seizures were intercepted along the U.S.–Mexico border. In the past two years, counties along that southern border, which make up only 2.35 per cent of the U.S. population, accounted for nearly 40 per cent of the total fentanyl quantity seized in large busts.

By contrast, counties along the northern border with Canada accounted for just 0.5 per cent of the pills and 1.2 per cent of the powder. Even Wayne County, Mich., which includes Detroit and had the most sizeable seizures of any county bordering Canada, saw amounts that were not more than what one would expect for a city of its size. There’s no indication that its location on the border was the cause.

White House using misleading fentanyl data to justify tariffs

Yes, there are rare and minor exceptions. A 2023 enforcement action in Okanogan County, Wash., took down a Mexican-led trafficking group supplying rural parts of the Pacific Northwest. Whatcom County, also in Washington, may see some spillover across the border from Vancouver. And Alaska, geographically isolated from much of the U.S., may receive some supply via Canada.

But those are local anomalies, not the rule. Taken together, all the fentanyl seized near the Canadian border represents barely more than rounding error in the national data.

More importantly, Canada is not the adversary in this crisis. The United States and Canada are in the same boat – both are destination markets challenged by deadly fentanyl. Both countries have suffered staggeringly high overdose death rates from synthetic opioids over the past decade. The rise in deaths began around the same time on both sides of the border, and encouragingly, the declines that began roughly 18 months ago have also manifest in both the U.S. and Canada. The upstream source of the fentanyl problem lies neither within the U.S. nor within Canada: the chemicals from which fentanyl is produced mostly originate in China and flow through global trafficking networks, in the U.S. case particularly those run by Mexican cartels.

Fighting a shared challenge calls for closer collaboration, not confrontation. Better coordination between U.S. and Canadian law enforcement can help plug small cross-border flows – such as those into Alaska or Whatcom County – but those flows are not the main event. The far greater challenge lies at the southwestern border and in the postal and freight systems that bring in precursors from overseas.

None of this means the U.S. should ignore northern border security. But the suggestion that Canada is a major source of America’s fentanyl problem is simply not supported by the evidence. And it doesn’t justify economic penalties like tariffs, which do little to address the opioid crisis and do much to damage one of America’s closest allies – and the U.S. itself.

North America’s opioid epidemic is complex, and no single policy will solve it. But effective supply-side interventions must begin with an accurate picture of the problem. If the U.S. wants to disrupt the trafficking networks fuelling this crisis, its efforts should remain focused on the southwestern border, international shipping channels, precursor flows, and the transnational criminal organizations that exploit them – not on scapegoating its neighbour to the north.