Jerome traveled a thousand miles from California to El Paso, Texas, so he could accompany Jenny to her immigration hearing. He and his wife had promised to take her after she had fled Cuba last December, after the government there had targeted her because she had reported on the country’s deplorable conditions for her college radio station.

Everything should have been fine. Jenny, 25, had entered the United States legally under one of Joe Biden’s now-defunct programs, CBP One. By the end of the year, she could apply for a green card.

But a few days before her hearing, Jerome started to feel like something was off. Jenny’s court date had been abruptly moved from May to June with no explanation. Arrests at immigration courthouses peppered the news.

And when Jenny went before the court, the government attorney assigned to try to deport her asked the judge to dismiss her case, arguing vaguely that circumstances had changed.

Federal agents escort a family to a transport bus after they were detained following an appearance at immigration court in San Antonio on 22 July 2025. Photograph: Eric Gay/AP

Instead, the judge noted that Jenny was pursuing an asylum claim and scheduled her for another court date in August 2026 – the best possible outcome.

“She turned around and looked at me and smiled. And I smiled back, because she understood that she was free to go home,” Jerome said.

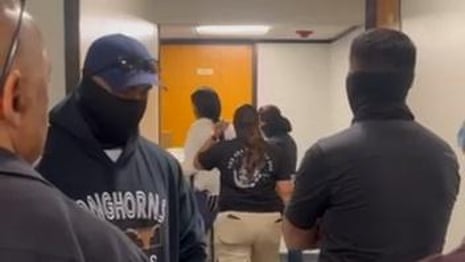

But as Jenny left the courtroom and approached the elevator to leave, a crowd of government agents in masks converged on her and demanded she go with them. Just before she disappeared down a corridor with the phalanx of officers, she turned back to look at Jerome, her face stricken, silently pleading with him to do something.

“I said, ‘She’s legal. She’s here legally. And you guys just don’t care, do you? Nobody cares about this. You guys just like pulling people away like this,’” Jerome recalled telling the agents. “And nobody said a word. They couldn’t even look me in the eye,” he told the Guardian.

Footage of her apprehension was taken by those advocating for her and shared with the Guardian.

Woman arrested in California immigration courthouse – video

Woman arrested in California immigration courthouse – video

Now Jenny is languishing in immigration custody. Her hearing for August 2026 has been replaced with a date for next month when the government attorney might once again attempt to dismiss her case, and her case been transferred from a judge who grants a majority of asylum applications to one with a less than 22% approval rate.

“There’s no heart, there’s no compassion, there’s no empathy, there’s no anything. [It’s] ‘We’re just going to yank this woman away from you, and we don’t care,’” Jerome said. The Guardian is not using his or Jenny’s full name for their safety.

Similar scenes have played out again and again at immigration courthouses across the country for weeks, as people following the federal government’s directions and attending their hearings are being scooped up and sent to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) detention.

The unusual tactics are happening while Donald Trump and his deputy chief of staff for policy, Stephen Miller, push for Ice to make at least 3,000 daily arrests – a tenfold increase from during Biden’s last year in office. Ice agents have suddenly become regulars at immigration court, where they can easily find soft targets.

At first, the officers appeared to focus arrests on a subset of migrants who had been in the US for fewer than two years, which the Trump administration argues makes them susceptible to a fast-tracked deportation scheme called expedited removal. Ice officers seem to confer with their agency’s attorneys, who ask the judge to dismiss the migrants’ cases, as they did with Jenny. And, if judges agree, the migrants are detained on their way out of court so that officials can reprocess them through expedited removal, which allows the federal government to repatriate people with far less due process, sometimes without even seeing another judge.

Detainees in the yard of the Bluebonnet detention facility, where Venezuelans at the center of a supreme court ruling are held, in Anson, Texas, on 24 April 2025. Photograph: Mike Blake/Reuters

But reporting by the Guardian has uncovered how Ice is casting a far wider net for its immigration court arrests and appears also to be targeting people such as Jenny whose cases are ongoing and have not been dismissed. The agency is also snatching up court attendees who have clearly been in the US for longer than two years – the maximum timeframe that according to US law determines whether someone can be placed in expedited removal – as well as those who have a pathway to remain in the country legally.

After the migrants are apprehended, they’re stuffed into often overcrowded, likely privately run detention centers, sometimes far from their US-based homes and families. They’re put through high-stakes tests that will determine whether they have a future in the US, with limited access to attorneys. And as they endure inhospitable conditions in prisons and jails, the likelihood of them having both the will to keep fighting their case and the legal right to stay dwindles.

“To see individuals who are law-abiding and who have received a follow-up court date only to be greeted by a group of large men in masks and whisked away to an unknown location in a building is jarring. It breaks my understanding and conception of the United States having a lawful due process,” said Emily Miller, who is part of a larger volunteer group in El Paso trying to protect migrants as best they can.

One woman Miller saw apprehended had come to the US legally, submitted her asylum petition the day of her hearing, and was given a follow-up court date by the judge before Ice detained her.

“My physical reaction was standing in the hallway shaking. My body just physically started shaking, out of shock and out of concern,” Miller said. “I have lived in other countries where I’ve been a stranger in a strange land and did not speak the language or had limited language abilities. And as a woman, to be greeted by masked men is something we are taught to fear because of violence that could happen to us.”

Elsewhere in Texas, at the San Antonio immigration court earlier this month, a toddler dressed in pink and white overalls ran gleefully around the drab waiting room. Far more chairs than people lined the room’s perimeter, as if more attendees had been expected. A constantly multitasking employee at the front window bowed her head in frustration as the caller she was speaking to kept asking more questions. Self-help legal pamphlets hung on the wall – a reminder that the representation rate for people in immigration proceedings has plummeted in recent years, and the vast majority of migrants are navigating the deportation process with little to no expert help.

skip past newsletter promotion

Sign up to This Week in Trumpland

A deep dive into the policies, controversies and oddities surrounding the Trump administration

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

In one of the courtrooms, a family took their seats before the judge. Their seven-year-old boy pulled his shirt over his nose, his arms inside the arm holes. The government attorney sitting with a can of Dr Pepper on her desk promptly told the judge she had a motion to introduce, even as the family filed their asylum applications. She wanted to dismiss their cases, she said, as it was no longer in the government’s best interest to proceed.

The judge said no. She scheduled the family for their final hearings just over a year later. And she warned them, carefully, that Ice might approach them as soon as they left her courtroom. What happened next, she said, was not in her control.

Her last words to the family: “Good luck.”

Men in bulletproof vests were hanging around in the hallway, but the family safely made it into the elevator and left the courthouse for the parking lot. Stephanie Spiro, associate director of protection-based relief at the National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC), said that for the most part, Ice is leaving families with children alone (with notable exceptions). It’s “single adults” they’re after, people who often have loved ones in the US depending on them, but whose immigration cases involve them alone, she said.

A few days later, two such adults – a man and a woman – separately went before a different immigration judge in San Antonio, whose courtroom had signs encouraging people to “self-deport”, the Trump administration’s phrase for leaving the country voluntarily before being removed.

The government attorney that day moved to dismiss both the man’s and the woman’s cases, which the judge granted, dismissing the man’s case even before the government attorney had given a reason why.

Using a Turkish interpreter, the judge then told the man it was likely that immigration authorities would try to put him into expedited removal – despite the fact that he had entered the US more than two years earlier.

Soon after, the woman – who had been in the country for nearly four years – went before the court without a lawyer. The judge tried to explain to her what might happen if her case were dismissed, but as he finished, she admitted in Spanish: “I haven’t understood much of what you’ve told me.”

A man on a bus behind tinted and barred windows after he was detained by federal agents following an immigration court appearance in San Antonio on 22 July 2025. Photograph: Eric Gay/AP

The woman went on to say that she was deep in the process of applying for a visa for victims of serious crimes in the US – a visa that provides a pathway to citizenship. But the judge was upset with her for not also filing an asylum application, and he threatened to order her repatriated. It was the government attorney who “saved” her, the judge said, by requesting the case be dismissed instead.

As soon as the woman walked out of the courtroom, agents approached her and directed her out of the hallway, into a small room. Around the same time, outside the building, men wearing gaiters over their faces ushered a group of people into a white bus, presumably to be transported to detention.

Spiro of the NIJC, meanwhile, works in Chicago and said she and fellow advocates have documented Ice officers in plainclothes coming to immigration court there with a list of whom they’re targeting – and court attendees are apprehended whether or not their case is dismissed.

“People are getting detained regardless,” Spiro added. “And once they’re detained, it makes it just so much harder to put forth their claim.”

Migrants picked up at the court in Chicago have been sent to Missouri, Florida and Texas – to detention spaces that still have capacity, but also to where judges are more likely to side with the Trump administration for speedier deportations. Many of them end up far from their loved ones, and a lag in Ice’s publicly accessible online detainee locator has meant some of them have at times essentially disappeared.

As word of mouth has spread among immigrant communities in Chicago about these arrests, the once bustling court has gone eerily quiet, Spiro said. That, in turn, could have its own serious consequences, as no-shows for hearings are often ordered deported.

“They don’t want to leave their house because of the detentions that are happening,” Spiro said of Chicago’s immigrants. “So to go to court, and to go anywhere – they don’t want to come to our office. To go anywhere where there’s federal agents and where they know Ice is trying to detain you is just terrifying beyond, you know, most people’s imagination.”