As boomers retire, there simply aren’t enough young people born in the UK to replace them. That’s why migrants are stepping in — and why we need them. With US evidence and UK parallels, I show how migration supports our economy, pensions, and future security.

The audio version of this will be available later.

This is the transcript:

One of the most difficult topics to talk about when it comes to economics is the economics of migration.

Now, for me, this is a personal issue. I come from a family of economic migrants. The clue is in my name, and it’s not just in my name, but it’s actually in my wife’s name as well, because she’s a hundred per cent genetically Irish and we have a very large extended family, almost all of which is in the UK and almost all of whom are economic migrants.

So I find the issue of economic migration, and a lot of the nonsense talked about it, really quite offensive because I resent any suggestion that I haven’t added value to this country, and I look around my wife’s family and other members of my extended family and think, we’ve done good things for this country, and so we need to talk about this issue of the economics of migration.

And Paul Krugman, the US-based Nobel laureate economist, did a column on this on 20th July on Substack, and he had a lot of data in that column, which is only available in the USA, but which gives clear insights into what is happening on migration in that country, and, as far as I can see, every situation that he describes is likely to be the same in the UK, and so we can use his data and his sources to understand better what the issues around the economics of migration are.

And let’s be clear, the issue is deeply politicised and very often on the basis of race, and let’s not ignore that, and I won’t ignore that because that’s personal as far as I’m concerned.

But what I want to talk about are the facts, and let’s stick to those because that matters.

The reality is that the claim that migrants are somehow threatening the US labour force, or the UK labour force, is not supported by data.

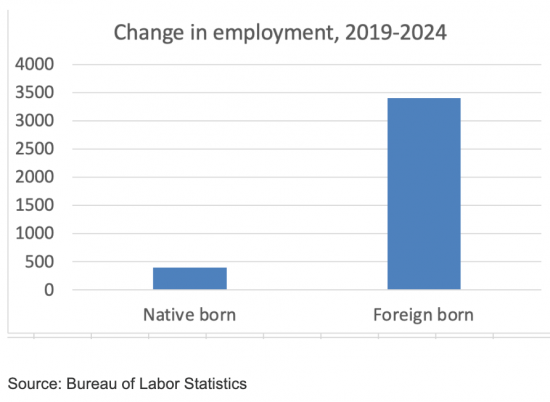

And the data that we’re looking at here is the increase in employment in the USA between 2019, in other words, the year before COVID, and 2024, in other words, well after COVID was becoming history in employment terms. And what you’ll see is that employment in the USA rose over this period, quite significantly, and where did those new employees come from? The vast majority, as you will note, were foreign-born.

They were new migrants to the USA. And we have the same situation in the UK. Very large numbers of people entering the labour force in the UK are going to be migrants for one very simple and very straightforward reason, which is the same in both the USA and the UK.

We are not replacing our working population with new young people born in the country. In other words, as boomers – people of my age – come to retirement, they are not capable of being replaced by new young people who are their children or grandchildren because there just aren’t enough of them. Therefore, if there’s to be employment growth or even employment maintenance, we need migration. Without migration, in fact, economic growth in both countries would fail. It’s a simple, straightforward fact.

And what is more, it wouldn’t just fail. It could seriously reverse, which has massive consequences for the security of those who are entering old age, because it is the people from following generations who will supply people who are in retirement with the income that they need in order to sustain them.

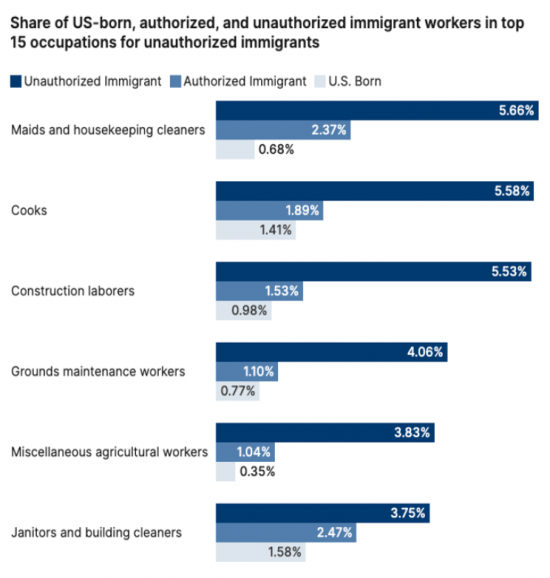

So migrants are important, but they’re particularly important in some economic areas. In particular, this is again true for the USA and for the UK. Migrants dominate work in tough, low-paid sectors. Let’s again just look at some of this data. Migrants are most commonly found in things like construction, agriculture, food preparation, the hospitality industry and care homes.

This chart gives some indication of this. It’s US data, but it will give you some indication of what we are looking at.

There are carers; there are construction workers, there are people who are cleaners and janitors, to use the US term, and so on, in that group of the highest occupations dominated by migrant workers, and the people who were born in the USA don’t want to do those jobs.

So those fundamental roles, which keep the economy going, are being supported by migrant workers. Yes, they’re low-paid, and yes, they appear to be those which require low qualifications, although that doesn’t mean to say that the people doing them necessarily do have low qualifications, but the point is, they’re also essential, and almost none of them are capable of replacement with AI.

So these jobs aren’t being stolen, as some people like to claim that migrants do. They’re actually genuine vacancies being created by boomers retiring that have to be filled, and there aren’t people born in the country to replace those who are leaving the market because they are, as I’ve said, retiring.

So if you deport migrants, and of course that is the policy of the Trump regime, and I use the word regime wisely in the USA, what you actually find is that vital services and supply chains will break down.

And exactly the same thing would happen here in the UK if that were to happen.

If I look at the fields in the area around where I live in East Anglia. I won’t see almost any British-born workers. These are the most productive fields in the UK. They produce more of our salad crops than anywhere. They produce more of our wheat than other parts of the country, and they are vital to the supply of potatoes in the UK, and the people who are doing that work are all migrants.

This is not because local people don’t want jobs. They really don’t want to work in the fields, and migrants will.

So what we’re seeing, if we have an anti-migrant policy, is a deliberate policy of economic destruction. And let’s be clear about that. Once you force migrant labour out of the market, you’re going to have to pay much higher prices to get other people to come in to do these jobs, which British-born workers don’t want as a matter of fact. That will necessarily fuel inflation, and this is going to be one of the big consequences of the policy pursued by Trump, and which Nigel Farage would also like to pursue, and to some extent, Labour is promoting as well.

We would see food production fall.

We would see adult care facilities face crises.

We would see childcare in crisis as well.

And, we would see many other low-pay jobs, literally not having the people coming into the sector to make them function. So we have a real difficulty.

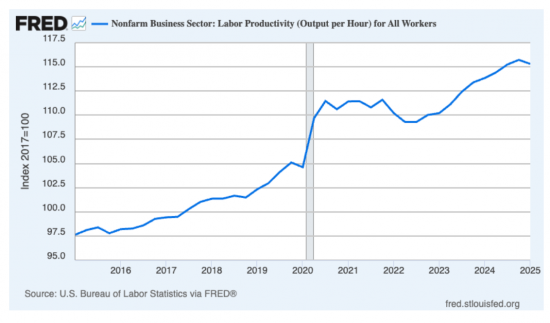

But there’s still an argument to address, and that is one on productivity, because what people claim when they criticise migrant workers and claim that they reduce wages is that the migrant workers who are coming in are reducing productivity inside the labour market.

Paul Krugman addresses this issue very intelligently, which is, I guess, why he ended up with a Nobel Prize. What he says is that we can’t predict how migrants react with the economy until we actually look at who they really are and what skills they have to bring. He suggests that there are four competing effects that we must consider.

The first one is that, actually, there is effectively capital dilution as a consequence of migrant workers coming in. In other words, the amount of labour per quantity of capital inside the economy increases, and therefore, productivity falls.

Now, the fact is, there’s no evidence to support this, largely because capital isn’t a fixed quantity. Capital is continually regenerated within the economy by new investment, and the evidence is that so long as the economy grows, and migration is feeding growth, then investment will keep up with the rates of growth, and therefore, there is no dilution, and therefore, migration is not reducing productivity. So we don’t need to worry about that.

Migrant labour is not substituting for capital investment.

Then there’s a claim that migrants have lower skills and therefore they’re debasing the level of work in the economy, but again, there’s very little evidence to support this. In fact, many migrants come in with very strong skills, but are doing work which is beneath their skill level.

But they’re also doing something else, which is really important because what they’re actually doing by undertaking these more menial tasks, which they tend to end up in, is releasing other people to use the skills they’ve got within the economy, which otherwise they couldn’t do.

For example, carers who are freed up, whether it’s for old-age people who are being cared for or for children who are being cared for, can work in a way that they couldn’t because migrants are looking after those that they love. And that therefore increases the skillset available to the economy.

Third, there’s an issue around complementary skills.

In other words, what those who are coming into the country as economic migrants do actually complements existing skills because they’ve been trained in different ways from those who are already in the UK.

They might well add to our skill set by bringing in different experience, and that is something that we can learn from, and actually, overall productivity rises as a consequence. In other words, migrants don’t drag down the skillset in the UK economy, but it is highly likely that by bringing in their different experiences, they increase the quality of the skillset in the economy.

And finally, there’s a question of motivation. Economic migrants work incredibly hard. Again, I can say this from personal experience.

I know that in my extended family, where it was by and large, the parents or grandparents who came to this country, their work effort was phenomenal. They wanted to integrate. They wanted to ensure that they could provide security for their family. And the fact that they even came here to do that was the consequence of what we might call a selection effect.

The migrants who arrive in the UK are those who are already highly motivated. It takes significant effort to get to this country. It takes a lot of effort to leave your ties behind and move to another place. And as a consequence, many of the people who come to the UK will outperform their locally born peers simply because their motivation level to ‘get on’ is higher than those who are already here, and we shouldn’t ignore that.

We’ve had a surge in migration. There’s no doubt about that. It’s happened in the USA, it’s happened in the UK, and it happened around the same time, and there are strong reasons in international relations why that has happened.

Stress in the rest of the world has created it at present.

Climate change is going to make it a lot worse.

And this trend is going to continue as a consequence, but let’s be clear about it. This is not a threat, as the evidence in the US shows productivity in recent years has risen, not declined, despite having significantly higher rates of legal inward migration.

Migration, therefore, does not create lower productivity. In fact, the evidence in the USA is quite the opposite. GDP is higher in the USA as a consequence of migration, and in the UK, it is at least stable per head of population, which otherwise it might well not be, as a consequence of there being no migrants.

So migrants work.

Migrants pay.

They pay into pensions and they pay into public services, as well as working in them.

They contribute to the social security system, and in the US, there’s strong evidence that that system will collapse without them.

In reality, they’re the people on whom we might well depend for care when we’re elderly or who will be looking after our young.

The UK’s pension system is absolutely desperate for them to be working in this country, because unless they come here and sacrifice part of their income to keep a generation who do not include their parents, in their case, because their parents will be elsewhere, then the elderly will be in deep trouble in the future.

We could reduce migration, but if we did, we would massively increase fiscal pressure as a consequence. We would not reduce it.

The big picture is this: economic necessity and justice demand that we treat migrants fairly.

As do, of course, human rights demand that we do just that. These people are our equals, and in international law, they’ll have a right to be here.

The vast majority of people who migrate to this country come on visas and will be welcomed as a consequence.

Many of those who arrive in small boats will also end up here because they can prove their right to asylum.

A tiny number are actually the reason why there’s a massive anti-migrant hysteria in this country, and it’s almost wholly misplaced.

Migration is not a burden on the UK. It’s the foundation of our future, and for that reason, we need to have a positive acceptance of migration and a discussion about how we can integrate people into this country for our long-term benefit.

Taking further action

If you want to write a letter to your MP on the issues raised in this blog post, there is a ChatGPT prompt to assist you in doing so, with full instructions, here.

One word of warning, though: please ensure you have the correct MP. ChatGPT can get it wrong.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog’s glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog’s daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here: