Twenty or so years ago I was invited to speak at a CEO “boot camp” in New York for a group of newly appointed chief executive officers of big US companies. My remarks on the new media landscape were listened to politely, but the freshly minted chief executives came alive when they were photographed by legendary portraitist Richard Avedon and when they were invited to ask questions of their hero, former General Electric boss Jack Welch, then every CEO’s favourite CEO.

Standing with chest puffed out and one foot up on a chair, the man nicknamed “Neutron Jack” for his mass dismissals showered them with invaluable advice, such as “never put an academic on your board – only have people who are much wealthier than you and won’t get envious as you get richer”.

The boot camp was a sort of initiation for winners of the American Dream, who to a man (on this occasion, literally) exuded a sense of being in charge, empowered and determined to get stuff done. To many ordinary Americans, the power of the big desk in the corner office is a source of inspiration, which helps explain why so many of them voted twice to elect as their president a CEO-in-chief best known for turning his name into a brand, and for firing people.

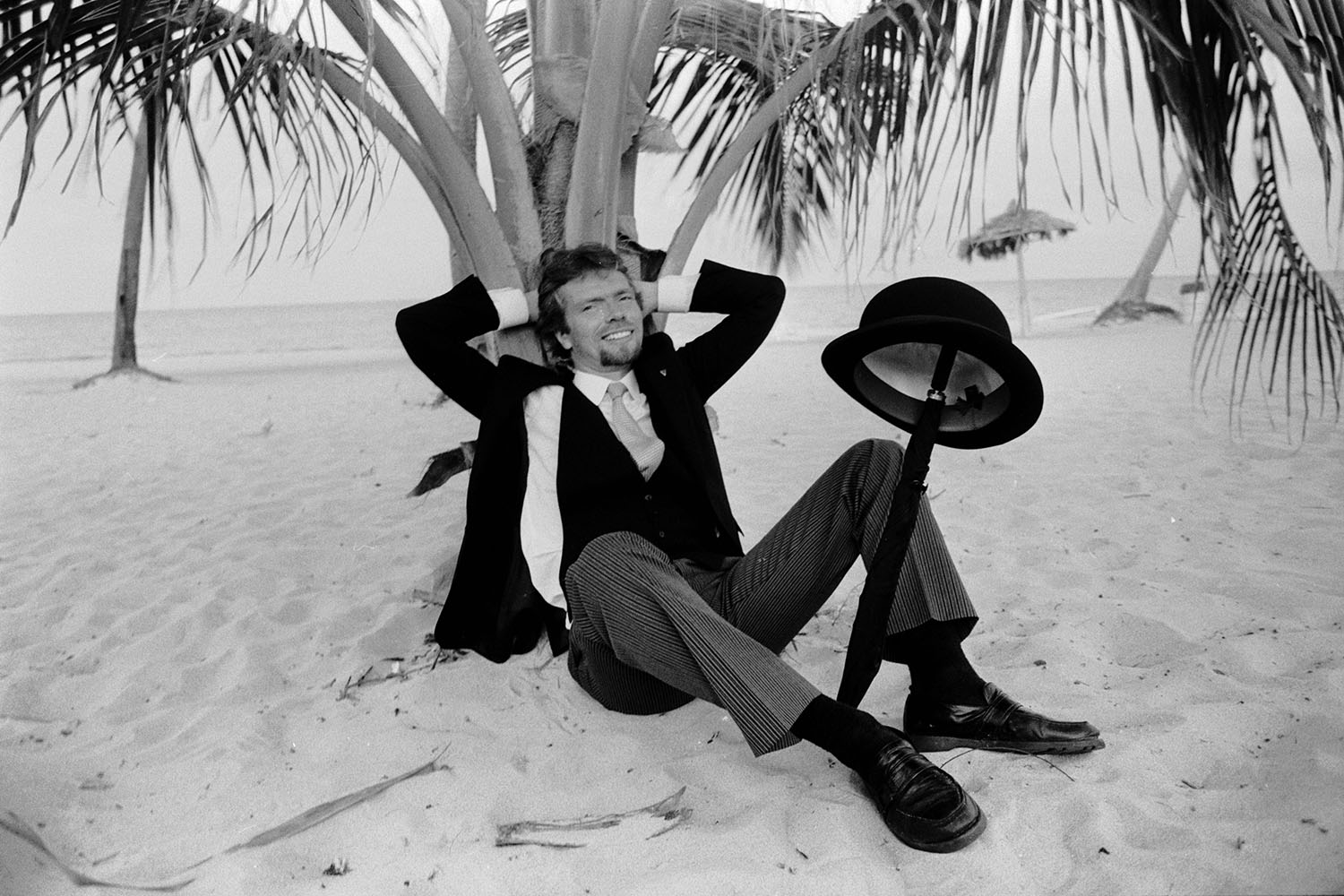

The British have never fully embraced the cult of the CEO, tending to regard captains of industry less as role models than as greedy, crony capitalists. Popular one-offs like Richard Branson or, a century earlier, the tea and provisions magnate Thomas Lipton, the country’s first celebrity boss, are the exceptions who prove the rule.

The term CEO didn’t even catch on here until the late 1970s, more than 60 years after it was first used – in America, of course – by Elbert H Gary of US Steel. Until then, British firms were typically led by a managing director or chairman, who was often seen as part of the problem rather than the solution. As the business historians Michael Aldous and John D Turner note in their fascinating, thought-provoking book, as far back as 1919 the great economist Alfred Marshall observed that the performance of large British firms lagged behind that of their peers in the US and Germany, attributing this to their managers being amateurs.

In the 1960s, technocratic Labour prime minister Harold Wilson complained that British industry was still run by people with aristocratic connections or inherited wealth and that we were “content to remain a nation of gentlemen in a world of players”. Yet, Aldous and Turner conclude, the “gradual professionalisation of British corporate leaders has not proved to be the panacea that Alfred Marshall and many others sought for Britain’s poorly run companies”. Instead, we have ended up in an era of “exorbitant pay, super-rich CEOs, and hubristic captains of industry”.

To understand how this came to be, Aldous and Turner have built a database of the nearly 1,400 bosses of firms that have featured at any time since 1900 in the top 100 most valuable British companies on the London Stock Exchange. They illustrate their number crunching with colourful stories about several eras’ worth of British corporate chieftains, from the Earl of Rosebery to Martin Sorrell. Notwithstanding the overall message of the book, many of these tales are positive, including some remarkable contributions to the British economy by the likes of Lipton, Unilever founder William Lever, shipping tycoon John Ellerman, corporate raider James Goldsmith and, before a scandal cost him the CEO job at advertising firm WPP, Sorrell himself.

The amateur-aristocratic era may not have been as bad as it has been painted, Aldous and Turner find. Yes, in the first decade of the 20th century, 41% of those in what we now call CEO roles were peers of the realm. Yet there was no meaningful difference in profitability and stock-market valuations between firms run by so-called gentlemen and those from non-privileged backgrounds. And Britain’s productivity and economic growth until 1920 still compared favourably with America’s.

Harold Wilson complained we were ‘content to remain a nation of gentlemen in a world of players’

Relative performance only started to deteriorate significantly after 1950, when Britain bungled its embrace of the managerial revolution taking place across the Atlantic. While big US companies were being populated by graduates of the nation’s business schools (the UK didn’t get its first proper one, London Business School, until 1964), British firms promoted lots of narrowly educated engineers and accountants, when what bosses really needed at the start of the age of consumerism was sales and marketing expertise. Wilson made matters worse by encouraging a wave of mergers to create industrial national champions, which were then poorly managed by the wrong sort of CEOs.

In the 1970s, buccaneering bosses like Goldsmith and James Hanson restored financial discipline by pursuing hostile takeovers of badly run firms, albeit often at the price of cutting long-term investment, while the privatisations of state-run businesses in the 80s and 90s may have improved productivity but, as their remuneration soared, also turned CEOs into overpaid “fat cats”.

Since then, CEO pay has continued hurtling towards US levels, increasingly rewarding short-term risk-taking that, despite some individual successes, in aggregate has failed to improve Britain’s economic underperformance. Look at bankers like former RBS CEO Fred “the Shred” Goodwin, whose own highly paid recklessness helped precipitate a financial crisis. Today’s targets of complaints about excessive pay include Ken Murphy, CEO of Tesco, whose £9.9m total remuneration last year was 430 times that of the average Tesco employee.

Aldous and Turner attribute this above all to a profound failure of corporate governance that gives CEOs the wrong incentives and does not hold them properly to account. They propose several fixes, none of them entirely straightforward, including requiring companies to have a stated social purpose; legal obligations to take into account the interests of employees and the wider society as well as investors; subjecting companies to more vigorous competition policy; and tying CEO pay to that of the average worker in the firm.

Neutron Jack would not approve.

The CEO: The Rise and Fall of Britain’s Captains of Industry by John D Turner and Michael Aldous is published by Cambridge University Press (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

Photograph of Richard Branson in 1986, courtesy of Getty Images