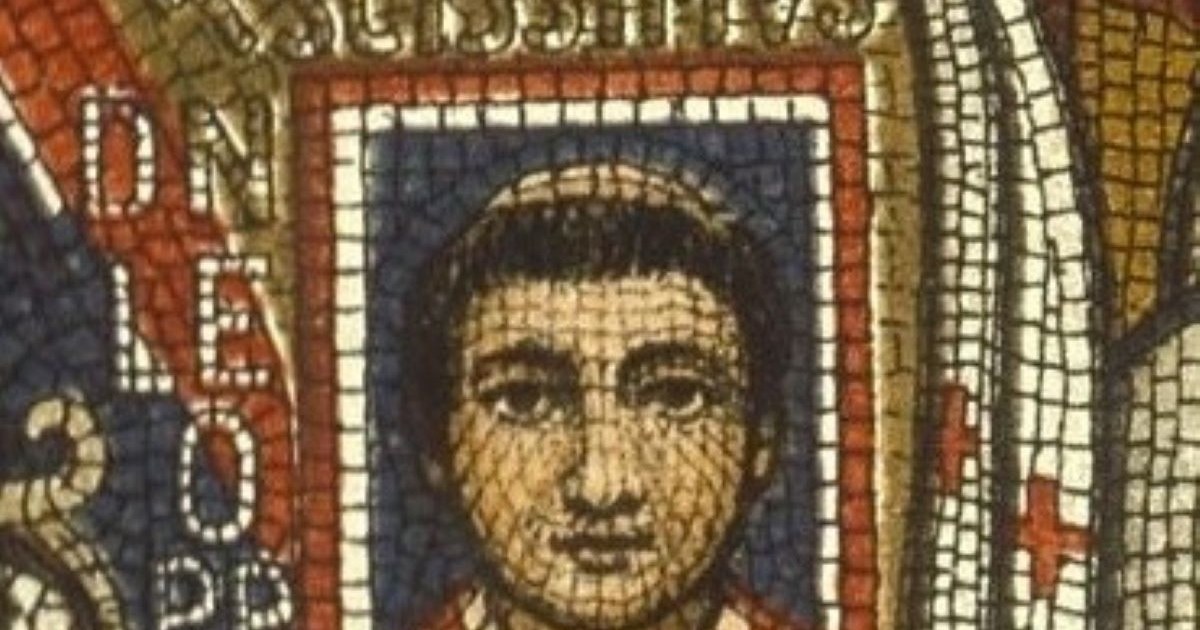

One of the oldest representations of Pope St. Leo III can be found on the mosaic of the Triclinium Leoninum. This monument is the remnant of an opulent banquet hall that the pontiff had built during his long pontificate (795-816) near the Basilica of St. John Lateran. Leo III is depicted there with Charlemagne at the feet of St. Peter.

The leader of the apostles hands them the insignia of their respective authority, emphasizing the equal distribution of religious and political power between the two men. In the same mosaic, the presence of Emperor Constantine receiving his insignia from Christ emphasizes the religious nature of imperial authority. This is a way of recalling that Leo III was the only one who could crown an emperor, which he did in 800 when he crowned Charlemagne.

The Triclinium Leoninum in Rome. On the right, Leo and Charlemagne kneel at the feet of St. Peter.

The Triclinium Leoninum in Rome. On the right, Leo and Charlemagne kneel at the feet of St. Peter.Wikicommons/LPLT

Humble origins

Little is known about the early life of Leo III, except that the Liber Pontificalis emphasizes his modest ancestry. Without fortune or support among the great Roman families who then controlled Rome, this priest—trained at the Lateran—probably owed his rise to his particular attention to the clergy.

Leo III’s predecessor, the powerful and wealthy Adrian I, had obtained from Charlemagne, victor over the Lombards, the creation of the “Patrimony of St. Peter” – the beginnings of the Papal States. When he died in 795, Leo was elected pope. Politically isolated, his first public act was to send the banner of Rome and the keys to St. Peter’s tomb to the king of the Franks, thus officially recognizing him as “defender of the faith.”

At first, Charlemagne did not seem to attach much importance to Pope Leo III. Things changed when, in 799, Leo III narrowly escaped an assassination attempt orchestrated by his predecessor’s nephew and was forced to flee Rome. Charlemagne, advised by his counselor, the theologian Alcuin, decided to come to his rescue.

After a trial in which the king acknowledged that a pope could not be judged, the attackers were exiled and the Roman nobles had to recognize Leo III as the undisputed religious authority.

The crowning of Charlemagne

It was in this context that Charlemagne was crowned by Leo III in St. Peter’s Basilica in 800. The Frankish king took advantage of the fact that the throne of Constantinople was then occupied – illegitimately, according to his theologians – by a woman, Empress Irene.

It’s not known exactly who was behind the coronation, but all the players, whether the Franks, the Romans, or the papacy, seem to have emerged as winners.

Rome thus regained its imperial status, Leo III’s Church presented itself as the only authority capable of legitimizing this power, and the new emperor strengthened the theocratic role of his government.

Under Carolingian rule, the pope further accentuated Rome’s separation from Constantinople. The council held in Aachen in 809 declared for the first time that the Latin version of the Creed – with the controversial filioque clause – was the only valid one. Leo III, although opposed to this view, was forced to accept it. He died in 816, two years after Charlemagne.