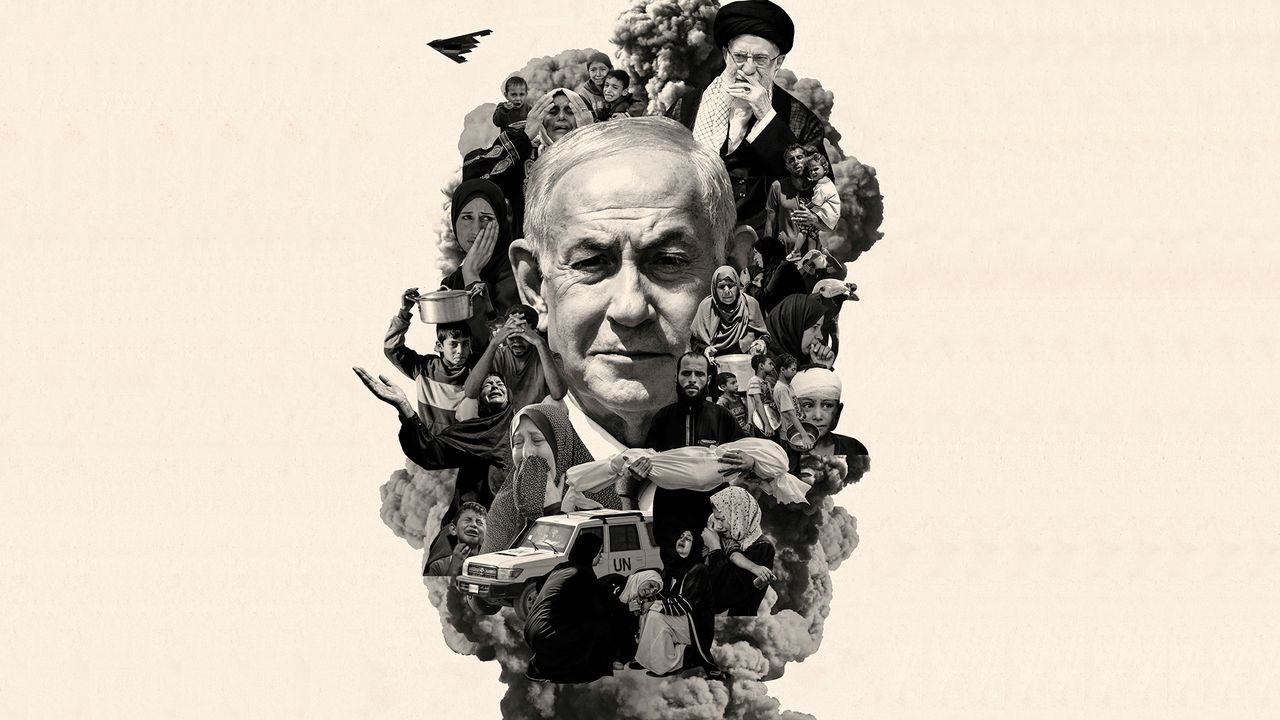

“What we are doing in Gaza now is a war of devastation: indiscriminate, limitless, cruel and criminal killing of civilians,” Ehud Olmert, a former Prime Minister, wrote in Haaretz. He said that his country was guilty of war crimes. “We’re not doing this due to loss of control in any specific sector, not due to some disproportionate outburst by some soldiers in some unit. Rather, it’s the result of government policy—knowingly, evilly, maliciously, irresponsibly dictated.”

Hamas launched its October 7th attack with the knowledge that it would provoke an immense Israeli reprisal. To regain control of historical Palestine for the Palestinians and to eliminate the Zionist state, Sinwar once remarked, “we are ready to sacrifice twenty thousand, thirty thousand, a hundred thousand.” He knew that the war could bring horrifying casualties; he had helped construct, with Iranian and Qatari money and the cynical complicity of the Israeli government, a militarized landscape of tunnels and outposts embedded in schools, homes, hospitals, and U.N. sites. The suffering of Palestinian civilians wasn’t merely a foreseeable consequence; it was an integral part of the strategy. It is only faintly remembered now, but in the immediate aftermath of October 7th Joe Biden not only threw his arms around Israel but also counselled its leadership not to act out of “an all-consuming rage.” On the nightly news, Israelis have scarcely seen the ruins, the atrocities, the outcome of that rage as it has been unleashed for nearly two years.

“Everyone believes in the atrocities of the enemy and disbelieves in those of his own side, without ever bothering to examine the evidence,” George Orwell wrote after fighting on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. “Unfortunately the truth about atrocities is far worse than that they are lied about and made into propaganda. The truth is that they happen.”

Before October 7th, Netanyahu, like much of the Israeli security establishment, regarded Hamas as a problem to be managed, not as an existential threat. A nuclear Iran was the obsession: the shadow on the wall. For more than half a century, Israel has been the region’s only nuclear power. This reality underpins Israel’s doctrine of deterrence, and its deepest anxieties. It has kept Iran at the top of every Prime Minister’s agenda, no matter how many rockets fell from Gaza. Iran covets what Israel has; Israel fears what Iran could build. The irony is that Israel’s nuclear advantage began with a different kind of crisis entirely.

In 1956, after Egypt’s President, Gamal Abdel Nasser, nationalized the Suez Canal—ousting the British and French as colonizers—the evicted powers asked Israel to invade Sinai. Britain and France were looking for an excuse to intervene as “peacekeepers” and regain control of the canal. Shimon Peres, then director general of Israel’s Ministry of Defense—and decades later a Nobel laureate for his role in the Oslo Accords—helped hammer out the deal: in return for Israel’s part in the operation, France agreed to supply nuclear technology.

The Sinai campaign was a disaster, but the French Prime Minister, Guy Mollet, kept his side of the bargain. “I owe the bomb to them,” he said. The Israelis soon established a nuclear program at Dimona, a village in the Negev. In a bit of global fakery, David Ben-Gurion claimed that the reactor was for desalination, to make the desert bloom. President John F. Kennedy was unconvinced, and alarmed by the prospect of nuclear weapons in the Middle East. But, after Kennedy’s assassination, American opposition subsided. Today, Israel has a substantial stockpile of nuclear bombs but does not acknowledge it. Instead, Israeli officials maintain a policy of amimut, or strategic ambiguity. Recently, I was interviewing a retired leader of one of the intelligence agencies. After he described the power of Israel’s arms and its ability to cope with its adversaries, he added, with a thin smile, “And, of course, we possess, according to foreign sources, other strategic advantages.” “According to foreign sources”: that’s always the phrase.

At the same time, Israel—which has been threatened since its inception—has taken pains to deny its adversaries such “strategic advantages,” backing vigilance with force. In 1980, Menachem Begin and his intelligence services had to reckon with the fact that the Iraqi President, Saddam Hussein, was building Osirak, a reactor in an isolated outpost near Baghdad. For Begin, whose father, mother, and brother were murdered by Nazis, this augured a second Shoah. He told his military chiefs, “This morning, when I saw Jewish children playing outside, I decided: No, never again.” Despite the ardent warnings and objections of Peres and other officials in his government, Begin won support in the Cabinet and, in June, 1981, dispatched eight U.S.-made fighter jets to drop sixteen bombs on the Osirak reactor. Israel was condemned in the United Nations, including by the United States.

Begin, ordinarily protective of Israel’s relationship with its American patron, believed that he was duty bound to strike Iraq. In a letter to President Ronald Reagan, he wrote, “A million and a half children were killed by Zyklon B gas during the Holocaust. This time, it was Israeli children who were about to be poisoned by radioactivity.” The attack on Osirak became the foundation of the Begin doctrine, which held that no adversary in the region would be permitted to obtain a nuclear weapon. If one tried, Israel would act.

In 2007, Mossad agents broke into the Vienna apartment of Ibrahim Othman, the head of the Syrian Atomic Energy Commission. According to a comprehensive account by David Makovsky in The New Yorker, the agents extracted conclusive evidence from Othman’s computer: Syria was secretly building a plutonium reactor, Al Kibar, with help from North Korea. The Mossad chief, Meir Dagan, brought the findings to Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, who decided to attack before the reactor went “hot,” lest radiation leak into the Euphrates.

The Israelis were eager for American backing, but the George W. Bush Administration, still reeling from the debacle in Iraq, was hesitant. “Every Administration gets one preëmptive war against a Muslim country,” Robert Gates, the Secretary of Defense, told an aide, “and this Administration has already had one.” Condoleezza Rice and other senior officials, mindful of Israel’s faltering war against Hezbollah in Lebanon, worried that an Israeli strike would spark an even wider conflict. Meanwhile, Israeli officials looked back at failed global efforts to stop North Korea and Pakistan from acquiring nuclear weapons as a matter of “too early, too early—oops—too late.” They were convinced that they couldn’t afford to wait. The signals between Bush and Olmert were purposefully vague. Olmert didn’t ask for a green light, and Bush didn’t give one—but he didn’t flash red, either.

Around midnight on September 5, 2007, eight Israeli jets crossed into Syria and dropped seventeen tons of explosives on Al Kibar. Syrian state media claimed that the aircraft had been confronted and driven off, “after they dropped some ammunition in deserted areas without causing any human or material damage.” Once the jets had landed safely, Olmert called Bush and said, “I just want to report to you that something that existed doesn’t exist anymore.” In the weeks that followed, Bashar al-Assad denied that Israel had struck anything of consequence in Syria. The Israelis, for their part, maintained their silence. This “zone of denial,” as security officials called it, allowed Assad to avoid public humiliation and kept him from retaliating.

Netanyahu has been warning about an Iranian bomb since 1992. Back then, as a young Likud member, he told the Knesset that Iran would have the capacity to build a nuclear weapon “within three to five years.” Since then—in speeches to the United Nations and Congress, in books, in Cabinet meetings—he has sounded the alarm about nuclear imminence at every opportunity.

There are many reasons to distrust Netanyahu: his habitual lying; his willingness to prop up his coalition with religious zealots and racists; his brutal, protracted prosecution of the war in Gaza, a strategy that seems motivated in no small measure by a desire to cling to power. It seems clear that he has sometimes exaggerated the speed of Iran’s progress toward becoming a nuclear-threshold state. But the reality of Iran’s ambitions can’t be dismissed. Iran has repeatedly called on its own scientists and turned to the network of Abdul Qadeer Khan, the father of Pakistan’s atom bomb, for help. It has systematically flouted international inspections, and developed a far more sophisticated, dispersed, and hardened program than Saddam Hussein or Assad ever managed—learning from the Israeli strikes on Osirak and Al Kibar and making a single knockout blow nearly impossible.

“I would have thought the tinfoil hats would have kept me from hurting your feelings.”

Cartoon by Frank Cotham

Israel’s anxieties cannot be easily dismissed, either. It is, after all, rare for one member state of the United Nations to threaten another with elimination. I was present at a New York press breakfast of bagels and lox that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad hosted in 2006, at which he described Israel as a “fabrication,” a passing disturbance that would be “eliminated” in due course. In less decorous settings, Ahmadinejad said that the Holocaust was a “myth” and that Israel should “vanish from the page of time.” A previous Iranian President, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, judged that Israel was small enough to be “a one-bomb country.” In September, 2015, Khamenei was clear: “Israel will not exist in twenty-five years.” A few years later, the regime installed a digital clock in Tehran’s Palestine Square, counting down the days to 2040 and the anticipated victory over Israel.