Around the world, sharply opposing views on juvenile justice are emerging and understanding them is crucial if Australia is to head in the right direction, writes Gerry Georgatos.

NORWAY’S JUVENILE JUSTICE system is widely regarded as one of the most progressive and formidable rights‑based frameworks in the world. It is fundamentally shaped by the nation’s deep commitment to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and its broader social democratic welfare model. These foundations position young people not as objects of state control but as firmly active stakeholders whose rights, needs and potential are central to justice processes. They go to the heart of validation.

Norway has embedded the principles of the CRC, which emphasise the authentic best interests of the child, the right to participate in decisions affecting their lives independently, and the importance of proportionality in justice responses, across its justice, education and welfare systems. This inclusive rights‑based approach exists within a broader social justice paradigm that guarantees universal access to health care, education, mental health support and child welfare services, reflecting the view that childhood wellbeing is a collective responsibility.

Scholars examining the Norwegian model note that it seeks not simply to react to crime but to build the conditions for young people to flourish, thereby reducing the likelihood of offending.

At the heart of Norway’s juvenile justice system lies a strong commitment to rehabilitation and restoration rather than punishment, to transformation. The minimum age of criminal responsibility is set at 15 years, ensuring that children younger than this are dealt with through child welfare systems rather than the criminal courts. In the USA, the minimum age varies across the 50 states, with as low as eight and at best as high as 12, with one state recently as low as six years of age.

In Norway, for those aged 15 to 17, the response to offending behaviours is primarily non‑custodial and restorative. Two key sanctions dominate the framework: the Ungdomsstraff, or Youth Penalty, and the Ungdomsoppfølging, or Youth Follow‑Up.

The Youth Penalty was introduced in 2014 as a comprehensive sanction for serious juvenile offending. It couples restorative conferencing, often conducted through Norway’s mediation boards known as Konfliktrådet, with an individualised follow‑up plan that includes education, family support, therapy and close supervision by youth coordinators. For less serious offending, Youth Follow‑Up provides structured oversight focused on school attendance, counselling and parental engagement, again prioritising rehabilitation over incarceration.

The Konfliktrådet play a pivotal role in ensuring that restorative practices are embedded in Norway’s juvenile justice response. These community‑based mediation boards bring together victims, offenders, families and other stakeholders in a dialogue designed to repair harm, foster accountability and reach agreement on meaningful outcomes. Norway also utilises Barnahus, or children’s houses, as specialised facilities that provide a safe, child‑friendly environment for forensic interviews, medical examinations and coordination between welfare and justice agencies.

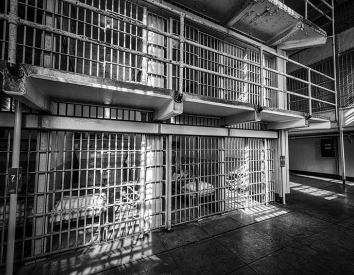

This model minimises the trauma of repeated questioning and intimidating institutional settings, allowing children to participate more fully in processes affecting them (Barnahus model). Even when detention is necessary, Norway adheres to the normality principle, under which deprivation of liberty is the only punishment and all other rights and privileges are maintained as far as possible. Detention is rare, short and designed to mirror normal life conditions to maximise the prospect of reintegration.

Although Norway’s juvenile justice model is internationally acclaimed, it has faced challenges in recent years, particularly in Oslo. Since around 2016, the capital has experienced an uptick in youth crime, including gang recruitment, violent incidents and drug‑related offences. In 2024 and 2025, overall youth crime rates began to plateau, yet the proportion of violent and hate‑related offences remained troubling. Reports revealed that in 2024, nearly 7,700 youth crime incidents were recorded in Oslo, with concentrated spikes in marginalised urban districts.

These developments prompted renewed calls for strengthened early‑intervention strategies, particularly for children in immigrant and low‑income communities who are at heightened risk of exclusion. Norway’s national Auditor and the Children’s Ombudsman criticised the insufficient scale of preventive programming and urged the government to expand services in vulnerable neighbourhoods.

In response, Norway introduced a series of measured reforms between mid‑2024 and 2025. These reforms granted courts greater discretion to impose up to six months of unconditional detention in the most serious juvenile cases, introduced electronic monitoring for compliance where necessary and established fast‑track youth courts to expedite proceedings. The requirement that young people and their guardians consent to the enforcement of youth sentences was removed, though their rights to appeal and participate in decision‑making were reinforced.

These changes were controversial in some quarters, with concerns that they risked eroding the rehabilitative ethos of the system, yet the reforms were carefully circumscribed and accompanied by safeguards designed to prevent an overly punitive drift. I am not arguing whether I agree with these or not; rather, I am describing.

However, when compared with the United States’ “tough on crime” approach, the contrast could not be starker. The U.S. remains one of only two countries in the world that have not ratified the CRC (U.S. State Department) and maintains a fragmented juvenile justice framework that varies significantly between states. Many states have no minimum age of criminal responsibility, and those that do may set it or have set it as low as six, and currently as eight or ten years old.

The United States is also the only nation in the world that still sentences children to life imprisonment without parole. Detention is common, and conditions are frequently harsh and adult‑like, as demonstrated by studies of youth held in adult correctional settings. Restorative justice initiatives remain peripheral rather than central, with pilot programs existing in scattered jurisdictions but rarely integrated into mainstream juvenile justice systems.

The Norwegian model demonstrates that a justice system can hold young people accountable for harmful behaviour while still prioritising their long‑term development and reintegration. The system is deeply inter‑sectoral, integrating the work of child welfare, mental health, education and community organisations. Preventive efforts begin early, through universal services and targeted programs addressing poverty, social exclusion and the structural drivers of crime.

Children’s rights to be heard, to maintain relationships with family and community, and to access support are integral, not optional. This holistic design helps to explain Norway’s exceptionally low rates of juvenile incarceration and recidivism.

The Norwegian experience also illustrates that maintaining a rehabilitative system requires constant vigilance. Rising youth crime in Oslo and elsewhere has generated political and public pressure to become more punitive. The challenge for Norway will be to expand restorative infrastructure in marginalised communities, ensuring that mediation boards and school‑based restorative initiatives reach those most at risk of exclusion.

There is a pressing need to monitor the impact of new enforcement measures, such as electronic monitoring and extended detention, to ensure they do not undermine the rehabilitative heart of the system. Independent evaluations, led by child rights institutions, will be essential in safeguarding against mission drift.

For the United States, the lessons are clear and urgent. Ratifying the CRC and adopting a coherent rights‑based juvenile justice code would provide a framework for setting a sensible minimum age of criminal responsibility, abolishing life sentences for juveniles and placing non‑custodial, restorative measures at the centre of the system.

Developing child‑friendly facilities that are modelled on Norway’s Barnahus would reduce trauma for children who are victims, witnesses or accused. Investing in upstream interventions that address poverty, mental health needs and educational engagement would prevent many children from entering the justice system at all.

Norway’s juvenile justice system shows that another way is possible: one in which accountability is not synonymous with punishment, and where the dignity and potential of every child is recognised. Even as Norway navigates contemporary challenges in Oslo and elsewhere, its model continues to offer a powerful example of how to balance public safety with social justice.

The United States, by moving away from punitive practices and embracing a rights‑based, rehabilitative philosophy, could similarly offer its young people not a lifetime defined by mistakes but the opportunity to repair harm, rebuild lives and contribute meaningfully to their communities.

Australia has 17 juvenile prisons and 115 adult prisons. On current trends, Australian prisons will at least double by 2040. Australia can continue to follow the dead-end, one-way street of the USA or go the way of Norway.

Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher with an experiential focus on social justice.

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles