In my recent post that included Federal Reserve political independence, I dared to use the word ‘trust’, and commenters let me know that they were not pleased about it. In strict economic terms, there is no such thing as trust. Either that, or it’s the same thing as expectations or maybe low-information expectations. Since it wasn’t the main thrust of my post, I didn’t lay-out the informed reasoning behind my confidence in President Trump’s inability to cause Argentina or Turkey or even 1970’s US levels of political influence on the Fed.

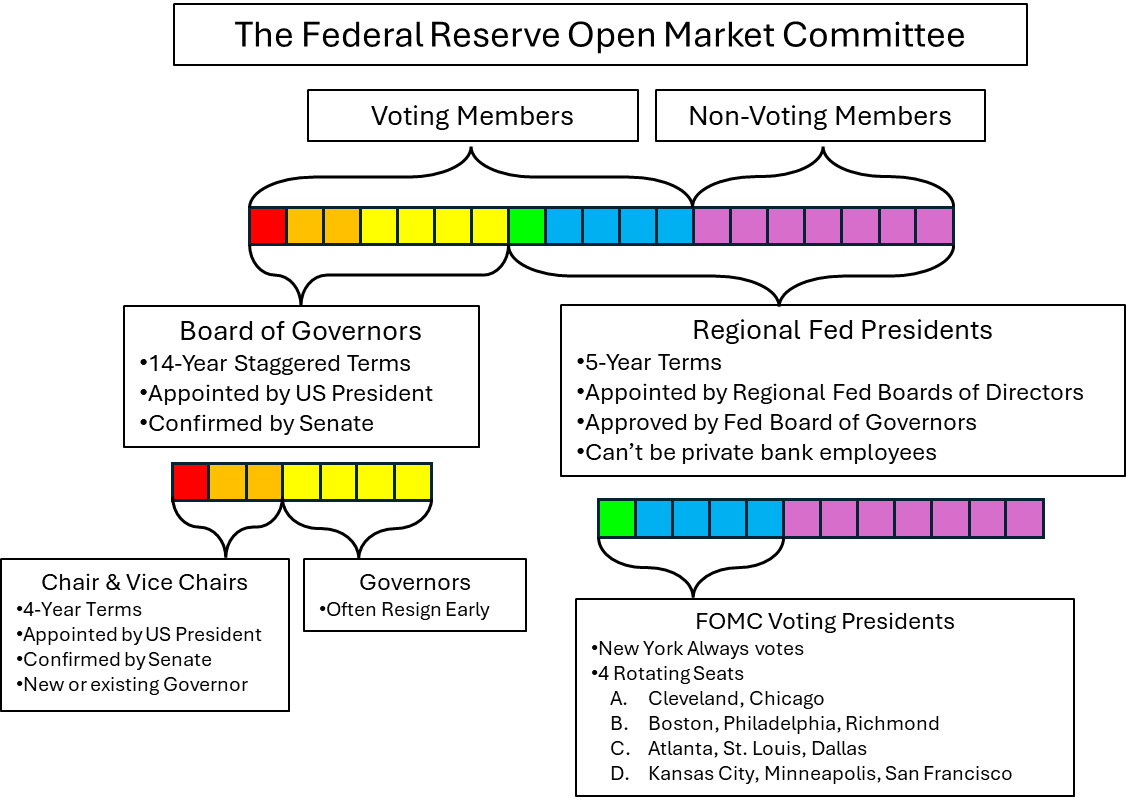

In short, I’m not worried about it because the operational structure of the Fed and the means by which individuals join the Fed are determined by congress and are pretty good robust. Below is a diagram that I made. I know that it’s a lot, but I’ll explain below.

There are 19 members of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC). Of those members, 12 vote on interest rate policy. Of the voting members, 7 are always the Board of Governors (BOG). The other 5 voting members are presidents from the 12 Federal Reserve Regional Banks. All Regional Fed presidents are members of the FOMC.

All of the BOG members are nominated by the US president and confirmed by the US senate for 14-year staggered terms. They can serve consecutive terms and governors typically resign before serving all 14 years. Two of those members are the vice chairs, nominated by the US president and confirmed by the US senate again. Finally, 1 of the BOG members is the chair, nominated and confirmed again. The chairs and vice chairs all serve 4-year terms.

If governors served their full term, then a two-term president could choose a maximum of 4 governors by the time they leave office. But governors often depart early for a variety of personal and career reasons. One of those reasons can be political insofar as they know which president will choose their replacement. So they may adjust their departure date. Obama appointed 5 governors, Trump I appointed 2, Biden 4. It’s hard to say, but that pattern may be luck, or politically timed resignations. Even if Trump appoints a new Chair, that’s 3 of the 7 governors that he’ll have appointed. That’s 3 of the 12 voting members. The overall scheme allows governors to offset extreme policy desired by the US president.

First, I’ll describe FOMC voting regional Fed presidents, then some details about all regional Fed presidents. First, 1 of the 5 voting presidents is always from the New York Fed given that it’s a major hub of banking and finance. The other four fill seats that serve rotating 1-year voting terms, organized by geographic group. So, the Cleveland and Chicago presidents take turns as voters. Similarly, the Atlanta, St. Louis, and Dallas presidents take 1-year turns. This design ensures that the various geographic areas of the US are represented. There’s never a year when all of the governors happen to be from the east coast or happen to be from the south.

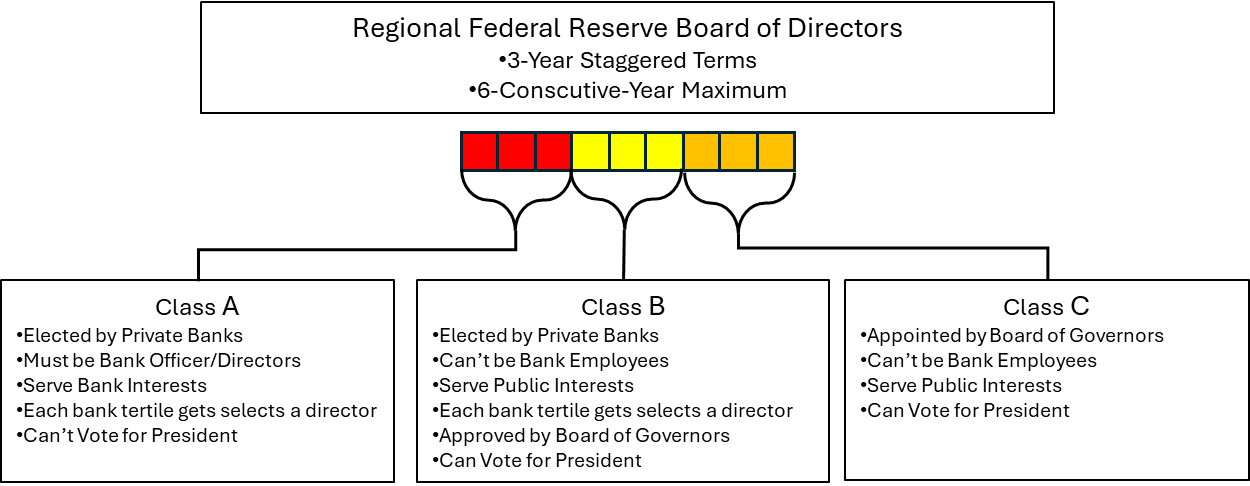

But how does a regional Fed president get selected in the first place? By their regional Fed Board of Directors (BOD). Time for another diagram.

Each of the 12 regional Feds has a separate 9-member BOD. The BOD is composed of 3 equally represented director classes (A, B, & C) that are chosen differently. All directors serve 3-year staggered terms. The three Class A directors are elected by private Fed-regulated banks to serve private bank interests. These directors must be officers or directors from the regional private banks. Class A directors can’t vote for the regional Fed president.

Class B is also elected by banks, but directors can’t be bank employees and they must ‘serve the public interest’. In practice, this means that they must credibly represent industry, agriculture, labor, or consumers. Class B directors are approved by the BOG, which is very sensitive to the purpose of these seats and avoiding Bank interest. Both Class A & B directors are elected by banks that are split into tertiles. So, there is 1 Class A & B seat for each big, medium, and small bank voters.

Finally, Class C directors can’t be bank employees and are selected by the BOG. They also must ‘serve public interest’. This is the least ‘bank-y’ class. Only Class B & C directors can vote for the regional Fed president, who serves 5-year terms. The president can’t be a member of the BOD.

The structure of Regional Fed BODs is such that a diversity of banks choose different directors who serve each bank and public interest. While the BOG must approve Class B directors, the BOG can only outright appoint Class C directors. This means that a minority of the FOMC, the governors, chooses a minority of each regional BOD. And, directors chosen by private banks and the BOG have equal say in who the regional Fed president will be.

It seems like the BOG has a lot of influence. But, the influence over regional presidents is diluted by private banks. Further, the US president’s influence over the BOG is severely limited by when the governor terms expire or when they step down – not to mention the US senate’s approval. Given that most interest rate decisions are near unanimous, a single extreme FOMC chair can’t hugely sway fellow FOMC voters. Similarly, a single Chair can’t exert huge sway over director Class B approvals or Class C appointments.

The Federal Reserve System attempts to mimic the balance of powers that is present in our three branches of federal government, and the unique short and long-term interests are analogous to the US legislature. The 20th century progressive twist is that private banking industry is involved too. My overall point is that the president can try to influence the Fed. But, despite its name, the Fed is not a single entity. It’s a diversity of roles, interests, horizons, voters, and geographies. I trust any one of those involved to pursue their own broadly construed self-interest. This is not the kind of blind trust in an idea, or the faithful trust of a social relationship. This is a trust that is built into the axiomatic foundation that underlies all economic analysis.

For these reasons, I’m not worried about Trumps’s influence on the Federal Reserve. While it’s true that the rules could possibly change, no one has suggested practical or detailed means by which it would realistically occur.