Beliefs are defined as claims or ideas about “reality that are not based on evidence, but are instead based on value systems, loyalties, reference groups, social institutions, elite opinions, and ideological predispositions” (Hindman, 2012, pp 589–590). Beliefs are unfalsifiable statements that are formed based on one’s supposition or wishful thinking, meaning that any belief may or may not be true and there is no consensus about a correct answer upon which to make a judgment (Veenstra, Hossain, & Lyons, 2014). Given that individuals’ beliefs play important roles in influencing attitude formation and social and political behaviors (Allport, 1954), a body of research has examined how citizens form their beliefs about race (Dixon & Linz, 2000), scientific issues (Hindman, 2009), and politics (Hindman, 2012), among other topics.

Numerous studies have focused on how the mass media portray certain groups (e.g., African Americans and immigrants) and how exposure to such media may influence individuals’ beliefs or perceptions of these groups (e.g., Dixon & Linz, 2000; Mutz & Goldman, 2010). Founded as an immigrant nation composed of citizens of different races, ethnicities, and religious views, the United States has repeatedly confronted issues resulting from the diverse beliefs of its citizens (Dixon & Linz, 2000). For example, African Americans are often related in the media to criminality; research has indicated that exposure to such coverage activates racially charged beliefs among media users (Dixon, 2008; Dixon & Linz, 2000).

The belief gap hypothesis posits that political ideology plays a stronger role than education in predicting the distribution of beliefs regarding contested issues (Hindman, 2009). The belief gap framework is an extension of the knowledge gap hypothesis, which addresses disparities in knowledge among higher and lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups resulting from information disseminated by mass media (Tichenor, Donohue, & Olien, 1970). Disparities in knowledge acquisition between SES groups occur because higher SES individuals (e.g., highly educated people) tend to acquire and process information from mass media at faster rates (Tichenor et al., 1970; Wei & Hindman, 2011). While the literature on the knowledge gap hypothesis has focused on gaps between information haves and have-nots, especially SES indicators such as levels of education, the belief gap hypothesis takes into account individuals’ political ideologies, which may cause disparities in political beliefs and opinions. Hindman (2009) proposed that citizens’ political ideologies, operationalized as self-identification on the liberal-conservative spectrum, would play an important role in the distribution of politically disputed beliefs. For example, he found a significant association between ideology and beliefs about global warming; specifically, liberals were more likely to believe that there is solid evidence of human-caused climate change than conservatives.

Veenstra et al. (2014) also provided evidence of the role of political identity (i.e., ideology and party identification) in the development of belief gaps about politically contested issues including science-related issues (e.g., climate change and the relationship between vaccinations and autism) and claims about U.S. President Barack Obama. For example, conservatives and Republicans were more likely to have negative beliefs about Obama (e.g., “President Obama wants to take away Americans’ right to own guns” and “President Obama is a socialist”) than liberals and Democrats. These studies suggest that individuals’ political ideologies play an important role in the formation and distribution of disputed beliefs about contested issues and politics. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Political orientations (i.e., ideology and partisanship) are predictors of individuals’ beliefs related to candidates in line with the individuals’ political orientations.

Social categorization process

The social categorization process explains how and why individuals’ political orientations may play a key role in the formation of biased beliefs. Beliefs can be activated and formed through a categorization process in which individuals positively perceive themselves as members of an ingroup and have negative perceptions of outgroup members (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Social categorization, the psychological classification of people into ingroups and outgroups, provides a theoretical mechanism for how people differently perceive ingroup and outgroup members, depending, for example, on whether ingroup or outgroup members perform socially desirable or undesirable behaviors (Maass, Salvi, Arcuri, & Semin, 1989). People tend to have more positive views of ingroup members than outgroup members and are more trusting of ingroup members than members of other groups (Otten & Moskowitz, 2000). In addition, researchers have used the social identity theory to account for the link between partisan media use and polarization. Partisan media use reinforces political group identity by activating positive evaluations of the ingroup and negative evaluations of the outgroup, which in turn leads to greater political polarization (Garrett et al., 2014).

Taken together, the literature indicates that political ideology or partisanship can be used to identify ingroup versus outgroup categorization when it comes to evaluating political matters, including political attitudes and beliefs about political candidates. In other words, the ingroup and outgroup categorization process makes people more likely to accept the views that support their political orientation and more likely to reject the views that are in opposition to their political orientation.

Partisan media use, beliefs, and voting intention

People seek out information that accords with their preexisting predispositions based on their political ideologies and partisan views (Garrett, 2009). Exposure to politically slanted media raises important questions in democracies because of its possible effects on citizens’ political attitudes and behaviors (Sunstein, 2007). For this reason, recent studies have begun examining the consequences of citizens’ partisan media use, finding associations between exposure to likeminded information and more polarized attitudes and political participation (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2012; Stroud, 2011).

Although prior studies have examined the relationship between partisan media use and attitudes toward candidates or attitudinal polarization (Garrett et al., 2014), researchers have given little attention to the consequences of partisan media use on individuals’ beliefs. There’s even less research on how partisan media use influences citizens’ beliefs associated with candidates’ demographic characteristics. Only one previous study has suggested that politically slanted media use is associated with people’s political beliefs about candidates’ race (i.e., Barack Obama’s race) and age (i.e., John McCain’s advanced age; (Kim, 2017). The study found that conservatives who consume conservative media tend to perceive that the United States is not ready to elect a Black president and that McCain is not too old to be president, while liberals consuming liberal media more often are more likely to believe that McCain is too old to be president. However, this study focused on the mediating role of such beliefs and individuals’ knowledge in the relationship between politically likeminded media use and political participation and did not examine how political beliefs would be associated with citizens’ voting behaviors. In addition, other than individuals’ beliefs related to race and age, researchers have not explored whether and how selective exposure can be associated with gender-related beliefs. To fill this gap and add to the literature on the consequences of partisan media use, this study examines the relationship between partisan media use and political beliefs, and further how such gender-related beliefs influence individuals’ voting intention.

Partisan news outlets report political news and information in favor of conservative or liberal perspectives depending on their political orientation, reinforcing the political views of their audience (Jamieson & Cappella, 2008). Partisan media have led citizens to support partisan policies and candidates (Stroud, 2011). Different patterns of partisan media use are known to influence different beliefs about the world of politics. For example, research has shown that viewers of conservative media such as Fox News are more likely to believe that weapons of mass destruction were discovered in Iraq and that evidence of links between Iraq and al Qaeda were confirmed than audiences of liberal media such as NPR and PBS (Kull, Ramsay, & Lewis, 2003). In an election campaign context, partisan news media consist of information favoring their audience’s preferred candidate and negative information about the opposing candidate. Thus, it can be expected that partisan media use may lead people to form positive beliefs about ingroup members (candidates a partisan media outlet is in favor of) and negative perceptions about outgroup members (candidates a partisan media outlet is opposed to). Some research, indeed, has demonstrated that partisan media promotes inaccurate beliefs about outlet-opposed political candidates (Garrett, Long, & Jeong, 2019).

Beyond the direct relationship between media use and beliefs, which prior studies mainly focused on, this study examines whether and how political beliefs are associated with citizens’ voting intention. People use many kinds of heuristics to help make sense of their environments including politics or public affairs (Sniderman, Brody, & Tetlock, 1991), such as party affiliation, ideology, and candidate appearance (Lau & Redlawsk, 2001). Party identification and political ideology play perhaps the most central roles in citizens’ evaluations of candidates (Lau & Redlawsk, 2001). The labeling of social groups, which are frequently presented in news media, plays a causal role in creating individuals’ perceptions or beliefs about certain social groups (Mutz & Goldman, 2010). This can be the case in the relationship between partisan media use and political beliefs associated with political candidates as discussed above. This study argues that such perceptions or beliefs in turn play influential roles in forming individuals’ political attitudes and behaviors because they serve as reference cues for individuals when they process information such as when it comes to deciding whom to vote for. Research demonstrates that some individuals make decisions by using heuristics as substitutes for factual political knowledge (Conover, 1981) and as shortcuts to organize and process enormous amounts of information from various media sources (Caprara & Zimbardo, 2004). For example, stereotypes about female candidates can be used as information shortcuts when voters determine their choices in various election settings (Amalia et al., 2021; Anzia & Bernhard, 2022). Therefore, political beliefs associated with candidates’ demographic characteristics, which might be formed from partisan media use, may also serve as heuristic cues when people make a decision about whom they will vote for. Based on these discussions and previous studies, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: Exposure to partisan media (i.e., liberal media and conservative media) is related to beliefs about a female president in the same direction as political ideology and partisanship.

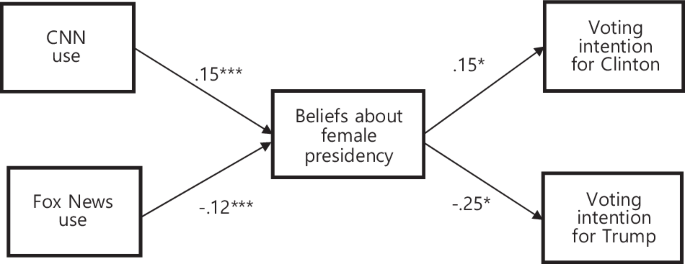

H3: Beliefs about a female president will be associated with respondents’ voting intention toward presidential candidates. That is, beliefs about a female president (i.e., one’s perception that their nation is ready to elect a female president) will be positively associated with one’s voting intention toward a female presidential candidate and negatively associated with the female candidate’s opponent, who is a male candidate.

H4: Beliefs about a female president will mediate the relationship between politically-slanted media use and voting intention toward presidential candidates.

Overview of studies

This project included two studies—one from South Korea (Study 1) and one from the U.S. (Study 2). The 2012 Korean presidential election and the 2016 U.S. presidential election provided opportunities to study the relationship between individuals’ likeminded media use and their political beliefs related to female candidates. In South Korea’s 2012 presidential election, Geunhye Park, the first female presidential candidate in Korean history, ran as the candidate of the Saenuri, a leading conservative party, thus offering an opportunity to examine beliefs about gender’s role in politics. In the U.S., Hillary Clinton, the first female candidate to be nominated for president by a major U.S. political party, ran as the Democratic Party’s nominee for president of the United States in the 2016 election. Research has shown that media play a significant role in politics and media coverage has placed women at a disadvantage by, for instance, disproportionally reporting on the physical appearances and family lives of female politicians, reinforcing gender stereotypes regarding women (Carroll, 2009). Numerous studies have also shown that such media coverage may be more pronounced if the partisan media’s political slant opposes a candidate’s political party (Jamieson & Cappella, 2008). Therefore, the direction of beliefs related to candidates (i.e., positive or negative beliefs) may differ depending on whether news media’s political slant is conservative or liberal. That is, in Korea, where a female candidate of a conservative party ran for president, it is predicted that liberal media use would be negatively related to perceptions of a conservative party’s female candidate (e.g., Korea is ready to elect a female president and female politicians are good at handling education and social policies), while conservative media use would be positively related to such perceptions. Meanwhile, in the U.S., where a female candidate of the Democratic Party ran for president, it is expected that conservative media use would be negatively related to beliefs about female politicians (e.g., the U.S. is ready to elect a female president), while liberal media use would be positively related to such perceptions. H1 and H2 were tested, but H3 and H4 were not tested in Study 1 because there were no measures of respondents’ voting intention. Study 2 replicates H1 and H2 in the context of the U.S., also testing H3 and H4 given that Study 2 included measures of voting intention toward presidential candidates from Democratic and Republican parties.