The enormous Zapad (or West) exercises, which have been running biennially since 2013, have a clear purpose — aiming to demonstrate Russia’s ability to menace and ultimately invade NATO members on the alliance’s Eastern flank.

Scheduled for September, Zapad-2025 is expected to be the largest Russian-Belarusian drill since 2021, with preparations already underway. While Moscow and Minsk describe this upcoming exercise as defensive, its structure, use of forward-deployed forces, and well-honed Russian propaganda about supposed threats from much smaller neighbors indicate a growing readiness for high-intensity conflict.

That has been underlined by a substantial Russian military build-up on the Eastern flank, with new bases and equipment flowing to units despite the continuing war against Ukraine. These are not yet at Cold War scale, but the direction of travel is clear. Taken together, these developments indicate a more confrontational stance toward the Euro-Atlantic community.

In April, General Christopher Cavoli, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), told the US Senate Armed Services Committee: “Russia’s ongoing effort to develop a massive military larger than its pre-war force indicates that [it] poses an enduring threat to the United States, our NATO allies, and global security.”

He added: “The Kremlin’s military is reconstituting and growing at a much quicker pace than most analysts had anticipated”, and that Russia has “a military larger than it was at the beginning of the war, despite suffering an estimated 790,000 casualties”.

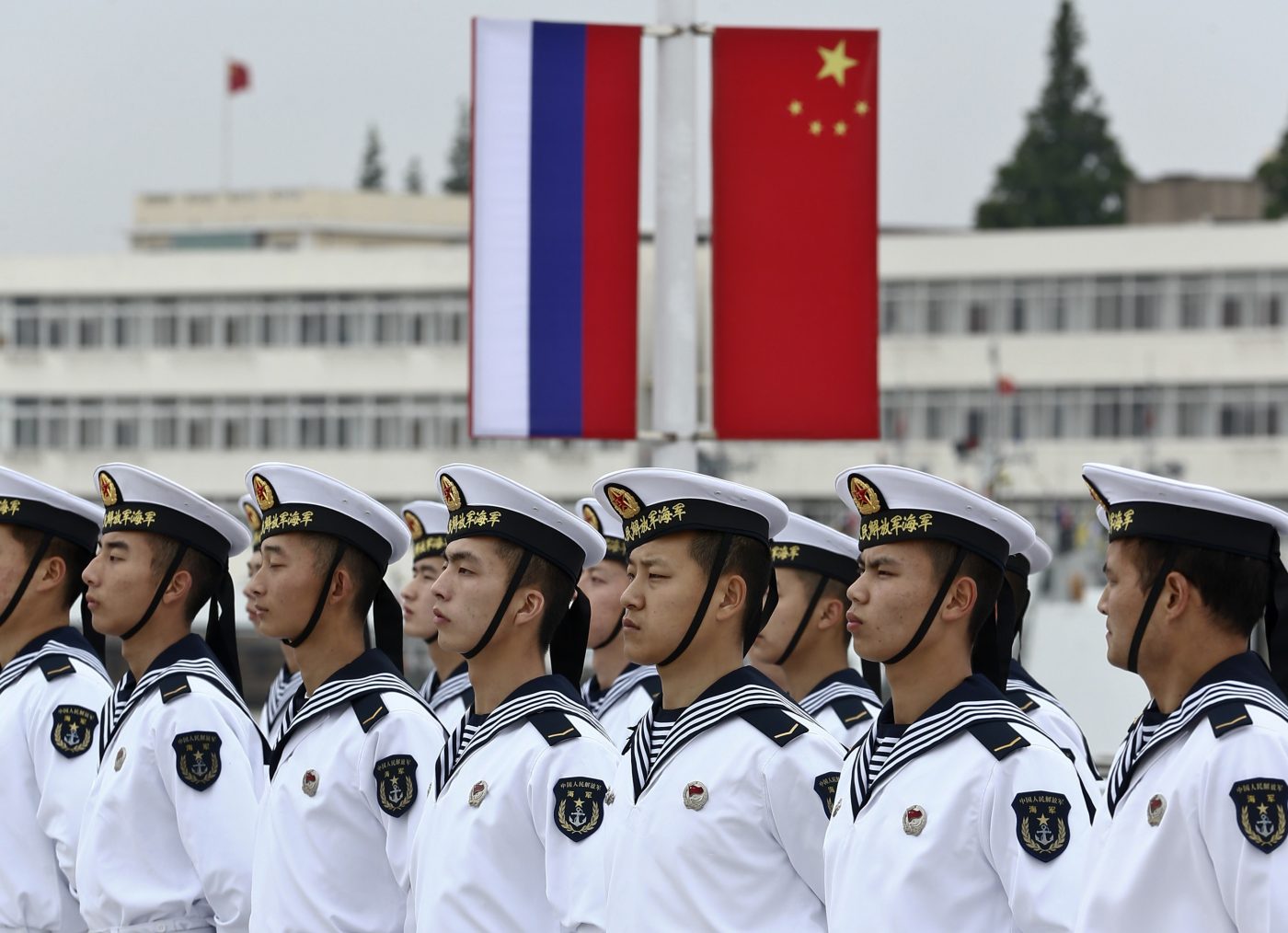

Zapad-2025 must be viewed in this context, not merely as symbolic, but as part of an intensifying strategy to rehearse and prepare for potential ground escalation on NATO’s Eastern flank beyond Ukraine. NATO’s new SACEUR, Gen. Alexus Grynkewich, has warned of a potential crisis as early as 2027, with Russia and China coordinating wars of aggression in Europe and Asia.

Russia and its Belarusian ally have already begun to muddy the waters to create uncertainty for NATO states. On May 28, a Belarusian minister said the exercises would be moved further from alliance borders to reduce tension. Two months later, the government said it “reserves the right” to deploy forces close to its borders, citing much smaller-scale NATO exercises.

For many in Poland and the Baltic States, Zapad-2025 appears less a routine drill than a rehearsal for a future blockade or invasion. This also includes fears of a potential strike through the Suwałki corridor, the narrow stretch of land connecting Poland and Lithuania, lying between Russia’s Kaliningrad oblast to the west and Belarus to the east. Belarus, whose foreign policy is now nearly identical to the Kremlin’s and which hosts Russian units attacking Ukraine, is again serving as a lever in Russia’s military policy against NATO.

The Zapad exercise series has long served as a platform for Russia to simulate escalation under a defensive guise.

In 2021, it was an enormous undertaking, involving around 200,000 troops and featuring simulated strikes on NATO positions. Months later, the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began.

Get the Latest

Sign up to receive regular emails and stay informed about CEPA’s work.

The 2025 iteration appears set to follow a similar pattern of testing allied response times, exploiting grey zones in doctrine, while also testing multi-domain force application with drones and robotics.

It’s likely the Zapad organizers will claim their drills involve no more than 13,000 personnel to avoid triggering Chapter VI of the OSCE Vienna Document of 2011. That would force it to invite all OSCE member states to send observers.

In fact, according to various estimates, Zapad-2025 could potentially involve from 100,000 to 150,000 troops. This number is lower than Zapad-2021, but should not be underestimated, considering the more active involvement of different types of weaponry and a high number of participating troops. By contrast, NATO’s biggest exercise since the end of the Cold War, Steadfast Defender in 2024, involved 90,000 personnel.

The current backdrop is perhaps grimmer than at any time since the first Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014. Gen. Cavoli said: “The Kremlin openly communicates its desire for an alternative to NATO as the European security architecture, to expand Russia’s military, and to increase force presence in key locations along NATO borders.”

In recent years, the Kremlin has expanded its military units and built railways on the border with Finland, Norway, and Estonia, indicating potential conflict preparation. The Kremlin has also bolstered the presence of a variety of weaponry, such as long-range missile units, air defenses, and aviation assets, in Belarus. Long-dormant airfields are being refurbished.

One of the latest moves was President Putin’s announcement of plans to place the Oreshnik intermediate-range ballistic missile at military sites in Belarus. The Kremlin also recently decided to construct a new military base near the Finnish border, following Finland’s decision to join NATO.

Moreover, Russia’s conventional moves are increasingly fused with non-kinetic hybrid pressure. Over the past six months, the Kremlin has stepped up sabotage, cyberattacks, propaganda, and proxy disruptions across Europe, particularly along NATO’s Eastern flank. These efforts often spike around military exercises, as was observed during Zapad-2021.

Zapad-2025 presents a complex multi-dimensional challenge for the European and Euro-Atlantic community. Western leaders must not only consider the implications of such large-scale military drills as Zapad-2025 but also be ready to counter associated hybrid pressure campaigns aimed at undermining their democratic cohesion.

For frontline states such as Poland, the Baltic states, and Finland, these developments demand urgent adaptation in military deterrence posture, force preparedness, and joint exercises. NATO’s planning must now assume that upcoming and future Zapad-type military drills may involve real-time troop movements capable of triggering localized crises along NATO’s eastern and northern flanks.

As Zapad-2025 approaches, NATO and EU leaders should treat it not as posturing, but as a strategic signal in Russia’s long-term strategy to reshape the balance of power in Europe.

And there may not be much time left to fix allied defenses. As Grynkewich said in July of plans to raise NATO spending: “Time is of the essence, and I intend to keep highlighting that and letting everyone know that we’ve got to move out and we’ve got to move quickly,” he said.

Maksym Beznosiuk is a strategic policy expert and director of UAinFocus, an independent platform connecting Ukrainian and international experts around key Ukraine issues. His work spans EU-Ukraine cooperation, Ukraine’s recovery, energy and raw materials policy, governance in conflict-affected regions, and the security-policy nexus.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions expressed on Europe’s Edge are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

Europe’s Edge

CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America.