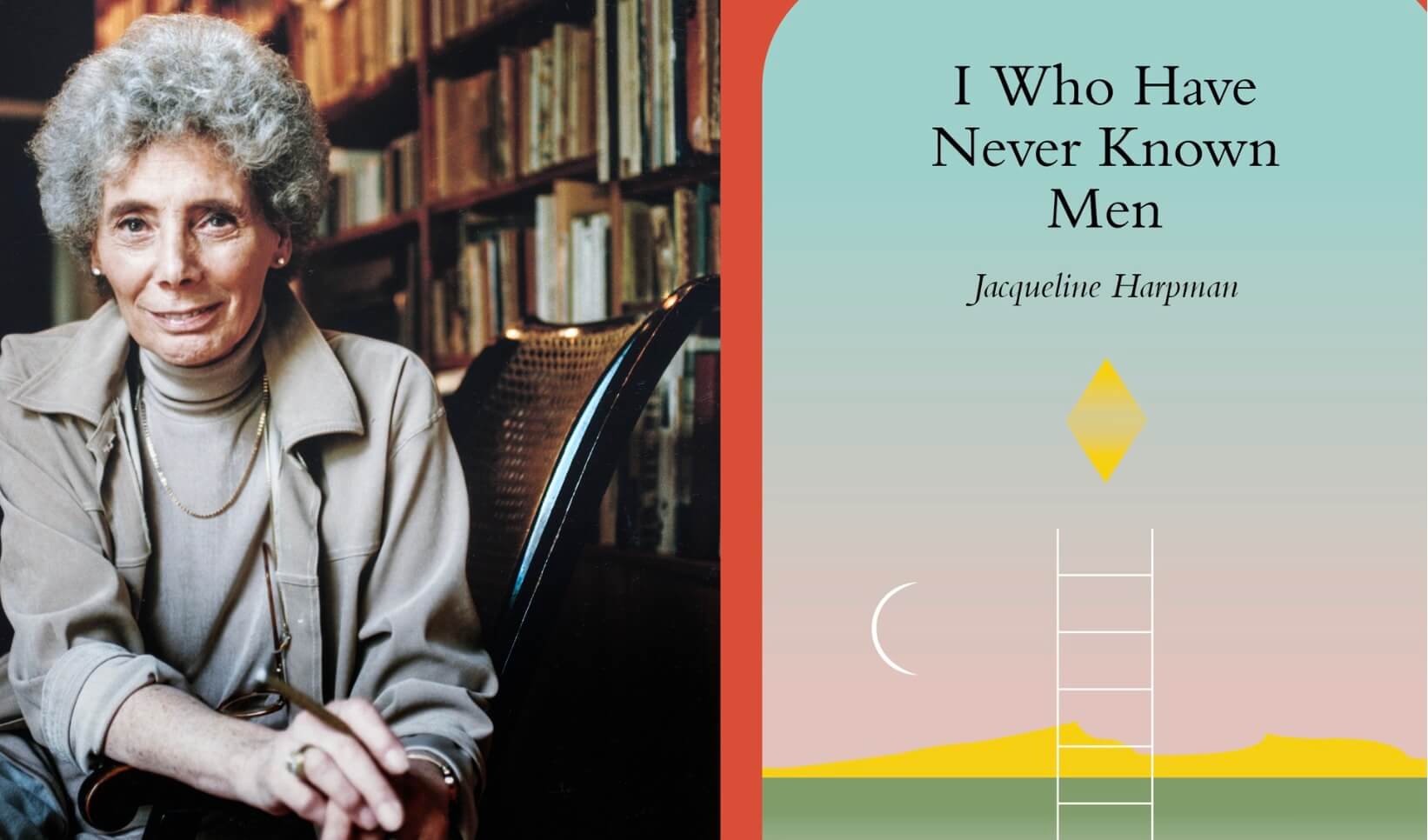

Jacqueline Harpman is the author of ‘Orlanda’ and ‘I Who Have Never Known Men.’ Courtesy of Seven Stories Press

Jacqueline Harpman is a dead Holocaust survivor who went viral on TikTok, and literary translators should be working overtime to translate all of her funny, poignant novels as soon as possible.

Harpman was born in 1929 in Belgium to Jeanne Honorez and Andries Harpman, who was Jewish. In May 1940, the same month Nazis invaded Belgium, her family moved to Casablanca, Morocco, according to an interview with the Belgian journalist Joëlle Smets. Harpman faced institutional antisemitism in Morocco, then a French protectorate, and moved back to Belgium in October 1945, after the war ended.

In Belgium, Harpman became both a celebrated author and a professional psychoanalyst. She published the slim, dystopian novel I Who Have Never Known Men in French in 1995, and it was translated soon afterward into English by Ros Schwartz. In 2022, in the wake of the first Trump administration and the popularity of dystopian fiction like The Handmaid’s Tale, the book was re-released. Book bloggers on TikTok, who usually seem more interested in romance and fantasy, did the seemingly impossible and made a nearly 30-year-old Belgian novel in translation go viral, a rare win for the crazies among us who envision a world where everyone has impeccable literary taste. It sold 100,000 copies in the U.S. last year.

I Who Have Never Known Men is written from the perspective of a girl who grows up in a mysterious bunker with 39 women. The girl has lived in the bunker for as long as she can remember, kept alive for unknown reasons with two paltry meals per day, and the reader gets the impression that she never really thought to question this life until she began puberty.

The onset of the nameless girl’s sexual desire marks the beginning of the plot. Her newfound curiosity about men grows into a need to understand the entire world, making her a rebel and a leader. Even though she has less experience in the ‘before’ world than any of the women in the bunker, she is the one who craves it most. And when the opportunity comes to escape, our heroine leads the way.

Every page of this book drips with suspense as the narrator goes on an adventure to understand where she is, how she ended up there and whether the planet she lives on is even Earth. The lack of information is part of the cruelty. Her odyssey dramatizes the journey every person must go on to understand their identity, even if they didn’t grow up in a bunker on an ambiguous planet.

The author’s writing style combines a childlike sense of wonder with a woman’s philosophical insights on freedom, resilience and what it means to be human. When the women complain that it’s inhumane to be denied the privacy of a bathroom, the narrator makes a startling point. “If the only thing that differentiates us from animals is the fact that we hide to defecate, then being human rests on very little.” Then there’s the dramatic statement she makes about finally getting to climb the stairs to leave the bunker: “I think I’d be prepared to relive twelve years of captivity to experience that miraculous ascent.”

It’s tempting to draw a connection between the novel’s dystopian themes and the Holocaust, as many readers have. But doing so risks detracting from the book’s inventiveness, and oversimplifying the genocide. On Sept. 9, Seven Stories Press is reprinting the only other Harpman novel that has ever been translated to English, also by Schwartz. That hilarious and imaginative novel, Orlanda, won the prestigious French literary award the Prix Médicis in 1996. It’s a parody of Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando, where the main character is a man who suddenly becomes a woman halfway into the story, then goes on with her life as if hardly anything strange has happened.

In Harpman’s novel, the main character is a literature professor named Aline who is preparing to give a lesson about Orlando when part of her consciousness splits off. The departed consciousness, Orlanda, colonizes a handsome young man’s body and uses it to indulge all the unsavory desires (she constantly goes cruising) that Aline repressed when they lived in the same body.

While Orlanda is out living her best life, Aline is doing the only thing she knows how to do — study literature. It bothers Aline that when studying Orlando, some scholars focus on Woolf’s real-life inspiration for the novel. “You shouldn’t look for the meaning of a book anywhere but within the book itself, not in the author’s life or in the writings of critics and other commentators,” Aline says.

That task seems easy enough for Orlanda, but what about books that appear to be autobiographical? According to Schwartz, one novel Harpman wrote that hasn’t yet been translated into English, En quarantaine, is likely based on Harpman’s experiences in Morocco.

At 13, Harpman was made to attend a lecture by the fascist French politician Jacques Doriot, during which Doriot made “a torrent of vile remarks against the Jews,” according to a 1992 interview with the literary scholar René Andrianne. “I have not yet recovered from not having had the courage to stand up and shout at the abomination,” Harpman said.

En quarantaine takes place in 1942 Casablanca, and features a Jewish girl who gets suspended from school after contradicting a French poet’s claim that it’s sweet to die for your country. The teen’s outspokenness recalls the courage Harpman wished she had had. “There is an undercurrent of antisemitism in the school’s accusation” that the protagonist isn’t patriotic enough, Schwartz wrote in a synopsis of the book she shared with the Forward.

But when Andrianne asked Harpman whether Jewishness plays a role in her work, Harpman said no, “except unconsciously.”

Harpman’s statement about the role of Jewish identity in her work seems to reflect not necessarily internalized antisemitism, but a hope that her work would not be pigeonholed. Harpman’s stories are imaginative, thought-provoking, and universal. Her stream-of-conscious narrative style, her sense of humor and the way she explores gender all mirror the legendary Woolf.

For these reasons and more, my American chauvinism forbids me from accepting the notion that I can’t read all of Harpman’s books in English. Luckily for me, Schwartz said that the UK Penguin Random House imprint Vintage is “currently looking at Harpman’s other works to decide which ones to have translated in time for the centenary of her birth in 2029.”

I’ll mark my calendar.