States and regulated industries have challenged the scientific determination underpinning federal regulation of greenhouse gas emissions before, but the so-called endangerment finding has never faced direct opposition from within—until now.

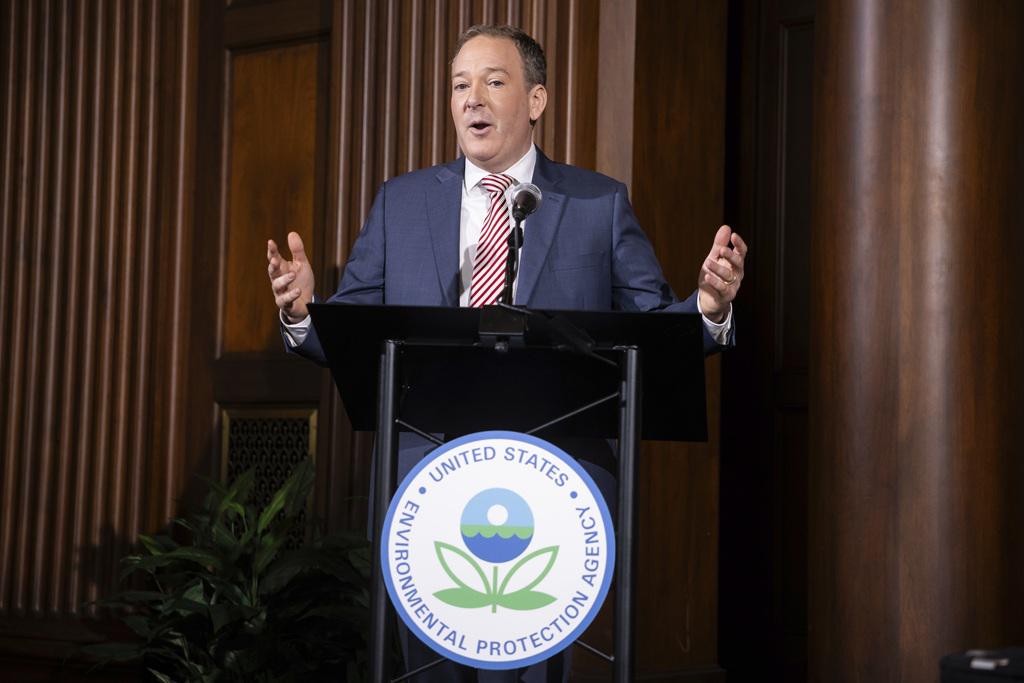

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administrator Lee Zeldin announced the agency’s formal proposal to rescind the 2009 finding at a truck dealership in Indiana last week, sparking regulatory uncertainty and sharp criticism from various stakeholders. The endangerment finding, required by a 2007 Supreme Court ruling in Massachusetts v. EPA, offered voluminous scientific evidence that greenhouse gas emissions were a threat to human health and welfare.

It has subsequently been relied upon to shape EPA rules. The agency only has the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles, power plants, and other sources through the Clean Air Act. If the endangerment finding is overturned, those regulations would have no basis to continue. Doing away with the endangerment finding may also undermine efforts to seek environmental justice in the courts.

“We’re in a very dark era for environmental law,” Jason Rylander, legal director at the Center for Biological Diversity’s Climate Law Institute, told the Prospect in an interview. “Lee Zeldin is turning the Environmental Protection Agency into the environmental pollution agency, and they are simply turning a blind eye to anything that could potentially undermine industry profits.”

The agency’s foremost claim is that it can only regulate localized pollutants rather than regional or global ones. In the notice of proposed rulemaking on the Federal Register, EPA cites a Department of Energy report authored by five climate skeptics “who are all outside the mainstream of climate science,” Rylander said. That report was incorporated into Zeldin’s review, which preceded the agency’s “reconsideration” of the finding. Rylander also expects EPA to assert the need for a cost-benefit analysis and argue that each greenhouse gas covered by the statute, from carbon dioxide to methane, should be considered individually rather than collectively.

EPA must solicit and respond to public comment before finalizing the rule; Zeldin hopes to do so by the end of the year. At that point, the ball is likely to land in the courts, which have long ruled in favor of the declaration. Ruling against it would be unprecedented.

SINCE RETURNING TO THE OVAL OFFICE, one of President Trump’s central goals has been to unleash American energy. Revoking the endangerment finding would do much to achieve that goal, as big emitters and high-polluting sectors would essentially be off the hook for worsening the climate crisis.

In fact, the post–endangerment finding landscape is already coming into focus, even before the repeal is finalized. The same day as the endangerment finding proposal was announced, EPA also signaled its intention to eliminate limitations on carbon dioxide for cars and trucks. The elimination of all federal carbon emission standards could paradoxically make it easier for states like California to reinstate their emissions limits without a waiver from the federal government, since they wouldn’t have to ask to diverge from a federal rule.

In addition, last week, EPA issued an interim final rule delaying methane limits on oil and gas operations. So while the agency says it remains committed to its “core mission of protecting the environment,” rolling back the backbone of U.S. climate regulation is sure to enable more pollutive extraction of fossil fuels, which will deprive Americans of the clean air and water Trump promised them on the campaign trail.

The methane delay went into effect on July 31, the day it was published. Because EPA is not changing the rule, only delaying it, the agency is not required to provide advance notice or seek public comment because “such procedures are unnecessary and impracticable,” it said. Instead, the agency has opted to draw conclusions based on “ongoing conversations with regulated entities.”

The elimination of all federal carbon emission standards could paradoxically make it easier for states like California to reinstate their emissions limits.

Delaying methane limits exposes communities to the worst of climate change, but they have no say in the matter. Maggie Coulter, an attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity’s Climate Law Institute, told the Prospect the process has been reduced to “a conversation between EPA and industry,” adding that the Trump administration has been limiting opportunities for public engagement more frequently.

“This backdoor move will allow more dangerous leaks to spew unchecked from oil and gas facilities, putting lives at risk. The Trump administration is again putting oil and gas industry profits above people’s health and safety. Taking no public input before this disastrous rule goes into effect is icing on this rancid cake,” she said.

Lauren Pagel, policy director at Earthworks, echoed the sentiment. “Unfortunately, this administration does not seem to care about public engagement,” she told the Prospect.

In its current form, the rule delays ongoing and mandatory leak inspections, as well as the deployment of remote-sensing tech under the Super Emitter Program, until 2027. It also postponed the continuous monitoring of thermal emissions until later this year. Coulter told the Prospect that these delayed provisions, which cover “low-hanging fruit” like leaking, venting, and flaring, are a reprieve for regulated industry. However, regulated industry remains fractured over the Trump administration’s doctrinal deregulatory push, with some taking advantage of the opportunity to write the rules and others exercising caution toward the U-turn in rulemaking.

“There are just so many ways in which the gutting of EPA administrative staff, the elimination of EPA scientists, and the elimination of long-standing regulations … will undermine enforcement of environmental law, contribute to uncertainty among the regulated community, and have very serious public-health impacts,” Rylander told the Prospect.

For its part, Earthworks will fill a crucial gap by continuing to track methane emissions, which have risen dramatically since the early 2000s. The organization uses optical gas imaging technology to monitor greenhouse gas emissions, compiling data to identify bad actors and better understand the effects of pollution on surrounding communities. Earthworks intends to challenge the rule.

“The entire climate community is coming together and activating its members,” Pagel said. Among them is the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). Founded on Long Island in 1967, the advocacy group helped ban the use of DDT and has since grown into an environmental protection powerhouse. In a statement, Fred Krupp, president of EDF, vowed to fight back.

“Administrator Zeldin is attempting to delay safeguards that have been in place for over a year, and he’s attempting to do it without public input,” he said. “EDF will challenge this unlawful delay to ensure the American people get the benefits of these protections against methane pollution.”

EXACTLY 125 DAYS AFTER the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the EPA endangerment finding as “unambiguously correct” and supported by ample scientific evidence, Superstorm Sandy made landfall in the New York tristate area. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the massive storm killed 72 people across the mid-Atlantic region and northeastern U.S., also causing tens of billions of dollars in economic losses.

My hometown is less than three miles from the beach on the South Shore of Long Island. When Superstorm Sandy hit, I was 12 years old. The highly destructive post-tropical cyclone left over a foot of water in the single-story home I grew up in. Zeldin’s hometown of Shirley, New York, in Suffolk County, is further inland than mine, but Superstorm Sandy did not spare it back then. I imagine the next disaster won’t either.

For the better part of my life, I lived in the shadow of the E.F. Barrett Power Station. Owned by the Long Island Power Authority (LIPA) and operated by National Grid, it is one of the largest and most antiquated power plants in the region. The facility emits far greater levels of pollutants than modern combined-cycle power plants, which generate electricity using gas and steam turbines. Its operations require large volumes of water for cooling, and the resulting thermal pollution has reportedly harmed the surrounding marshland ecosystem. LIPA has plans to decommission the power plant’s two steam turbines by 2030 and has discussed repurposing its facilities for battery storage or offshore wind integration. However, given that the already exponential up-front costs associated with clean-energy projects are slated to go through the roof, reducing environmental impact could become a pipe dream.

These are the realities of life for millions of Americans living with the effects of fossil fuel pollution and extreme weather fueled by climate change. Zeldin has decreed that things are only going to get worse.