Sung Je Byun and Kelly Klemme

Oil prices have swung dramatically in recent years, shaped by geopolitical conflicts, evolving global demand and shifting energy policies. While media attention tends to focus on the impact on major oil producers and international markets, the consequences of these fluctuations are often deeply felt in smaller communities across the U.S. regions where oil and gas activity form the backbone of the local economy.

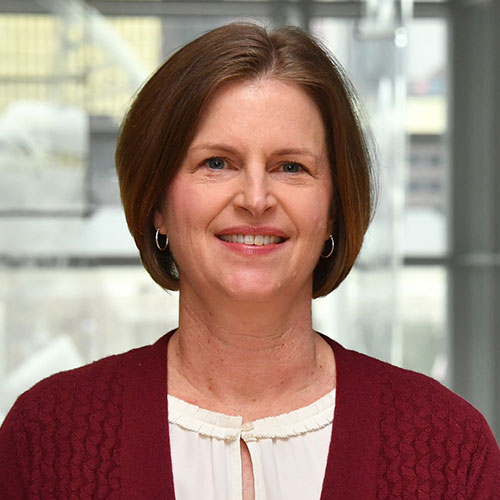

This led to a significant reduction in the number of active drilling wells (Chart 1). The prolonged period of low oil prices, lasting into early 2016, had a severe impact on oil and gas regions, where economies had previously boomed due to innovation in drilling technologies, high oil prices and the resulting surge in oilfield activities. Such prolonged weakness in oil and gas prices affects banks that serve these regions. As local economic conditions deteriorate in step with falling oil prices, these institutions face specific vulnerabilities.

Boom-and-bust cycles impact oil and gas regions

The oil and gas extraction industry, comprising both upstream operations and oilfield services, impacts local economies by generating a broad range of employment opportunities including direct jobs in drilling and production, as well as indirect roles in supporting industries such as transportation, equipment supply and hospitality. The sector also contributes to local government revenue through taxes, royalties and lease payments, which can help fund public services and infrastructure.

The shale gas and tight oil boom, also known as the U.S. Shale Revolution, had significant economic impacts at the local, national and international levels. Despite these potential benefits, economic gains from oil and gas activity are often uneven across regions and reflect cyclicality in oil prices. This volatility can create economic instability and lead to boom-and-bust cycles in oil and gas regions heavily dependent on extraction.

For purposes of this article, oil and gas regions are defined as commuting zones where the share of employment in the oil and gas extraction industry exceeds the U.S. national average as of 2014.

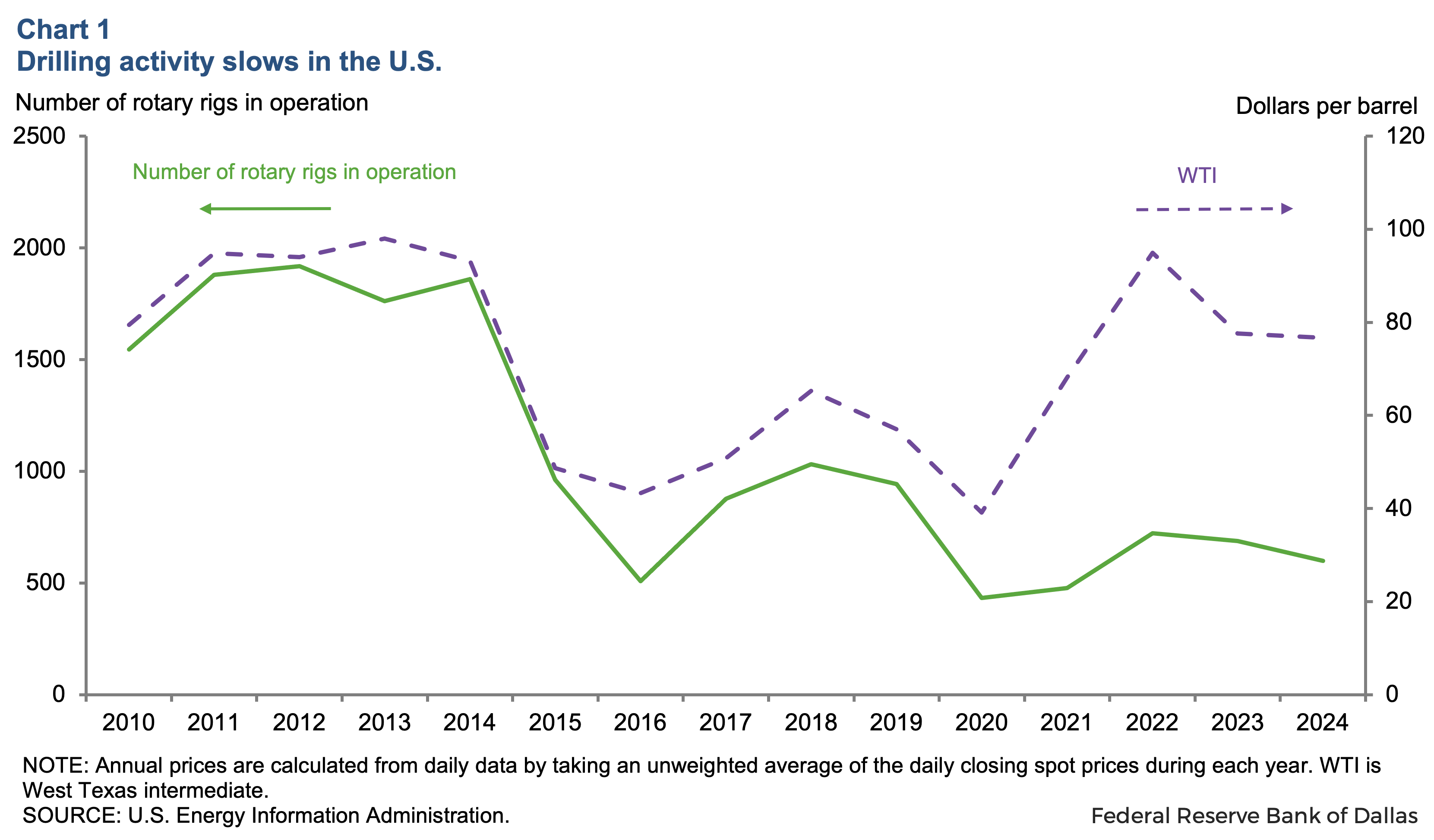

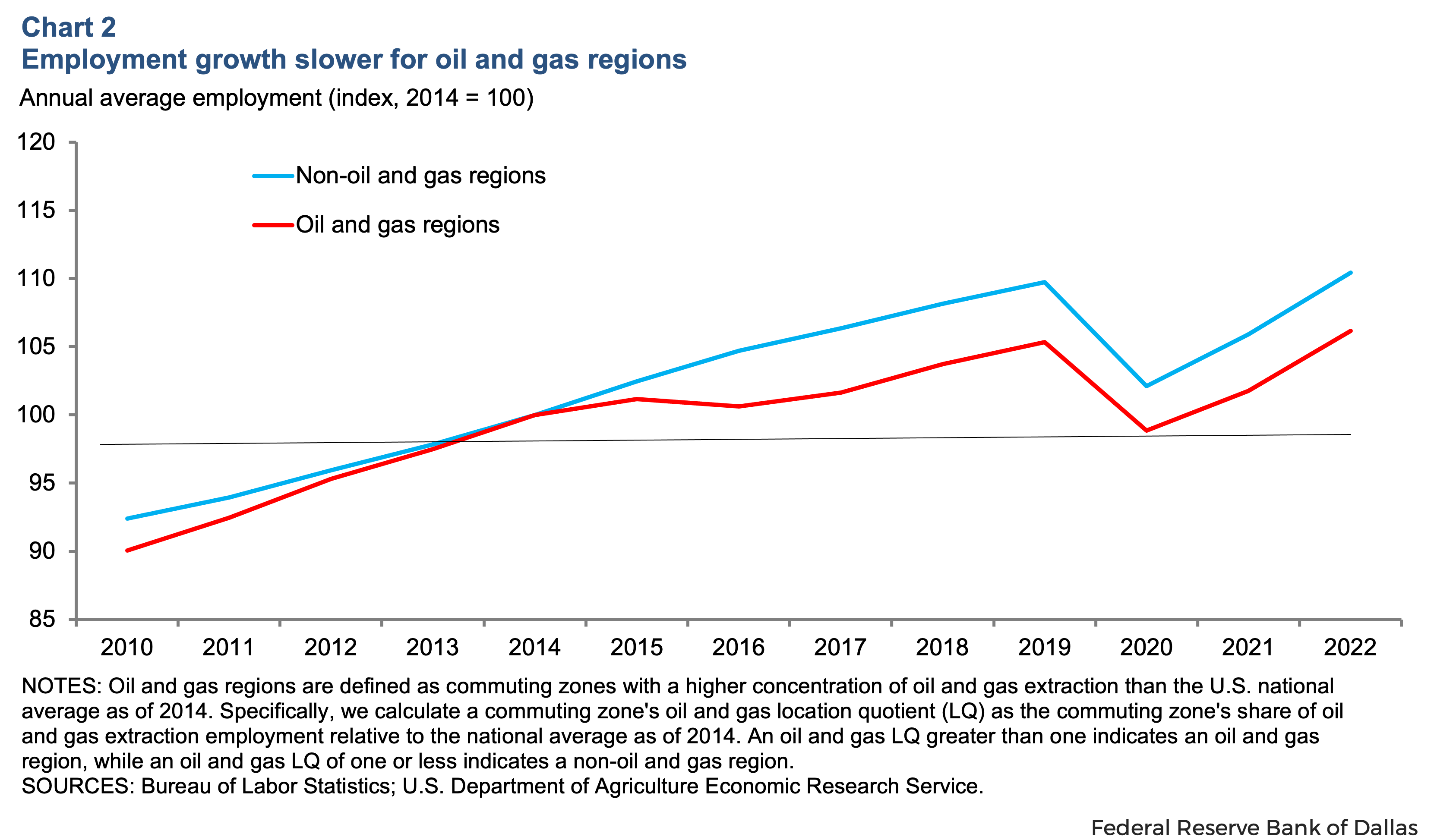

In oil and gas regions, the extraction industry represents a small part of the local economy. Oil and gas extraction employment is less than 5 percent of total employment, on average, in oil and gas regions. And, for half the oil and gas regions, oil and gas extraction employment is less than 2.6 percent . Despite relatively small direct employment, oil and gas regions experienced stronger growth in both total employment and total private wages compared with other regions before 2014. However, after 2014, these same oil and gas regions saw a marked slowdown in growth, resulting in widening gaps in both employment (Chart 2) and wages (Chart 3) relative to non-oil and gas regions.

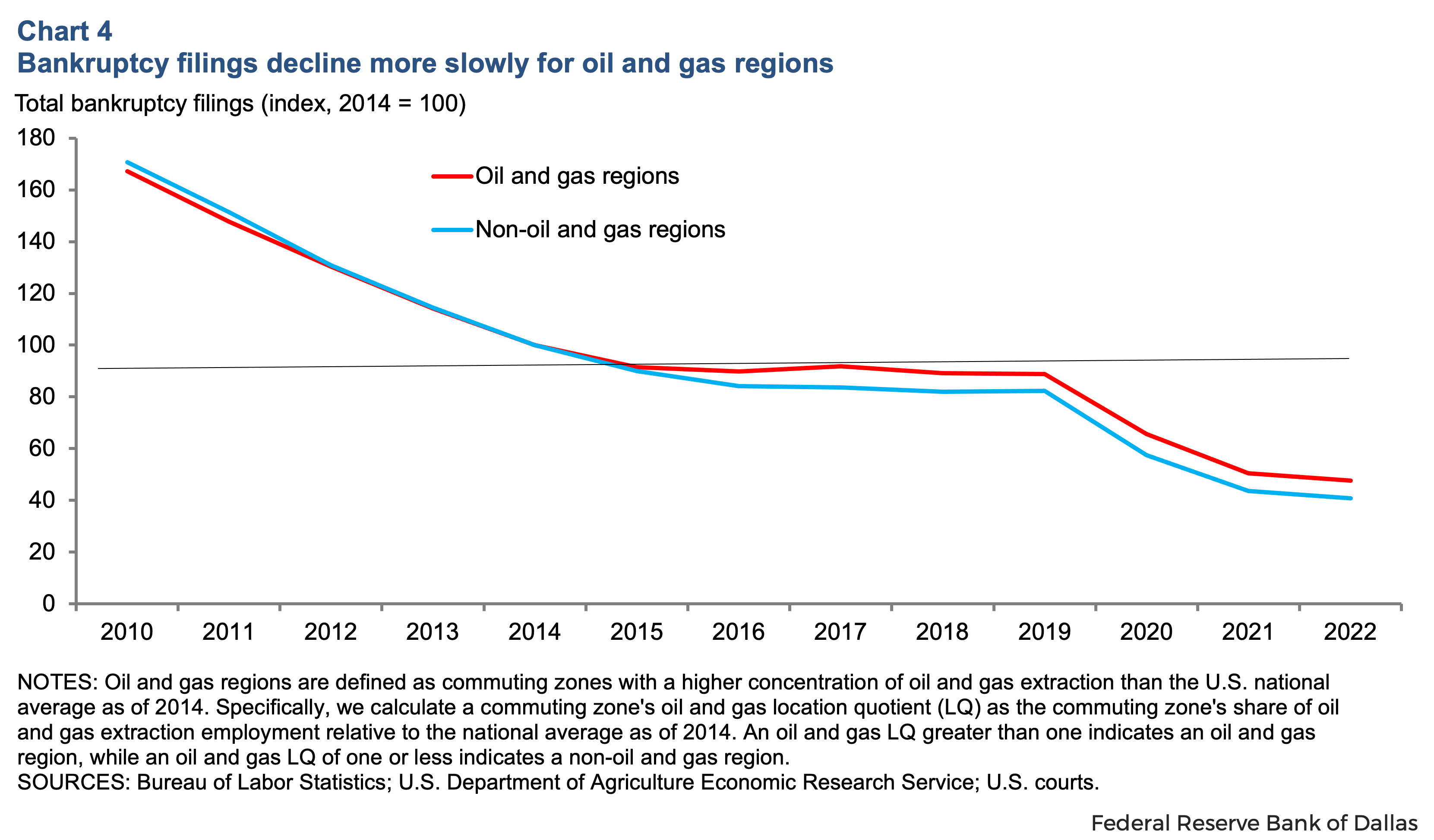

Prolonged low oil prices reduced incomes in oil and gas regions, slowing their recovery from the Great Recession. Although total bankruptcy filings fell sharply through 2014, the decline was slower in these regions and remained sluggish for another decade (Chart 4), largely due to persistently high consumer bankruptcies, which make up the majority of filings.

Oil price declines impact banks in oil and gas regions

The slowdown in these regions affected the banks operating there, which benefited from increased deposits and lending opportunities during the boom. Oil and gas banks are defined as those with above-average exposure to the extraction industry based on their share of deposits in oil and gas regions.

This article focuses on regional and community banks, which primarily operate within specific geographic areas or regions of the country. These banks typically serve local residents and businesses, emphasizing residential and commercial real estate loans. Therefore, regional and community banks tend to be more closely connected to local economic conditions than larger, national banks.

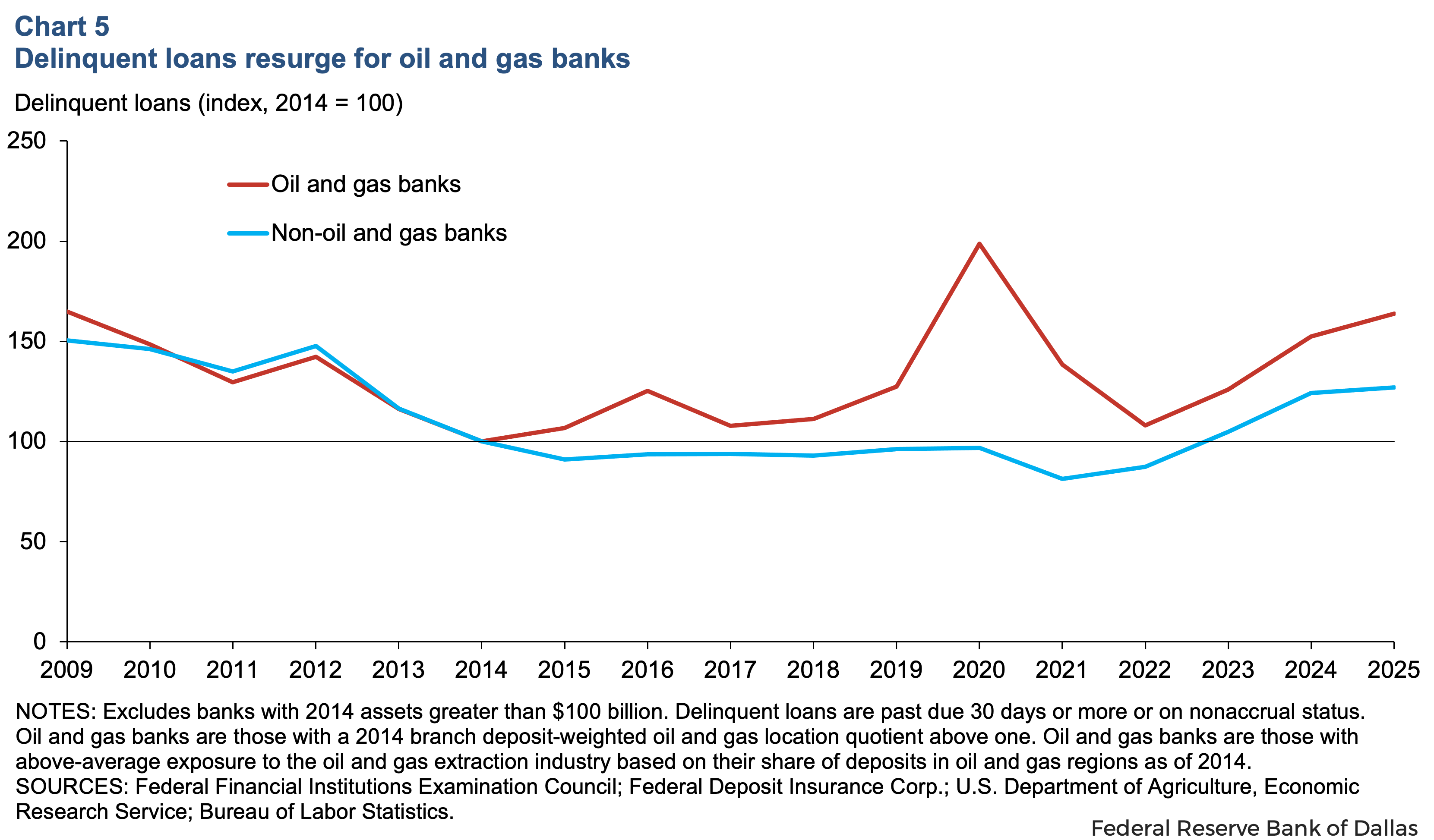

From 2014 to 2016, delinquent loans at oil and gas banks rose 25 percent, while delinquent loans at non-oil and gas banks continued their steady decline since the Great Recession (Chart 5).

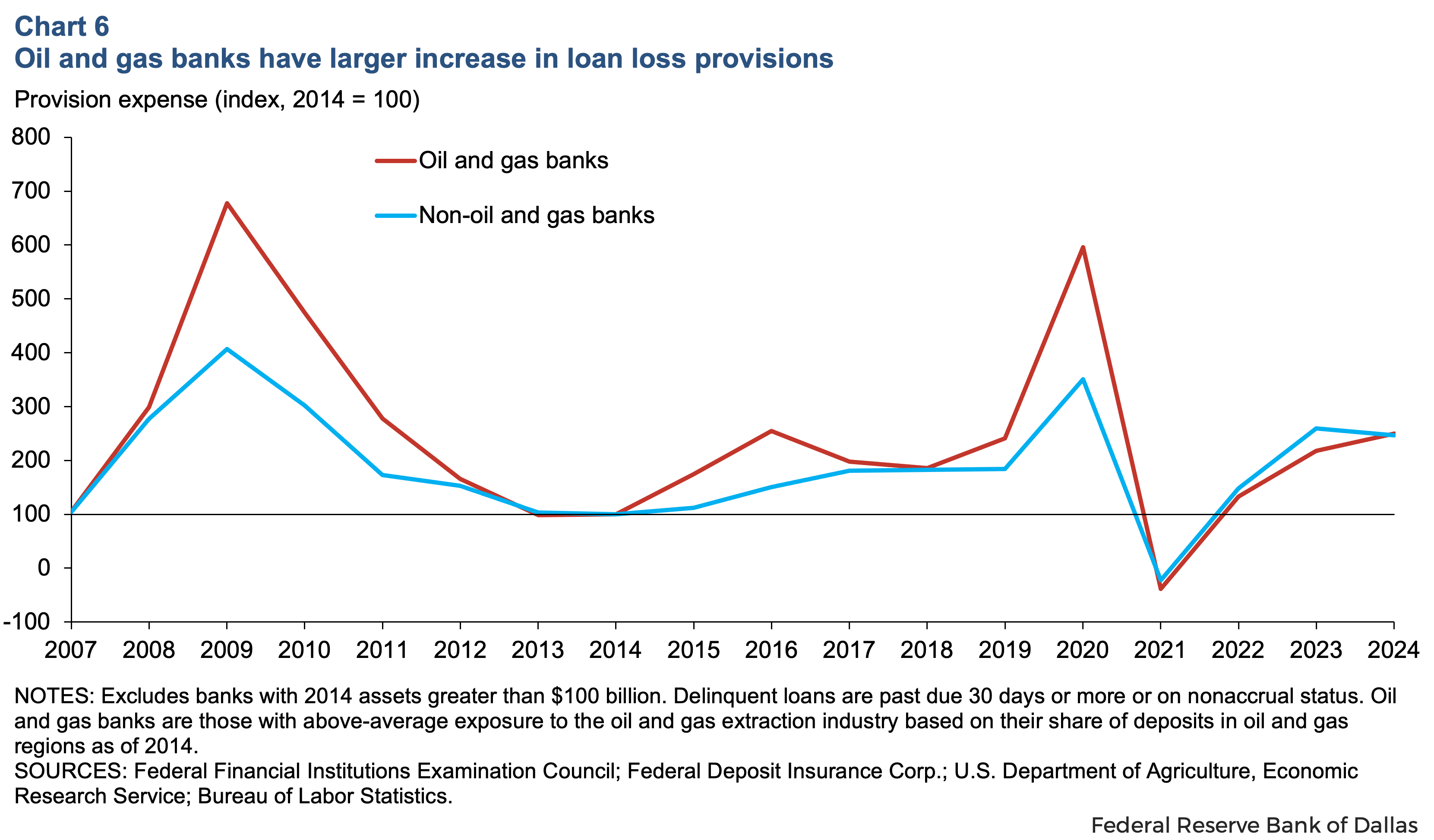

As loan quality deteriorated, these oil and gas banks also incurred larger increases in loan loss provision expenses, partly due to falling collateral values linked directly or indirectly to oil and gas assets (Chart 6). While provision expense for non-oil and gas banks rose 50 percent from 2014 to 2016, the increase for oil and gas banks was three times higher.

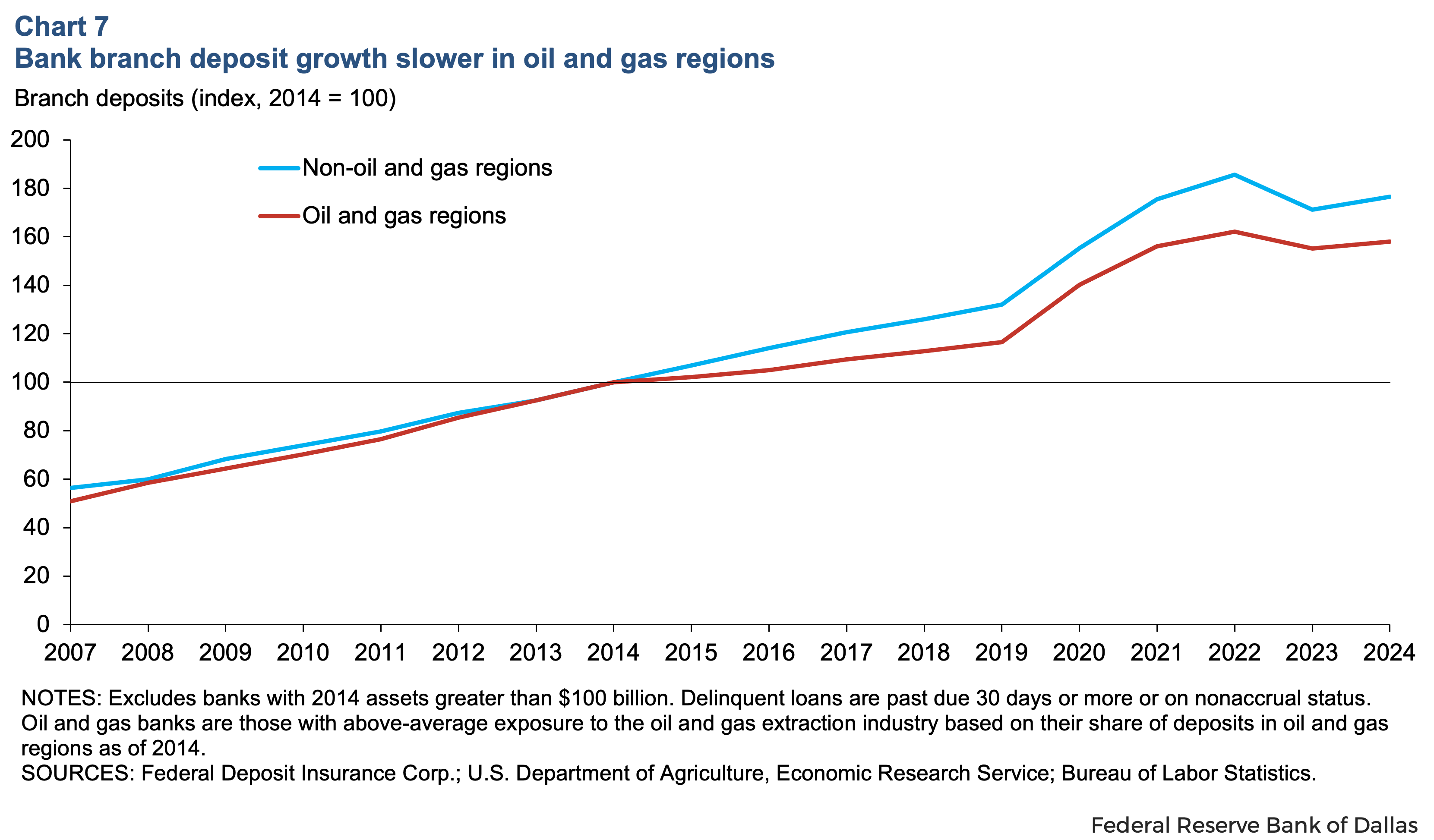

Deposit growth for bank branches in oil and gas regions was also slower than growth for banks in non-oil and gas regions (Chart 7). From 2014 to 2016, deposits at bank branches in oil and gas regions increased 5 percent, much lower than the 14 percent increase for bank branches in non-oil and gas regions . On top of these pressures to asset quality and funding, the local economic slowdown for these banks meant weaker demand for loans and other financial services.

While the 2014–16 oil price downturn did not result in widespread bank failures, it strained the operations of banks with large exposure to oil and gas regions. The cyclical nature of the oil and gas sector means these banks remain vulnerable during downturns. This was evident again in 2020, when the sharp decline in oil prices, driven by a pandemic-induced drop in demand, led to a rise in delinquent loans and loan loss provisions for banks operating in oil and gas regions. With oilfield activity continuing to slow down in mid-2025, another prolonged period of low oil prices could present serious challenges for banks operating in oil and gas regions.

Banks and regulators can mitigate the impact of oil busts

Banks can take several steps to protect themselves from the kind of stress caused by events like the 2014–16 oil price crash. One key strategy is diversification, spreading their business across different regions and industries so they’re not too dependent on a single area or sector. Banks can also set aside extra funds during good times to help cover losses when things go south, a practice known as dynamic provisioning. While the cyclical nature of the oil and gas sector is difficult to fully capture using historical data or quantitative models, banks can strengthen their preparedness by applying qualitative adjustments, or Q factors, to credit loss estimates under the current expected credit loss (CECL) accounting standard. Lastly, by improving how they assess the risks of lending, especially in areas tied to volatile industries such as oil and gas, banks can make more informed decisions that help them stay stable during downturns.

About the author

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.