Twenty-five years ago, the bipartisan Hart-Rudman Commission described the State Department as a “crippled institution.” Since then, things have only gotten worse. Traditionally, the State Department’s six regional bureaus and their country-specific desks handled the entire world. Over the past 20 years, the department has created dozens of single-issue offices to handle everything from food security and climate change to women’s empowerment. Some countries such as Iran, Venezuela, and even Tibet now have dedicated, independent offices.

Anyone who has taken a course in economics understands the law of diminishing marginal returns. At some point, the benefit of adding another worker or widget is outweighed by the cost. That is the case at the Department of State. Too many bureaucrats, in too many offices, are chasing too many approvals to get anything done in a timely manner.

Lacking the discipline of profit and loss, government bureaucracies will expand according to the resources provided. No bureaucrat was ever promoted for saying “I need a smaller staff.” At the height of the Cold War, in 1970, the Department of State had 3,000 Foreign Service officers—the diplomats who staff our embassies abroad and policymaking offices in Washington. Today that number is nearly 14,000. Like a restaurant with too many waiters, the department’s policy approval process has become a time-consuming, inefficient maze.

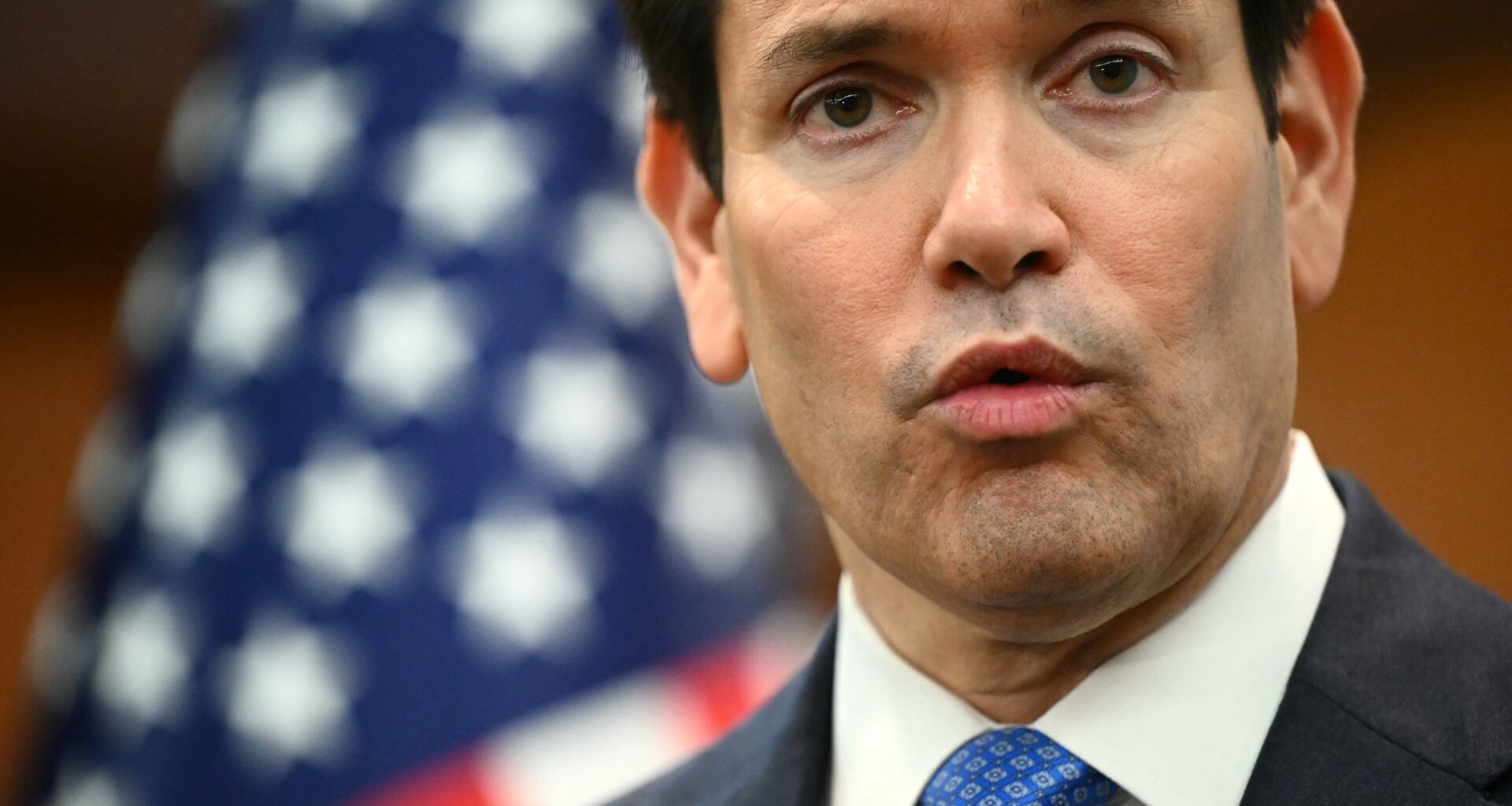

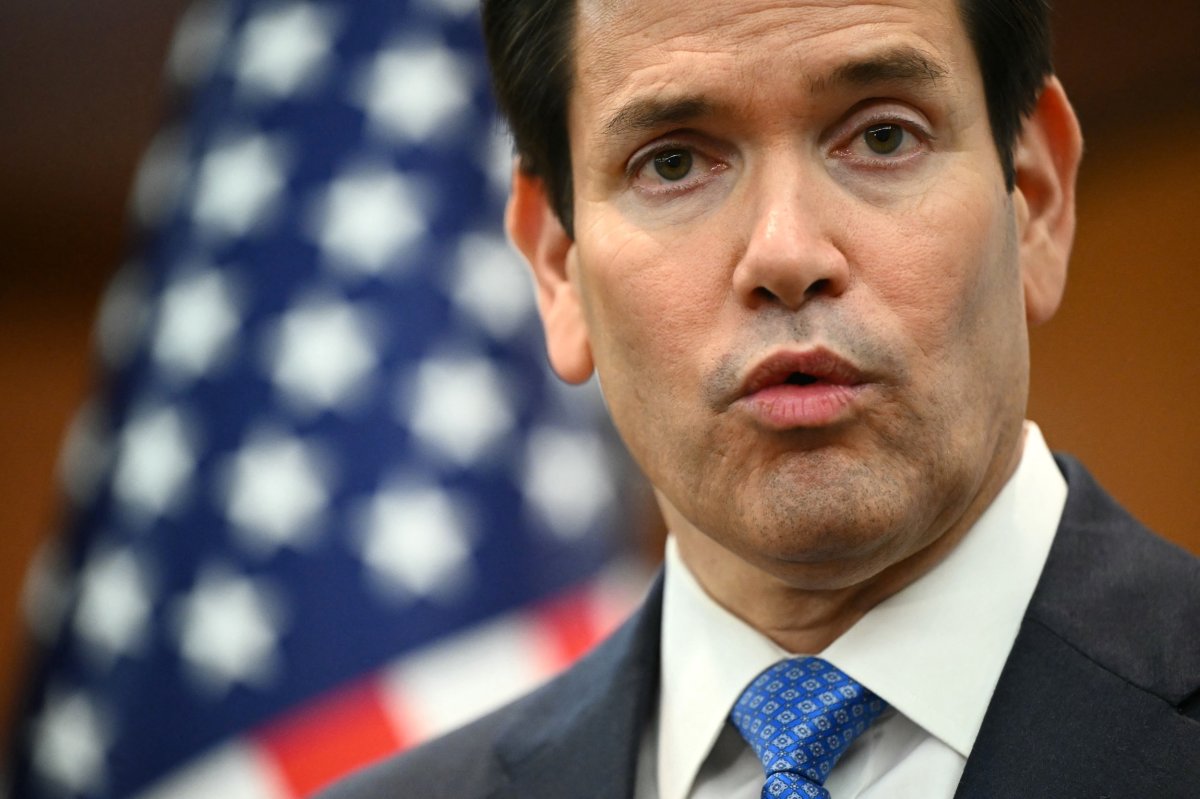

Secretary Marco Rubio recently noted that policy memos require more than 40 signatures before hitting his desk. This suffocating “clearance process” inevitably adopts the least controversial course of action, promotes groupthink, and makes the emergence of original ideas nearly impossible. The budget story is hardly better. The department’s inflation-adjusted budget has increased by 27 percent in the past decade alone. It would be difficult to argue that the quality of American diplomacy has increased by a similar amount.

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio gives a media briefing during the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting at the Convention Centre in Kuala Lumpur on July 11, 2025.

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio gives a media briefing during the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting at the Convention Centre in Kuala Lumpur on July 11, 2025.

Mandel NGAN / POOL / AFP/Getty Images

Marco Rubio is not the first secretary of state to realize that his department needed serious reform. Hillary Clinton launched the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review to address systemic problems. Rex Tillerson held listening sessions with employees, developed a reorganization plan, and made streamlining the department a top priority. Mike Pompeo told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that he intended to simplify the approval process and encourage creativity within the department. All these efforts faced stiff resistance from a variety of vested interests in the State Department, Congress, and Washington think tanks. Progress was minimal.

Secretary Rubio is the first to take effective action. He is rebuilding the professional diplomatic service and getting back to basics: Reducing unnecessary bureaucracy, streamlining decisionmaking, and focusing on core national interests.

Specifically, Rubio has folded USAID into the State Department, something that countries like Australia and the U.K. did years ago. He has placed many of USAID’s responsibilities with the newly reenergized regional bureaus, ensuring that assistance will be aligned with policy. He has closed many independent offices while preserving country desks, American citizen services, and diplomatic security functions. While 15 percent of the D.C. workforce was released, overall staffing is down only 2 percent and core functions have been preserved.

Reactions to Rubio’s reforms have been mixed. The former director general of the Foreign Service, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, has called the layoffs “cruel and unacceptable.” Did she and other critics think it was cruel to lay off construction workers when President Joe Biden canceled the Keystone Pipeline? Rubio’s leadership team cut only 1,300 out of a workforce of 27,000 U.S. civil servants and Foreign Service personnel. A much larger number departed government service under a generous voluntary program—offered not once, but twice—that provided up to six months of paid administrative leave. This strikes us as the antithesis of callousness.

Taking the opposite view of these critics is the nonpartisan Ben Franklin Fellowship, of which we are both members. Composed of current and retired foreign affairs professionals, the fellowship has long supported American sovereignty over globalization, meritocracy over DEI, and the careful stewardship of resources over continuous government growth and budget deficits.

A few weeks ago, an anonymous poem circulated in the State Department. Entitled, “Twas the Night Before Layoffs,” it reads in part:

And far above it, in paneled repose,

The Secretary cackled, indifferent, composed…

‘Too slow, too global, too nuanced, too woke,

This place needs a purge, not another soft poke.’

Ben Franklin Fellows would tend to agree.

Whether one sides with Thomas-Greenfield or the Ben Franklin Fellows, one thing is certain: Effective diplomacy remains essential to American security. To deliver it, the State Department will need to reassert itself, clearly define its competitive advantage over other agencies, and improve its methods of delivery. That is now happening. Secretary Rubio is constructing a Department of State where groupthink is out and intellectual rigor is in; where DEI is replaced with merit; and where training focuses on winning in a tough world. He owes the nation nothing less.

David H. Rundell is a former Chief of Mission at the American Embassy in Riyadh and author of Vision or Mirage, Saudi Arabia at the Crossroads. Ambassador Michael Gfoeller is a former Political Advisor to the U.S Central Command and member of the Council on Foreign Relations. Together they have more than fifty years of diplomatic service. Both are members of the Ben Franklin Fellowship.

The views expressed in this article are the writers’ own.