The moral choice in war is ascertained by doing a crude calculus: Of the available options, which kills the fewest? The option of Japan suddenly embracing peace is an illusion. The brutal calculation was: Do we kill so many people by dropping atomic bombs or so many more by invading? Those were the only two choices.

I was boarding a plane at the Tokyo airport in the early ‘90s. A tall, elderly American man was immediately in front of me with his wife and a grandson. He turned to me and said, “Last time I was scheduled to come to Japan, the atomic bomb canceled the trip. Harry Truman saved my life!” He went on to explain how, in 1945, he was in training for the invasion of Japan. He expected to be killed. He was likely right.

I was boarding a plane at the Tokyo airport in the early ‘90s. A tall, elderly American man was immediately in front of me with his wife and a grandson. He turned to me and said, “Last time I was scheduled to come to Japan, the atomic bomb canceled the trip. Harry Truman saved my life!” He went on to explain how, in 1945, he was in training for the invasion of Japan. He expected to be killed. He was likely right.

In Okinawa, the closest US forces came to fighting on Japan’s home turf, the Japanese had a little over 100,000 soldiers and inflicted over 49,000 US casualties (about 12,500 killed). Thus, they inflicted a ratio of nearly 2:1, their forces to US casualties. With over 2,000,000 soldiers in mainland Japan, at the same ratio, without relying on guestimates, US casualties for “Operation Downfall” (the invasion of Japan) could have been 1,000,000, about a quarter of whom would have been KIA; that is about 250,000 dead Americans. That is, there could be a quarter-million US graves in Japan today if the invasion had been launched. Since the Japanese would have been fighting on their mainland, they could have been even fiercer than in Okinawa and thrown their civilians into the fray, as they were planning to do. They had accurately predicted the US strategy for the invasion of Kyūshū, devising their own Operation Ketsugō for an all-out defense. The invasion of Japan, if it had been necessary, could have been the bloodiest part of World War II, by far.

Those who oppose the atomic bombings argue that Japan was on the verge of surrender. Such fantasies don’t grapple with the reality of Japanese resolve and culture. The imperialist Japanese saw surrender as shameful. This was so ingrained into their culture that some Japanese soldiers kept hiding and even fighting for years after the war, with Second Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda continuing his guerrilla warfare in the Philippines until 1974. He would not surrender until his former commanding officer came to rescind his original orders. Even after the atomic bombs, with the prospect, as far as Japan knew, of more Japanese cities disappearing under mushroom clouds, and the invasion of the Soviet Union into Manchuria, eyeing northern Japan, still the Japanese war cabinet—the “Supreme Council for the Direction of the War”—voted 3 to 3 on surrender. Imagine, some want us to believe that Japan was on the cusp of surrender without the atomic bombs when, in reality, they only surrendered due to the emperor’s breaking a tie, after two atomic bombs and an attack from the Soviet Union.

Historian Stephen Ambrose debunks the idea that Japan could be reasoned into laying down its arms:

The Japanese government was by no means rational or ready to surrender. There were logical, sensible people in Japan, but they were not allowed a say in decision making. No scientist, professor, lawyer, nor even politician had an influence. They were dictated to by Hirohito and the military, who believed they could inflict enough casualties to force the Americans to negotiate. . .. They were ready to fight to the last Japanese. They were training women and children in the use of sharpened bamboo stakes to meet the Marines at the beach. They were preparing the most elaborate defenses, using what they learned in Iwo Jima and Okinawa. They had hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of kamikaze planes, hidden in caves or in forests. They had kamikaze powerboats, loaded with explosives, ready to hit the American fleet. They had men trained with explosive backpacks ready to crawl under American tanks. To surrender on American terms would be a humiliation for the Japanese military, who were pledged to fight for the Emperor to the last man. They were ready to sacrifice the whole nation to preserve their personal honor.

Still, those arguing against the atomic bombings will claim, as if a matter of dogma, that targeting civilians is always wrong, even if it achieved the hasty end of the war. Tucker Carlson claims this. First, the Japanese military industry, according to historian Victor Davis Hanson, was distributed in civilian neighborhoods. That is, rather than military production being set apart distinctly, it was suffused throughout cities. There was no way to strike the industrial base supporting the Japanese war effort without inadvertently hitting civilians.

Second, the ideology is simply wrong. Wars are not military vs. military conflicts detached from their nations. Wars are nation vs. nation. While the intentional targeting of non-combatants is wrong because it foolishly squanders limited military resources by hitting the part of the enemy nation that is not directly threatening it, when they are lost in an attack on the enemy nation’s military, it is the inherent tragedy of war. That is, killing civilians for no military goal is pure bloodlust, thus evil. But the idea that wars can be antiseptically pure, only involving militaries, is childishly unrealistic.

Finally, civilians were going to die either way. As we’ve seen, Japanese civilians were being prepared to sacrifice themselves in mass, often in futile attempts. Additionally, there was the ongoing loss of civilian lives in the countries Japan occupied, especially China. According to Victor Davis Hanson, by 1945, the Japanese army was killing 250,000 Chinese civilians every month. Also, US POWs were being killed. If the US had chosen not to drop the atomic bombs and opted to invade Japan in November 1945, about a million Chinese civilians would have died just in the interim. How many more civilians and prisoners would have been lost as the war ground on, we can only guess. As Eugene Sledge, a main source for HBO’s The Pacific, wrote, “The A-bombs saved my life, saved my buddies’ lives, and most decidedly saved the lives of millions of Japanese, civilian as well as military” (China Marine, xiv.)

There was no option in which large numbers of civilians would not get killed. Indeed, of the available options, the atomic bombings almost certainly produced the least civilian deaths. And they ended the war.

The moral choice is not arrived at by philosophically following an ideological theory. It must take in the practical realities, in this case, the final body count. The moral choice in war is ascertained by doing a crude calculus: Of the available options, which kills the fewest? The option of Japan suddenly embracing peace, fashioning its shin guntō swords into plowshares, is an illusion. The brutal calculation was: Do we kill so many people by dropping atomic bombs or so many more by invading? Those were the only two choices.

Yeo Tao Watt was rounded up by Japanese forces in early 1942, along with other Chinese men in Singapore, and marched to the beach. He wasn’t an insurgent or criminal, just a random Chinese man caught up in a dragnet. He sensed something was wrong, straggled behind, and when he saw an opportunity, ducked into the jungle and got away. About 70,000 others did not. They were machine-gunned to death. Like that American man I met in the Tokyo airport nearly 50 years after the invasion that would likely have killed him, Yeo managed to leave a legacy, a legacy both would likely not have left if the Japanese had had their way.

His daughter is my wife.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

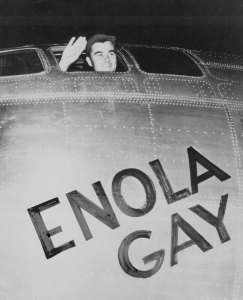

The featured image is “Colonel Paul Tibbets, pilot of the Enola Gay, waving from its cockpit. Photograph taken by soldier Armen Shamlian of the United States Army Air Forces (now the United States Air Force) in August, 1945 and now in custody of the US’s National Archives and Records Administration. (NWDNS-208-LU-13H-5) The image is in the public domain, as with most US federal government documents. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.