By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

This week, the government sold $724 billion in Treasury securities spread over 10 auctions, held on four days. Of these sales, $505 billion were bills with maturities from 4 weeks to 52 weeks, including $100 billion of 4-week bills; and $219 billion were notes and bonds, including a somewhat rough auction of 10-year notes and what was called an “ugly” auction of 30-year bonds.

Type

Auction date

Billion $

Bills 13-week

Aug-4

86.6

Bills 17-week

Aug-6

65.2

Bills 26-week

Aug-4

77.1

Bills 4-week

Aug-7

100.3

Bills 52-week

Aug-5

52.8

Bills 6-week

Aug-5

89.7

Bills 8-week

Aug-7

85.2

Bills

556.8

Notes 3-year

Aug-5

77.7

Notes 10-year

Aug-6

56.3

Bonds 30-year

Aug-7

33.5

Notes & bonds

167.4

Total auction sales

724.2

This is the Mississippi River of debt, as we’ve come to call the massive flow of hundreds of billions of dollars sold at auctions every week that the market has to absorb.

This heavy skew toward T-bills puts a lot more T-bills out there that then mature constantly since they’re so short term (between 1 month and 12 months). All these maturing T-bills will have to be refinanced, on top of the issuance needed to fund the ongoing deficits with new T-bills. So the already huge T-bill auctions will become gigantic.

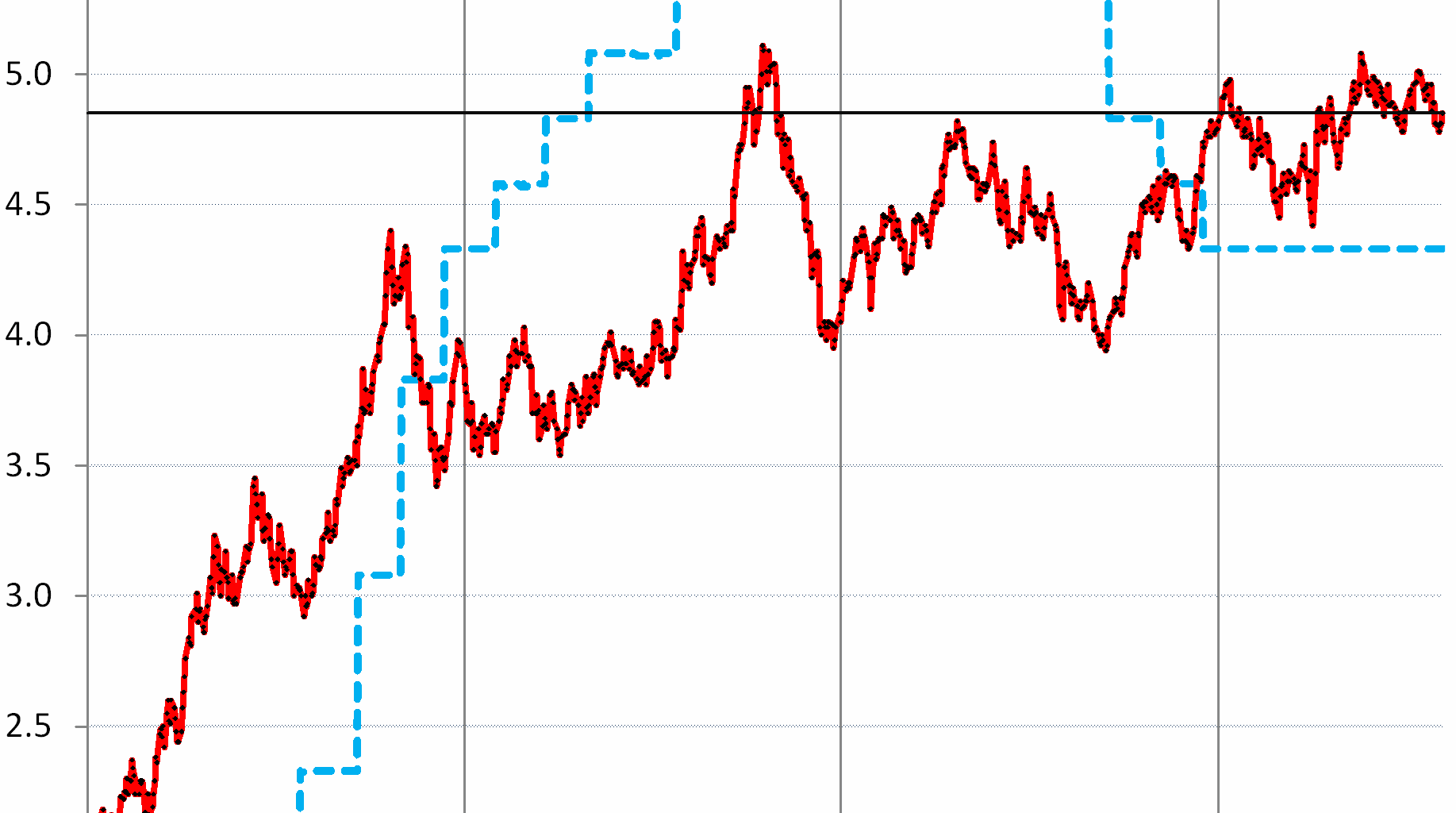

Despite the heavy skew toward T-bill issuance to take pressure off long-term yields, the 10-year yield rose by 7 basis points over the past four days to 4.29% today.

The 30-year yield rose by 9 basis points over the past four days to 4.85% today. It has been nervously clinging to the upper portion of the range of the past three years.

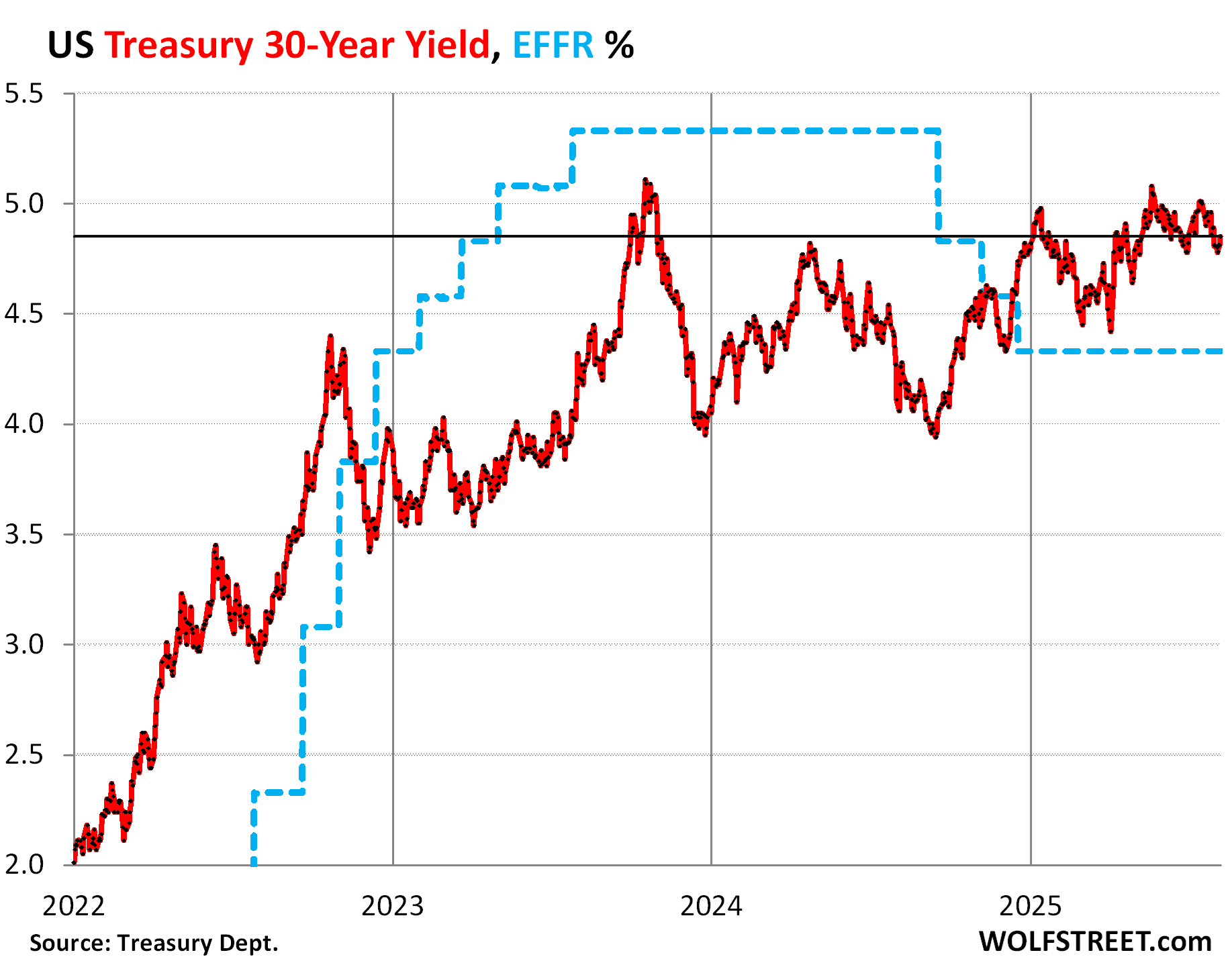

Recklessly ballooning federal debt hits $37 trillion.

Some of this new issuance replaced maturing debt and did therefore not add to the US government debt. The rest funded the new deficits and helped refill the government’s checking account, the Treasury General Account (TGA) at the New York Fed, which had been drawn down substantially during the debt ceiling period. That portion of the issuance increases the US government debt.

Some of the bills that were sold this week were then “issued” this week and became part of the overall debt. The remaining bills will be issued next week, and the notes and bonds sold this week will also be issued next week, and they will be added to the overall debt next week.

The total debt by the federal government jumped to $37.0 trillion (to be precise: $36.996 trillion), as of Thursday evening and reported Friday evening by the Treasury Department. It doesn’t yet include the portion of the securities that were sold this week but will be issued next week.

In a little over a month since the Debt Ceiling, the debt has spiked by $780 billion.

The flat parts in the chart reflect the periods of the Debt Ceiling – or, as the illustrious WOLF STREET commentariat said so poignantly, the “new debt floor.”

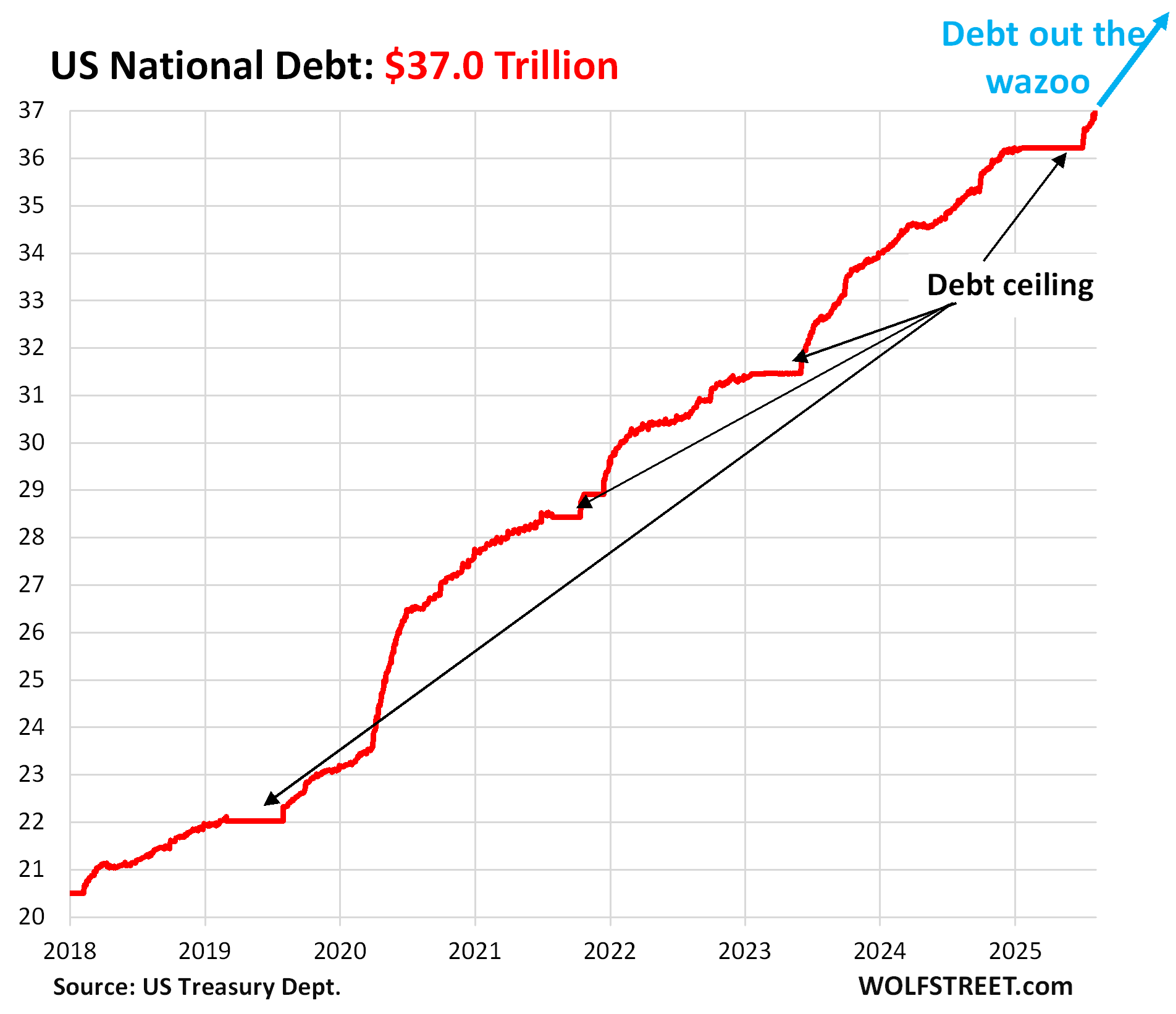

Refilling the TGA.

This additional $780 billion in new debt since the Debt Ceiling was used in part to fund the deficits, and in part to refill the government’s checking account, the Treasury General Account.

The TGA bottomed out at $260 billion on June 12. Then came a flood of quarterly estimated taxes due on June 15, plus the new tariffs that pumped an additional $20 billion a month into the TGA account.

And before the TGA had a chance to drain further, Congress lifted the debt ceiling. And since then, the TGA has risen by $178 billion and now holds $492 billion, according to the Treasury Department today.

The desired level of the TGA is $850 billion by the end of September, according to the Treasury Department. So roughly $350 billion in new issuance more to go to refill it, on top of the new issuances needed to fund the ongoing deficits, and on top of the issuance needed to refinance the maturing debt.

T-bills and the Fed.

The Fed has for a long time been discussing – including most recently Fed governor Waller who is angling for the chairman job – how it wants to shift the composition of its $6.6 trillion balance sheet toward T-bills.

It wants to get rid of its $2.1 trillion in MBS entirely, which could include the outright sale of MBS to speed up the process. And it wants to reduce in a big way its $4.2 trillion in Treasury notes, bonds, and TIPS, even as QT continues.

With this shift, the Fed would absorb over time $3-4 trillion in T-bills and in return throw $3-4 trillion of MBS and Treasury notes, bonds, and TIPS at the market that the market will have to absorb. That massive shift from long-term to short-term securities by the Fed would normally push up long-term yields and cause all kinds of problems in the bond market.

There are currently only $6 trillion in T-bills outstanding, and if the Fed needs $3-4 trillion in T-bills over time, there aren’t nearly enough T-bills outstanding for the Fed to shift into T-bills. So the Treasury department has started to issue a lot more T-bills so that the Fed can shift into them.

At the same time, as the Fed shifts its long-term securities into the market, the Treasury Department is not increasing by much the issuance of long-term securities, so that the market doesn’t get flooded with long-term securities from both directions.

The Treasury Department and the Fed – perhaps at Powell’s and Bessent’s weekly breakfasts – are clearly coordinating these massive multi-trillion-dollar shifts, and they will have to coordinate them before the Fed even starts shifting from long-term securities to T-bills, or else there are going to be some fireworks in the bond market.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

WOLF STREET FEATURE: Daily Market Insights by Chris Vermeulen, Chief Investment Officer, TheTechnicalTraders.com.