As morning broke in Zurich on Thursday morning, the usual sense of calm reigned. Staff cleaned the windows of the upmarket retailers lining the Bahnhofstrasse while gardeners watered the plants along the banks of the Limmat river.

Chino-clad city commuters breezed by on their bicycles and the gentle hum of traffic was only occasionally interrupted by the roar of a supercar — a reminder that Switzerland is considered, on many measures, to be one of the wealthiest nations in the world.

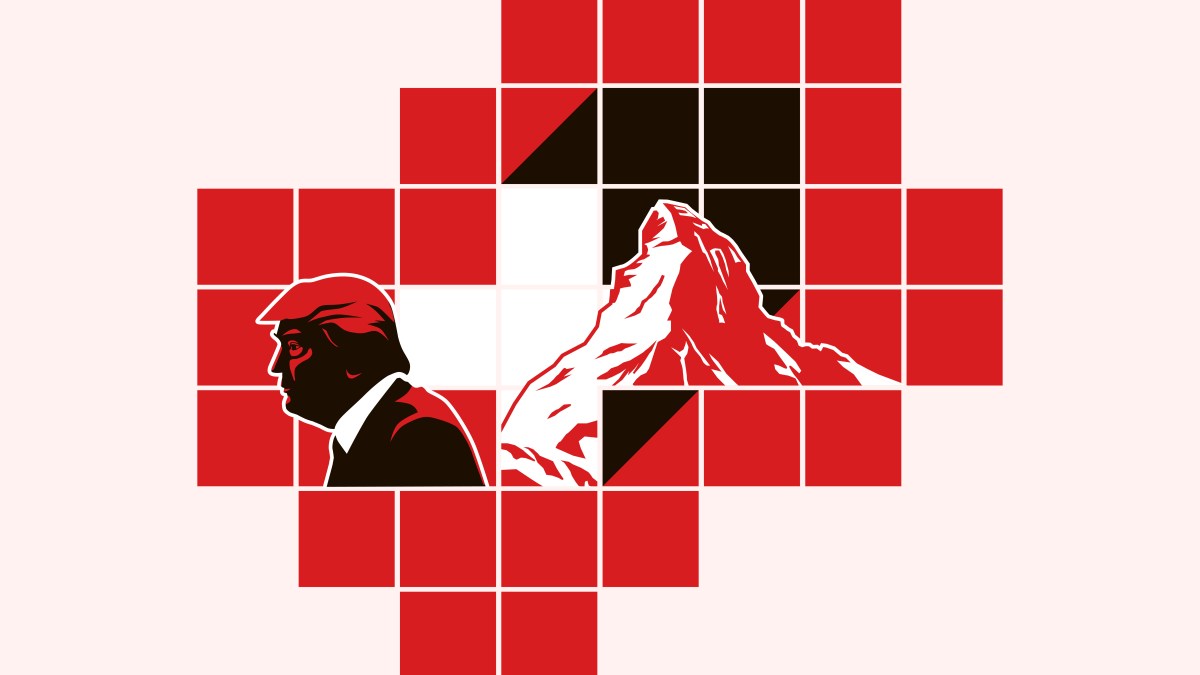

About 90 miles south, President Keller-Sutter and a delegation including Guy Parmelin, the economy minister, had just arrived back in Bern after failing to secure a trade deal with President Trump. As of that morning, a vast range of Swiss exports to the United States became subject to punitive 39 per cent tariffs, the biggest tariff in Europe and among the highest in the world. Pharmaceuticals and gold, two of the biggest Swiss exports, were spared. For now, at least.

• From Taco to Waco — is Trump’s tariff strategy paying off?

Right up until the final hour, Swiss business leaders had remained hopeful that a deal would be struck. By Thursday morning, hope was replaced with fury.

‘Shock and disbelief’

Jean-Philippe Kohl, deputy director of Swissmem, a trade body representing 1,400 industrial manufacturers in Switzerland, said there was “shock and disbelief”, adding: “This is very unfair… there is no rationality.”

Trump’s rationale is widely thought to be that a heavy tariff compensates for Switzerland’s trade surplus with the US, which stood at $47.4 billion in 2024. If service industries are included, the figure more than halves to $22 billion.

“It was astonishing that we got such a high tariff because, firstly, we have no industrial tariffs,” said Kohl, meaning that Switzerland does not levy a charge on industrial imports. “The second thing is Switzerland is a medium-sized economy but we are the sixth largest direct investor in the US.” He added that Swiss companies were responsible for 400,000 jobs in America.

Kohl said Swissmem members, which include small companies and also global names including ABB, the electrical engineering company, and Stadler, the train-maker, were already negotiating with American clients over the new levies.

“In the medium run, if we assume that this 39 per cent tariff will continue, we expect that to be the de-facto death of the export business of our industry to the US,” Kohl said. Economiesuisse, the largest association of Swiss businesses, suggests the punitive tariff regime could lead to 10,000 job losses across Switzerland.

• Profits halved at tariff-hit Jaguar Land Rover

It’s easier said than done to turn off American exports, however, particularly for companies that rely heavily on US business. Among them is Thermoplan, a maker of coffee machines that has held the contract to supply the machines used in Starbucks branches around the world for 26 years. It had sales of CHF355 million (about £327 million) last year and employs 544 people, most of whom work at its headquarters in Weggis, an hour’s drive south of Zurich. Almost a third of Thermoplan’s sales are to companies in the US.

Adrian Steiner, chief executive and co-owner of Thermoplan, said he was working on strategies to deal with “the crisis”, but added that it was difficult to move manufacturing outside Switzerland. “Eighty-two per cent of our components are sourced in Switzerland because of the quality and reliability and so to move this to another country, or especially to a new continent, is very challenging.”

Thermoplan may move some manufacturing to Germany, where it has a smaller subsidiary and from where US export tariffs are a more palatable 15 per cent. Establishing a US manufacturing hub is not out of the question, but would take two years. Is it worth planning for this when things are still in flux? Possibly not, Steiner conceded. “We don’t know what will happen in two days, let alone two years,” he said.

After their return to Bern on Thursday, Keller-Sutter and Parmelin held an extraordinary meeting with other ministers. The Swiss parliament operates on a collegiate principle. This means that power is shared among several individuals rather than concentrated in a single leader. This structure is designed to limit the potential for the excessive concentration of power and means consensus must be reached among all five of the ministers representing the main parties. This system is being blamed, in part, for the inability to reach a deal with Trump, who was said to be on the verge of signing a more favourable pact in July.

Breitling may raise prices

“Our president cannot decide on the phone in 20 minutes, like Mr Trump can,” said Georges Kern, chief executive of Breitling, the luxury watchmaker. Sales to the US account for 23 per cent of its turnover, which stood at CHF870 million in 2023. “We have a structural political issue and things take time,” Kern said, adding that the Swiss tendency to be overly measured may have worked against the nation in its negotiations.

Georges Kern, the chief executive of Breitling, says: “Sometimes you have to adjust to the people you’re facing”

ANTHONY KWAN/BLOOMBERG VIA GETTY IMAGES

“The Swiss people are perhaps too polite,” Kern said. “Swiss people are very rational and sometimes you need to also argue on an emotional level; perhaps we haven’t been emotional enough in our argumentation in that trade discussion … Sometimes you have to adjust to the people you’re facing.”

Like all of the Swiss leaders The Sunday Times spoke to, Kern did not hold Keller-Sutter personally responsible for talks breaking down and remained hopeful that a more appealing deal could be struck.

Yet he warned the company may have to put through price increases “not only in the US but in the rest of the world”.

He suggested that price hikes could affect the higher end of his product range. “There are some price points where we can increase more than others. At entry price point, we cannot increase that much. Unlike the high price points [where] it’s like the car industry – the high-end luxury car manufacturers have huge pricing power. We have certain pricing power, but it also has its limitations,” said Kerns.

Breitling has stockpiled three months’ worth of its watches in US warehouses ahead of the tariffs. He added: “Relocating production… is challenging due to the ‘Swiss Made’ label and the extensive watchmaking expertise concentrated here in Switzerland.”

Models such as the Navitimer and Chronomat are thought to contain about 200 to 300 individual parts, including not just big components such as the case, dial, hands, and movement plates, but also tiny screws and levers. Entry-level prices start at about £3,700.

Kerns said he was keeping calm in the face of the disruption. “Panic is the worst state of mind you can have in such a situation,” he said.

Customers cancel orders

Nonetheless, the tariffs have had an immediate impact on some businesses. Among them is Netstal, a maker of high-precision injection-moulding machines used in food, drink and pharmaceutical packaging. Speaking from near Cincinnati, where the company has a small sales outpost, Renzo Davatz, chief executive of Netstal, said he had already received a phone call from a key US customer asking to halt their order.

“His machine was ready to be sent out this week… This customer said, ‘I’m not in a position to pay 39 per cent more. Please stop the truck, cancel the ship and [store] the machine until there is more clarity’.”

This brings its own challenges: with the machines weighing between ten and 30 tonnes, they take up a huge amount of storage and containers on ships are booked for forthcoming order dispatches.

For Netstal, where exports accounted for 95 per cent of its €220 million revenues in 2023, a focus on US growth is now likely to shift to different parts of the world. Davatz said his teams would refocus to “better support our teams in Mexico or Brazil”.

Another business trying to find solutions is Maurice de Mauriac, a family-owned watchmaker based in Zurich. About 30 per cent of the sales of its watches, which start at CHF2,000, are to American customers, many of whom visit the atelier in the city’s financial district.

Brothers Leonard, right, and Massimo Dreifuss of Maurice de Mauriac in their watch shop in Zurich

RAJA LÄUBLI

Online accounts for about a tenth of sales. The company has refrained from raising prices for American customers buying through the website, for now. “Trump can change his mind one day to another. So hopefully he will change his mind,” Leonard Dreifuss, a director of MDM, said. If the company does need to put through price increases, it says it will most likely share the burden 50-50 with customers.

A waiting game

Also playing the waiting game is Ginny Litscher, an artist and clothes designer who initially established her business in London before moving back to Zurich eight years ago. She is preparing a collection for London Fashion Week and is collaborating with the French luxury brand Lalique to sell a range of scarves with prices ranging from £310 to £395.

“I’m just sitting it out at the moment,” Litscher said. “I don’t think this is the last of it. I see it as a negotiating tactic and in the end there will be a solution.”

Ginny Litscher says she will add the export levy to her shipping fees

RAJA LÄUBLI

Litscher said the debacle had been “shocking” to Swiss people because it went against the very “organised” nature of everything. “They’re not used to it. They’re freaking out.”

She said she would add the export levy to her shipping fees. “Then it’s their decision if they want to pay for it.”

Such decisions add weight to the theory that the American consumers will end up bearing the brunt of Trump’s tariffs. Jan Atteslander, a member of the executive board at Economiesuisse, said the “unjustifiable” 39 per cent levy was “not in the interests at all of the US economy”. He said: “Tariffs are never a good idea and it’s always the importing country that pays dearly.”

Ultimately, the row could force the Swiss to move closer to the European Union. While the US represents the largest export market by country, accounting for CHF65.3 billion in 2024, taken together, Europe and the UK equate to nearly twice that, Mathias Hoffmann, professor of international trade and finance in the department of economics at the University of Zurich, said.

The Switzerland-EU framework agreement has been through various iterations since 2021 and is waiting to be ratified. The need to get a deal in place had gained a new sense of urgency, he said. “We see with Trump what happens when we are on our own. And there’s this huge market on our doorstep.”