In August 1996, within just three days, two Greek Cypriots—24-year-old Tassos Isaac and his cousin, 26-year-old Solomos Solomou—were killed in the UN-controlled buffer zone near the town of Deryneia, in the Famagusta district. Both murders were carried out in plain view, both blamed on Turkish soldiers and members of the ultranationalist Turkish group known as the Grey Wolves.

The events would shock the island, galvanise international outrage, and shed a harsh light on the lawless violence festering along the “Green Line”—the military demarcation that has split Cyprus since Turkey’s invasion in 1974.

A protest turns deadly

On 11 August 1996, hundreds of motorcyclists from across Europe had gathered in Cyprus for an anti-occupation rally. Their original plan—to ride to the occupied city of Kyrenia—had been called off under government pressure to avoid confrontation. But many demonstrators, defying the decision, pushed on toward the UN buffer zone in Deryneia, confronting Turkish troops and paramilitaries head-on.

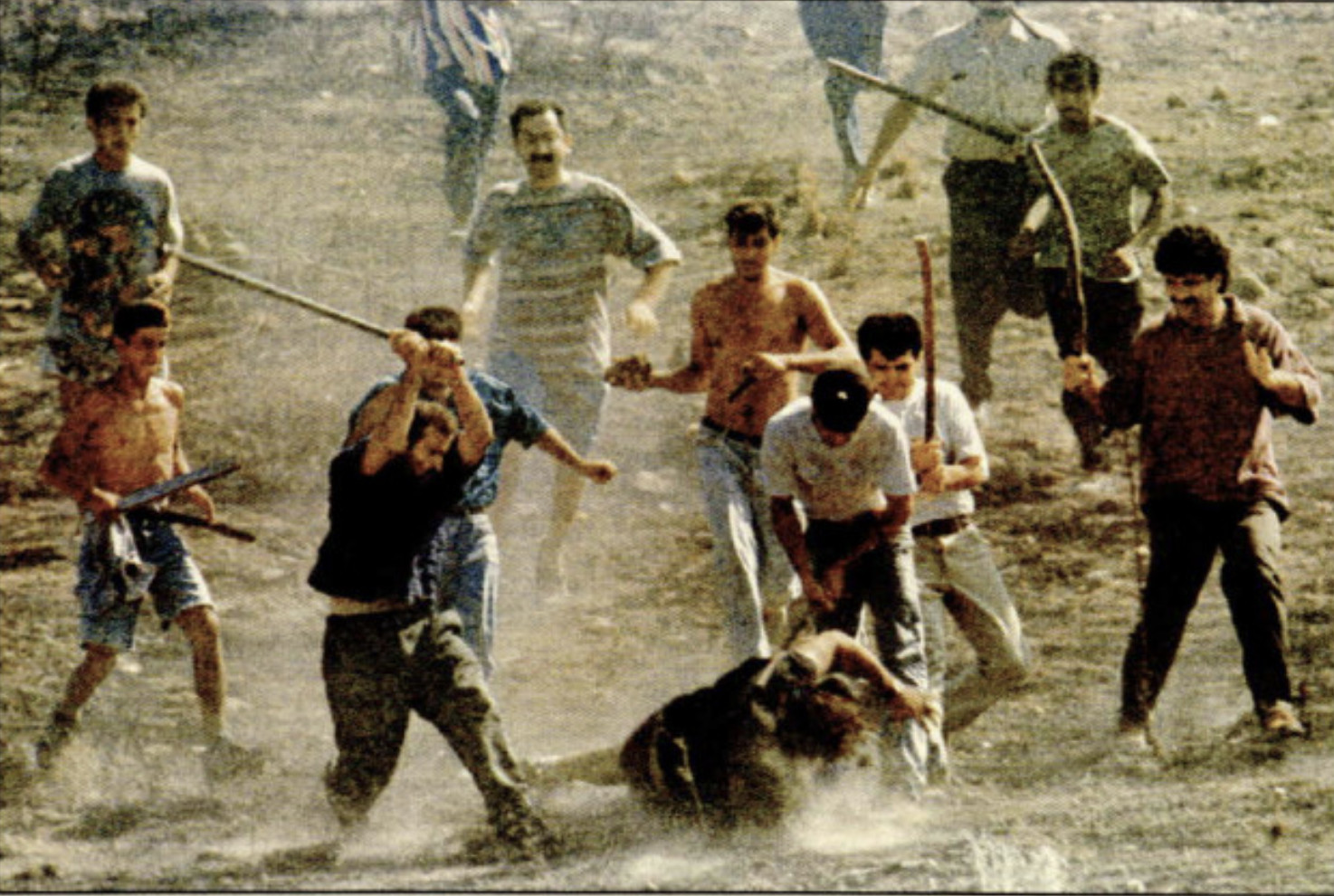

What began as a peaceful demonstration quickly turned into chaos. According to Greek daily TA NEA at the time, “Turkish soldiers and paramilitaries attacked the unarmed Cypriots with unprecedented barbarity—using live and plastic bullets, iron bars, clubs, and stones.”

Isaac was caught in the coils of barbed wire, unable to break free. Witnesses say members of the Grey Wolves set upon him, beating and kicking him until he lay lifeless. UN peacekeepers, present at the scene, have long been criticised for failing to intervene.

In a detail that still haunts Cyprus, Isaac had managed to escape the wire moments earlier but returned to help other trapped protesters—only to be surrounded and killed.

A funeral and a second killing

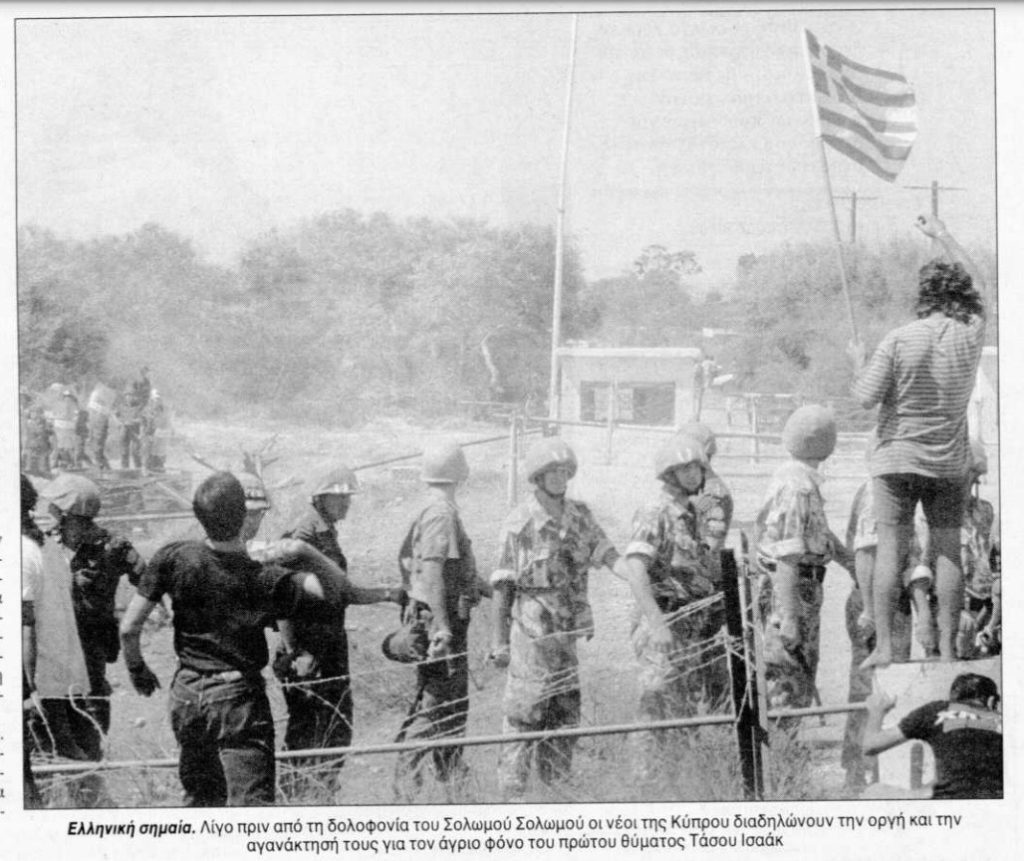

Three days later, on 14 August, Isaac’s funeral took place in the town of Paralimni. Among the mourners was his cousin, Solomos Solomou. After the service, a group of young men returned to the Deryneia crossing to lay flowers where Isaac had been killed.

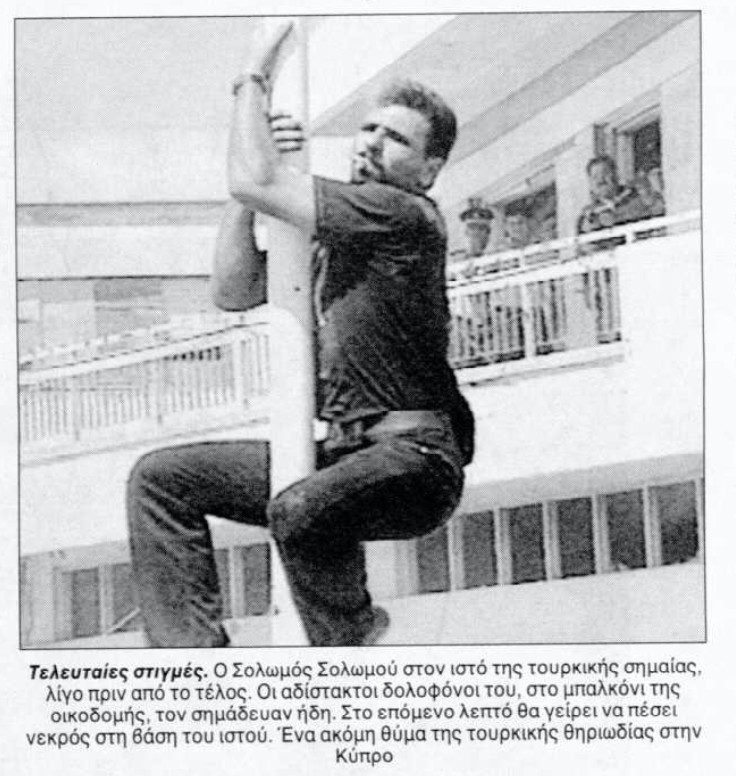

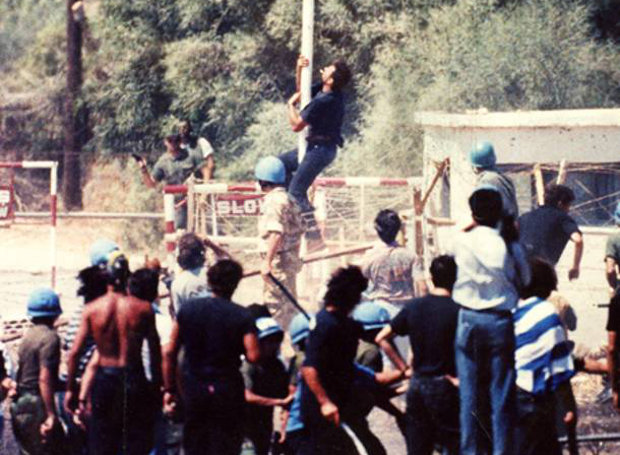

Television cameras were rolling as Solomou, cigarette in mouth, slipped past his friends and UN troops, heading toward a Turkish flagpole on the edge of the occupied zone. His intent seemed clear: to climb the mast and remove the flag—a defiant gesture against the occupation.

Seconds later, shots rang out. Three bullets struck him—one in the neck, one in the mouth, one in the stomach. He fell instantly. The footage of his killing, broadcast worldwide, turned Solomou into an enduring symbol of resistance for Greek Cypriots.

The gunfire wounded 11 others, including two UN peacekeepers and a 60-year-old woman who had come to the area simply to find her son. She was shot from a distance of 600 metres, in territory under the control of the Republic of Cyprus.

The face of the killers

Cypriot authorities later identified Solomou’s shooter as Kenan Akın—a Turkish settler from mainland Turkey, a former Turkish army officer, then serving as a “minister” in the unrecognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, and an agent of Turkish intelligence.

International arrest warrants were issued against Akın and several others for the murders of both Isaac and Solomou. None have ever been executed.

Both killings were linked to the Grey Wolves, a far-right Turkish ultranationalist organisation founded in the late 1960s by Alparslan Türkeş. The group has been implicated in political assassinations inside Turkey, cross-border violence, and organised crime, including drug and arms trafficking. Reports at the time alleged that Grey Wolves members had been flown into Cyprus in August 1996, funded by Turkey’s then-foreign minister Tansu Çiller.

The political faultline

The murders underscored the fragility of peace along the UN buffer zone—known locally as the “Green Line”—the last dividing line of its kind in Europe. It runs 180 kilometres across the island, separating the internationally recognised Republic of Cyprus in the south from the Turkish-occupied north.

Deryneia itself lies just a few hundred metres from the abandoned city of Varosha, a fenced-off “ghost town” sealed since 1974. The backdrop of derelict hotels and barbed wire made the killings feel like an echo from another era—yet they were very much a product of the tensions that still simmer.

The UN’s inaction during both incidents became a source of bitter criticism in Cyprus, fuelling accusations that peacekeepers were unwilling—or unable—to protect civilians from violence in the buffer zone.

A long shadow

For Greek Cypriots, Isaac and Solomou’s deaths remain potent symbols of sacrifice in the face of occupation. Their funerals drew crowds in the tens of thousands, and their names are still invoked at memorials and protests.

The international profile of the killings also forced uncomfortable attention onto the Grey Wolves, whose extremist ideology and violent track record had often been overlooked in Western capitals.

Even decades later, the names resurface in unexpected ways. In February 2023, Kenan Akın—still wanted in Cyprus—was once again in the headlines. This time, it was for personal tragedy: his two grandsons, Doruk and Alp Akın, were killed in the collapse of a hotel during the massive earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria, claiming more than 50,000 lives.

A tragedy remembered

The murders of Tassos Isaac and Solomos Solomou remain unsolved crimes in the eyes of Cypriot justice. But for many on the island, the greater injustice is that they were allowed to happen in full daylight, under the supposed watch of the international community.

Nearly 30 years on, the grainy footage still shocks: a young man caught in barbed wire, beaten to death; another, cigarette in his mouth, climbing a flagpole before being felled by bullets. They are moments that capture the enduring human cost of Cyprus’s division—a cost still measured in lives, lost futures, and the uneasy silence of the Green Line.