For years, the talk in boardrooms and investor presentations has been about “discipline” and “capital efficiency.” These are the code words for a strategy that keeps production largely flat, trims high-risk exploration budgets, and returns more cash to shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks. The era of endlessly chasing production growth at any cost is over, replaced by an approach that seeks to manage fossil fuel portfolios like mature, declining assets.

The optics are powerful. European majors like BP and Shell speak of winding down oil output over the coming decades. U.S. giants such as ExxonMobil and Chevron, while less explicit about decline, focus their messaging on shareholder returns rather than aggressive expansion. In theory, this suggests an industry willing to accept that oil demand will peak within a decade or so, and to manage the retreat in a way that rewards investors.

But this managed decline narrative tells only half the story.

Maximising the Present

Behind the scenes, oil majors are working hard to squeeze every last drop of value from their existing resource base. In the United States, ExxonMobil’s consolidation of Permian Basin acreage and Chevron’s acquisition of Hess are both moves aimed at securing long-life, low-cost barrels that will remain profitable even in a lower-price environment. These assets allow companies to keep cash flowing for decades, even if global oil demand starts to plateau.

Related: Syria Eyes Pipeline Lifeline as Post-Assad Power Struggle Escalates

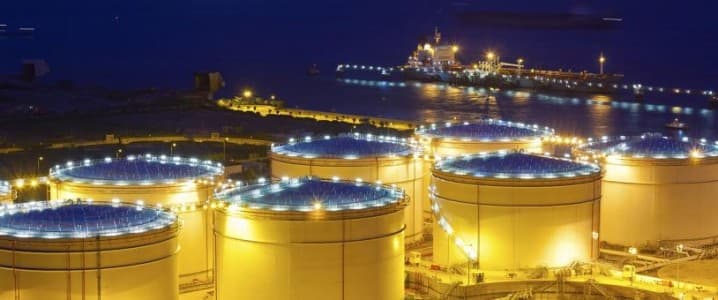

Elsewhere, offshore developments in Guyana, Brazil, and the Gulf of Mexico are proceeding at full speed. These projects were sanctioned in the high-price years and are now coming online just as costs stabilise, offering highly competitive returns. LNG investments, from Qatar to Mozambique to the U.S. Gulf Coast, are being expanded on the logic that gas demand will remain robust well into the 2040s.

In other words, even as the public relations machinery focuses on energy transition and managed decline, the operational machinery is set firmly on maximising fossil fuel output from the best available assets.

Quiet Moves into Alternatives

This does not mean oil companies are ignoring renewables entirely. Far from it. The same balance sheets that finance oilfield expansions are also funding stakes in offshore wind farms, solar projects, hydrogen hubs, and biofuel plants. Shell has continued to invest in EV charging infrastructure in Europe and Asia. TotalEnergies has quietly built one of the largest solar portfolios among oil majors. BP, despite scaling back its renewables growth targets, still holds substantial wind capacity in the U.S. and the UK.

The difference is in tone and ambition. These investments are rarely centre stage in investor calls. They are treated as portfolio diversification rather than the core business of the future. In many cases, the return thresholds set for renewables are higher than those applied to oil and gas, which makes the sector look less attractive on paper. That, in turn, slows the pace of internal capital reallocation.

The Transition Talent Trap

Perhaps the most overlooked asset in the oil majors’ arsenal is not their capital, but their human capital. The industry employs tens of thousands of engineers, project managers, logistics specialists, and technical experts capable of delivering multi-billion-dollar projects on time and on budget in some of the most challenging environments on earth.

This capability is exactly what is needed to scale low-carbon technologies such as green hydrogen, carbon capture, and advanced grid infrastructure. Yet most of this talent remains focused on extending the life of oilfields, optimising refinery margins, and delivering incremental production gains.

It is not that the industry lacks the skills for the energy transition, it is that it has not made a deliberate, strategic decision to deploy those skills at scale. Instead, renewables divisions remain small, often siloed from the main corporate structure, and sometimes treated as experimental ventures rather than mission-critical operations.

Strategic Myopia

The reluctance to go all-in on transition is understandable from a narrow business perspective. Oil remains highly profitable, especially from low-cost fields. Shareholders reward cash flow discipline and dividends, not long-term capital bets that may take decades to pay off. And politically, the energy transition remains uneven, making fossil fuel demand more resilient than many climate advocates once assumed.

But this caution carries a cost. If the oil majors wait until market and policy signals are overwhelming before shifting resources, they risk losing their ability to shape the transition on their own terms. By then, utilities, tech companies, and specialised clean energy developers may have captured the most lucrative opportunities, leaving oil companies with little choice but to follow rather than lead.

A Missed Leadership Opportunity

What is so frustrating for observers, and, quietly, for many inside the industry, is that the majors are uniquely positioned to lead a pragmatic, large-scale transition. They have global reach, deep project pipelines, and experience in integrating complex supply chains across continents. They know how to operate in politically unstable environments, manage large capital programs, and deliver infrastructure under pressure.

If even a portion of this expertise were redirected toward scaling renewables, improving energy storage, and building out hydrogen and carbon capture systems, the impact could be transformational. Oil majors could redefine themselves as energy companies in the fullest sense of the term, rather than oil companies dabbling in green ventures.

The Road Ahead

The age of managed decline is not, in itself, a problem. Oil demand will eventually level off, and managing that shift carefully is essential for both economic stability and energy security. The problem lies in the imbalance between managing decline and preparing for what comes next. Right now, the balance is tilted heavily toward maintaining the status quo for as long as possible, with the transition treated as a secondary project. However, the growth is in the transition.

Until oil majors choose to put the transition at the heart of their corporate strategy, they will remain reactive players in a game that is moving forward without them. The irony is that the same discipline and technical excellence that made them dominant in the age of oil could make them equally dominant in the age of low-carbon energy. But that will require a leap of vision, and a willingness to see leadership as something more than a well-managed exit.

By Leon Stille for Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com