The Russian invasion of Ukraine. The rise of Russian-style hybrid warfare. General receptivity to the idea of nonviolent civilian-based defense (CBD) in Latvia, one of the two Baltic states that share a border with Russia, has never been lower. It was the US Special Operations Forces (US-SOF) and NATO that succeeded in drawing the Latvian state’s attention back to CBD, presented as an integral part of national defense. The question of how to implement this concept, known as “comprehensive defense”, remains rather delicate in Latvia to this day – with the exception of a very convincing defense education project[1].

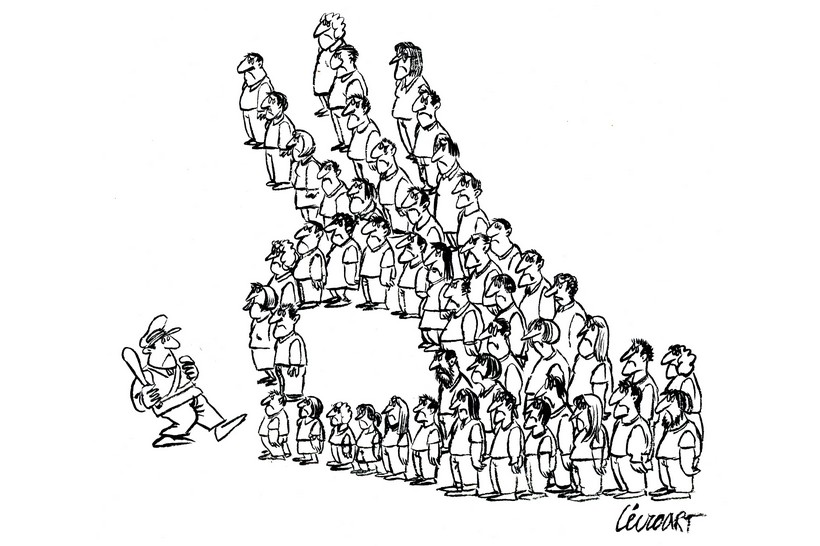

“Whole-of-society defense” is a military concept that emphasizes the broad participation of society in the defense of a national territory against influence, invasion and occupation. Able to coordinate resistance actions themselves – whether violent or not – civilians are seen as one of the responsible parties in national defense. In practice, comprehensive defense is based on cooperation between civilians and the armed forces, planned and coordinated by the state, the armed forces and the public. This distinguishes it from nonviolent civilian-based defense (CBD), which is a more organic, unarmed civilian initiative.

The US Special Operations Forces (US-SOF), a cross-cutting command founded in 1987 that enables the different branches of the US military to coordinate in joint operations, is responsible for exhausting all unarmed options to prevent the outbreak of armed conflict in foreign countries, according to a US-SOF advisor who, for operational reasons, wishes to remain anonymous. Nonviolent action is seen as having strategic merits in its own right, as an inexpensive “option” and particularly interesting for its intrinsic value as a deterrent.

It is considered an integral part of national defense, and therefore an auxiliary to armed operations. Indeed, nonviolent action serves to decentralize responsibility for defending a national territory.

It may seem surprising that the US-SOF encourages and advises the Latvian government to take advantage of nonviolent action. In fact, “nonviolent resistance has been part of US doctrine since the Second World War”, says my US source, clarifying that the references are mainly conceptual rather than operational terms. Why is this? Because it must be “led by civilians,” he specifies. “Civilian institutions are better placed to carry out strikes and civil disobedience. Occupation and, to some extent, subjugation require the obedience of the people,” explains my source, echoing our great thinkers on civil disobedience.

This article explores the nuances and tensions around CBD and comprehensive defense, the latter being more present today in Latvia, despite the extensive and successful practice of CBD there during the Soviet occupation. Despite the public’s lack of receptivity to all that is nonviolent at present, the Latvian government is logically preparing its people for CBD through “crisis preparation” programs. In particular, it has launched a very popular and convincing defense education program in high schools, inspired by comprehensive defense and incorporating certain elements of the nonviolent corpus.

“Crisis preparedness”

Latvia’s National Defense Law was amended in 2020-21 to indicate what civilians can do in terms of non-cooperation (but also in terms of armed action) in the event of occupation. In 2020, the Latvian Ministry of Defense published a brochure on its website entitled “What to do in the event of a crisis” (available in English, Latvian, Russian and Braille). The brochure explains the practical steps to be taken in the event of power cuts or other problems caused by “crises” such as natural disasters, pandemics and “military operations”. Reading the section on “Residents’ actions in the event of war”, one page is devoted to “resistance”, and we observe that nonviolent action by “residents” (acts of non-cooperation, strikes…) do not necessarily occupy a lesser place in the resistance toolbox than space occupied by armed action.

It has been rationalized and integrated.

No doubt because of their long history of CBD, the Latvian government seems convinced that it plays an important role in national defense—today more than ever in the face of Russian hybrid warfare. “Nonviolent resistance is a topic of discussion, and we’re looking to implement it even in military training,” confides my source at the Latvian Ministry of Defense, who wished to remain anonymous. However, given the Latvian experience during the Soviet occupation and the horrors we see in Ukraine, advocates of “nonviolent resistance” or a so-called “nonviolent civilian-based defense” campaign would probably be considered naive.

“People are more eager to learn how they can prepare and how they can support the army. They’re eager to get information about crisis preparedness. They are very patriotic and support military action. People are very connected and aware of what’s going on in Ukraine. They don’t think they can do anything with nonviolent resistance,” concludes my source.

For my part, I deduce that the government has simply found a new framework for CBD and its related concepts within comprehensive defense, which places nonviolent action and armed action on the same strategic plane. But even so, the methods of combating cyberwarfare and disinformation, the main features of Russian-style hybrid warfare, remain entirely nonviolent, as do the strikes and non-cooperation mentioned in the Ministry’s brochure.

Education and the spirit of defense

While the defense of culture and language against Soviet influence was a major concern in the past, the fight against Russian propaganda and the development of defense education and media literacy are current priorities for the Ministry of Defense. Cyberattacks, disinformation, propaganda… These hybrid warfare tactics have made Latvians realize that they need to double down on their efforts to introduce the spirit of defense and resilience into schools. And Latvian pupils are apparently keen to learn more about national defense in all its dimensions.

“We can really reach them as a target group,” my source tells me. “It’s harder to educate adults, especially the elderly, who are difficult to bring together physically. Plus, they already have their own life experiences and beliefs,” he continues.

Children bring home new knowledge, for example about the importance of participation in elections and media literacy, and are therefore a more promising group to target with educational initiatives on defense.

There are no programs (yet?) explicitly on nonviolent action as such, but the state’s defense program includes the history of local resistance (including nonviolent), cyberdefense strategies, “civic activism”, patriotism, critical thinking, adventure training, forest survival and winter survival. The program began as a pilot project in 2018 and is now mandatory for students in their junior or senior year. It consists of one one-day session per month.

The course has been very well-received by schools and students, according to my source. The program started with 12 schools, then 50 the following year, and has grown from there. The main challenge is to train enough instructors.

The strategic merits of nonviolent action

It’s hard to deny the effectiveness of nonviolent action when armed forces integrate it into their strategic doctrine and wartime training. It is nevertheless very provocative to completely instrumentalize nonviolent action and isolate it from moral issues, but the reality is that war and conflict will persist. We need to study nonviolent action in conjunction with armed action, as it manifests itself in the real world today.

Above all, defense education must not stop with military concepts; the nonviolent corpus enriches our resilience to modern political violence. Nonviolent action is an inexpensive, inclusive and effective way for people to defend democracy and freedom on their own … and it starts with education.

Select sources

Jacques Semelin, Jean-Marie Müller et Christian Mellon, La Dissuasion civile (Fondation pour les études de défense nationale), 1986.

Anika Binnendijk et Marta Kepe, Civilian-Based Resistance in the Baltic States, RAND Corporation, 1 novembre 2021. Consulté le 23 mars 2024.

« 72 HOURS: What to do in case of a crisis. » Ministère de la défense, République de Lettonie.

« Comprehensive State Defence ». Ministère de la défense, République de Lettonie.

Maciej Bartkowski, “An Activist’s Guide to Fighting Foreign Disinformation Warfare”, Minds of the Movement, novembre 2018, Centre international sur le conflit non violent.

La stratégie nationale intégrée du département d’État américain pour la Lettonie.

Interviews conducted by author

Notes

[1] This article was written by Amber French in a personal capacity. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the views of ICNC or IPP..

The Author

Amber French is an independent consultant. She is editor-in-chief of the journal Minds of the Movement (International Center for Nonviolent Conflict) and a research associate at the Institute for Peace (IPP). She co-founded the IPP working group on “Civil resistance, non-violence and the culture of peace”.

This article is part of the dossier on Civilian-Based Defence (CBD), issue 213 (special edition), December 2024, of the journal Alternatives non-violentes.

Articles from the dossier “Civilian-Based Defence (CBD)” published by Pressenza in French, German and English.