Defense Minister Ahn Gyu-back delivers a speech at a signing ceremony marking South Korea’s export of a second batch of K2 tanks to Poland, at Gliwice on Aug. 1. (Ministry of Defense)

Defense Minister Ahn Gyu-back delivers a speech at a signing ceremony marking South Korea’s export of a second batch of K2 tanks to Poland, at Gliwice on Aug. 1. (Ministry of Defense) As top 10 arms exporter, Seoul’s modern weapons soar globally, but guarding tech, talent remains challenge

It was 72 years ago that the bloody 1950–53 Korean War ended with an armistice.

Today, the once-war-ravaged nation stands among the world’s leading arms exporters, its factories turning out advanced tanks, artillery systems and fighter jets destined for battlefields far beyond the Korean Peninsula.

South Korea’s arms industry is riding a wave of global demand, but the current geopolitical climate brings both opportunity and risk. Its weapons are in high demand for their advanced technology and fast delivery, yet the country must tread carefully, as shifting alliances and regional tensions complicate the path forward.

Turning crisis into opportunity

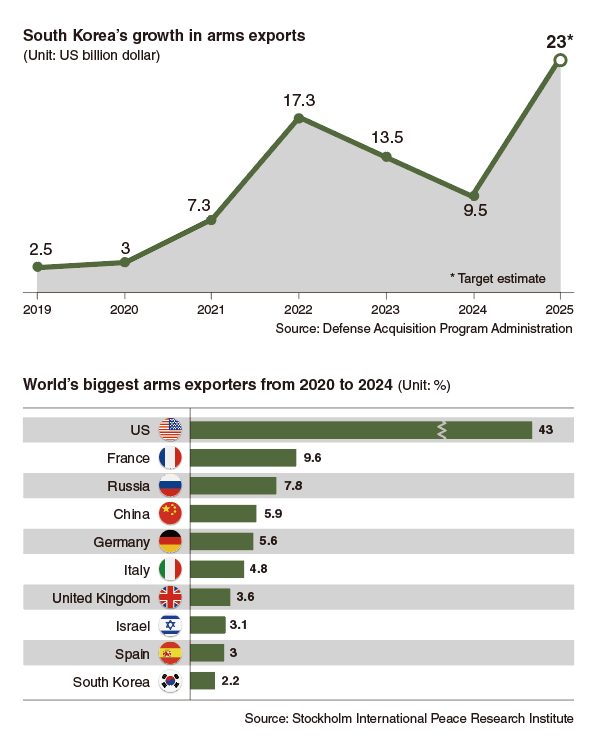

South Korea, in recent years, has often been listed among the world’s top 10 arms exporters, in the ranks with the United States, Russia and China. It was No. 10 among global arms exporters, with a 2.2 percent share of the market in the 2020-2024 period, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

The South Korean government is now setting its sights on breaking into the ranks of the world’s top four arms exporters.

“South Korea has rapidly matured into one of the world’s leading arms exporters, backed by a highly capable manufacturing base, proven platforms and a track record of delivering on time and at scale,” Yu Ji-hoon, a research fellow at the Korea Institute for Defense Analyses, told The Korea Herald.

Yet it took decades of sustained effort to get this far.

In 1971, the United States began withdrawing troops from South Korea, reducing the number of American soldiers stationed there, even as tensions with North Korea persisted in the decades after the Korean War. The withdrawal was carried out under the Richard Nixon administration, which pushed for allied nations to strengthen their own self-defense capabilities.

This prompted South Korea to concentrate its efforts on developing and producing advanced weaponry to achieve self-reliance in defense. In 1973, the government launched a full-scale initiative to promote the heavy and chemical industries, a critical component in manufacturing weapons, according to the Korea Development Institute.

The Russian arms repayment project, a unique post-Cold War arms-for-debt arrangement between Seoul and Moscow, which started in the late 1980s, was another driving force behind the South’s defense industry. Instead of cash repayments, Russia repaid part of the debt with military equipment and related technology.

Until the mid-2010s, South Korea’s arms exports were largely concentrated in ammunition, naval vessels and some aerospace components. But its export portfolio has since started to diversify and expand.

Provider of world-class weapons

In South Korea’s expanding arms export portfolio, the K2 tank, dubbed “Black Panther” and built by Hyundai Rotem, has been a flagship item. It first entered service with the military here in 2014.

The K2 is South Korea’s most advanced main battle tank, designed for speed, precision and adaptability on the mountainous Korean Peninsula. In recent years, it has drawn major international orders, most notably from Poland, as militaries seek modern armor to replace aging Cold War units.

Two FA-50GF fighter jets fly behind a MiG-29 aircraft. (Korea Aerospace Industries)

Two FA-50GF fighter jets fly behind a MiG-29 aircraft. (Korea Aerospace Industries) It is central to South Korea’s largest-ever defense export deals, including the one with Poland, signed in 2022,in which Warsaw ordered 180 K2 Black Panther tanks from Hyundai Rotem in a $3.37 billion agreement. Deliveries began within months, far faster than European or American suppliers could offer.

In 2025, Warsaw followed with a $6.5 billion contract for 180 upgraded K2PL tanks, to be produced in part in Poland. The two phases, part of a broader plan involving the manufacturing of up to 1,000 K2s, have made Seoul one of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s most important new arms partners and cemented South Korea’s status as a major player in the global defense market.

Other key weapons in the portfolio are the K239 Chunmoo Multiple Rocket Launcher System, K9 self-propelled howitzer, FA-50 fighter jets and Surion helicopters.

Prominent deals made with global clients include K239 Chunmoo MLRS systems purchased by the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia in 2017 and 2022, respectively.

South Korea on Thursday signed a $250 million agreement to supply Vietnam with 20 K9 self-propelled howitzers, marking the weapon’s first deployment to a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations bloc. The K9 is already in service in countries such as Turkey and Egypt.

Experts say South Korea’s growing appeal lies in its weapons’ balance of cost and capability — and in its ability to offer buyers comprehensive, tailor-made packages.

“South Korean-manufactured weapons, including the K9 self-propelled howitzer, offer proven performance, interoperability with Western systems and cost-effectiveness,” explained Yu, who is also a former professor of military strategy at the South Korea’s Naval Academy. “More importantly, Seoul has demonstrated willingness to localize production, transfer technology and support customers’ domestic capability development.”

South Korean arms-makers are increasingly structuring export deals to include technology transfers and licensed local production, allowing buyer nations to build part — or in some cases most — of the weapons on their soil. This approach not only sweetens contracts in competitive bidding, but it also aligns with many countries’ desire to develop their domestic defense industries. This is reflected in Hyundai Rotem’s Poland deal, as well as Hanwha Aerospace will establish joint production lines for the K9 howitzer and Chunmoo rocket system, with Romania and Poland, respectively.

“It’s a key all-in-one package deal strategy played out by South Korean arms manufacturers — providing technology transfer, customized weapons and factories for the buyers,” Choi Gi-il, a professor of military studies at Sangji University, said via phone.

Rosy future, lingering risks

South Korea’s arms exports fell to $9.5 billion last year after hitting a record high of $17.3 billion in 2022 and sliding to $13.5 billion in 2023, according to its arms procurement agency, the Defense Acquisition Program Administration. DAPA is cautiously eyeing a $23 billion goal for this year.

The agency’s ambitions may get a lift this year from favorable geopolitical winds, according to an expert. NATO allies have recently agreed to more than double their defense spending target from 2 percent of gross domestic product to 5 percent by 2035, creating a surge of demand for new equipment.

K9 self-propelled howitzer (Hanwha Aerospace)

K9 self-propelled howitzer (Hanwha Aerospace) Adding to the momentum, Seoul’s latest cooperation with Washington in the shipbuilding sector, under a joint initiative known as “Make American Shipbuilding Great Again,” is expected to further bolster South Korea’s defense export prospects. Seoul has put forward sweeping proposals for joint shipbuilding projects with the US, a move that was reportedly pivotal in securing a tariff agreement with the administration of US President Donald Trump earlier this month.

“Overall, South Korea’s defense industry is likely to get a lift this year from NATO’s increase in defense spending target and Seoul’s role in building American ships, as well as cooperation on maintenance, repair and overhaul projects for the sector,” Choi of Sangji University said.

Choi added that South Korea’s existing top clients are likely to continue to make steady purchases.

“Looking at global arms exports by region, the most prominent markets include Eastern European countries facing wartime conditions and Middle Eastern nations, where unstable security situations are driving demand,” he noted.

However, the new momentum carries its own risks.

“The global trend right now resembles Trump’s reshoring policy, aimed at bringing manufacturing and supply chains — particularly in strategic industries — back to the US,” said Choi. “For South Korea, that could mean a new battle to protect its hard-won edge, guarding against the loss of technology and skilled personnel as it undertakes certain projects.”

mkjung@heraldcorp.com