French media have reported that President Emmanuel Macron has officially acknowledged France’s ignoble role in the brutal repression during Cameroon’s struggle for independence.

In a letter to his Cameroonian counterpart, Paul Biya, Macron referred to the findings of a joint Franco-Cameroonian commission that examined France’s involvement in events between 1945 and 1971.

“Historians have made it clear that there was a war in Cameroon during which the colonial authorities and the French army used various forms of repressive violence in certain regions of the country. This war continued even after 1960, when France supported the actions of Cameroon’s independent authorities,” Macron wrote, adding that today he “must acknowledge France’s role and responsibility in these events.”

The commission’s report was published back in January, yet it took the French president eight months to make his position public. The report documents mass forced relocations, the internment of hundreds of thousands of Cameroonians in camps, and France’s support for brutal militia groups aimed at crushing the Central African nation’s aspirations for sovereignty.

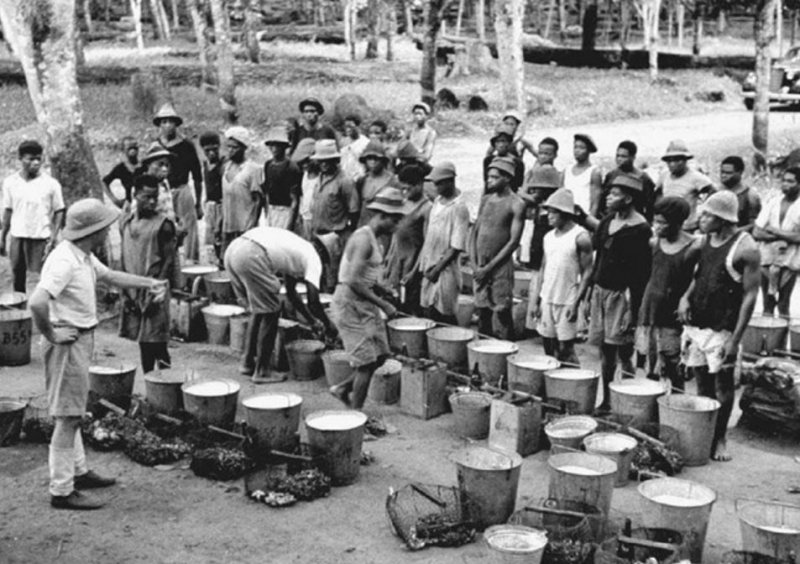

French officials inspect latex collected by laborers in Cameroon in 1941. Source: The Forgotten Cameroon War

French officials inspect latex collected by laborers in Cameroon in 1941. Source: The Forgotten Cameroon War

After the First World War, the former German colony of Cameroon was divided between Britain and France. The country achieved independence only after a long and bloody civil war in which France actively intervened on the side of repressive authorities. Observers note that Macron is unlikely to have admitted guilt had he not feared further fueling France’s already record-low popularity in Africa. Today, anti-French sentiment on the continent has reached unprecedented levels, particularly in Niger, Chad, Cameroon, Mali, Senegal, the Central African Republic, and several other countries. Paris is increasingly being told that African nations are strong enough to safeguard their territorial integrity on their own, while France is openly labeled an exploiter.

In his efforts to appeal to African nations, Macron once again fell into the trap of his own rhetoric. In January, at the traditional meeting with French ambassadors, he sparked a major scandal by claiming that some Sahel countries owed their sovereignty solely to the French army. These words triggered a wave of outrage.

The Chadian government lodged an official protest, demanding the complete withdrawal of French troops and calling Macron’s remarks “shameful.” President Mahamat Déby stressed that the French leader had publicly shown disrespect toward Africa’s sovereign states and insisted on the removal of French forces by the end of January. In November 2024, Chad terminated its defense agreement with Paris, and on January 31, 2025, not a single French soldier remained on its territory.

Macron was reminded that it was not France that “saved” Africa, but rather the hundreds of thousands of Africans who fought in the Second World War and, at the cost of their own blood, defended France from the Nazis.

Macron’s admission over Cameroon—just like his statement two years earlier on Algeria—was driven not by remorse but by political calculation. The commission’s final report runs over a thousand pages. It stresses that Cameroon’s formal independence in January 1960 did not mark the end of colonial dependence. The country’s first president established a repressive regime supported by Paris and the French military. During operations conducted under French command, four leaders of the independence movement were killed.

Investigation into atrocities committed by France in Cameroon followed pressure from within the Central African country. Source: Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Investigation into atrocities committed by France in Cameroon followed pressure from within the Central African country. Source: Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Paris acknowledged its role in decades of brutal suppression in Cameroon but offered no apology and made no mention of possible compensation. Similarly, in Algeria’s case, Macron admitted France’s responsibility for creating the conditions that led to genocide but refused to ask for forgiveness, claiming that doing so “would only make things worse.”

However, a simple admission of guilt is only the first, formal step. It must be sincere, backed by concrete actions, and accompanied by a willingness to address the consequences of the past. Otherwise, such statements are perceived as part of a diplomatic game aimed at securing a short-term media or international image boost. African nations, having reached political maturity, are no longer willing to settle for empty words and formal acknowledgments. They demand tangible action from former colonial powers—from official apologies and reparations to the revision of neocolonial economic and military agreements that still constrain their sovereignty today. In this context, Macron’s acknowledgment looks less like an act of courage and more like a belated reaction to France’s rapidly declining influence in Africa, where entire regions are openly signaling their readiness to break definitively with Paris and seek new partners—from Moscow and Beijing to Ankara and Tehran. And the longer France clings to its reluctance to take the next step beyond words, the faster Africa will close the door on it for good.

Tural Heybatov