LONDON: Eight months after the fall of the Bashar Assad regime, the world is watching and hoping that Syria, despite its fragility, can avoid partition along sectarian lines.

The latest crisis erupted in mid-July in the southern province of Suweida. On July 12, clashes broke out between militias aligned with Druze leader Sheikh Hikmat Al-Hijri and pro-government Bedouin fighters, according to Human Rights Watch.

Within days, the fighting had escalated, with interim government forces deploying to the area. On July 14, Israel launched airstrikes on government buildings in Damascus and Syrian troops in Suweida with the stated aim of protecting the Druze community.

Although they constitute just three to five percent of Syria’s overall population, the Druze — a religious minority — make up the majority in Suweida, with further concentrations in Israel and the Israeli-occupied Golan.

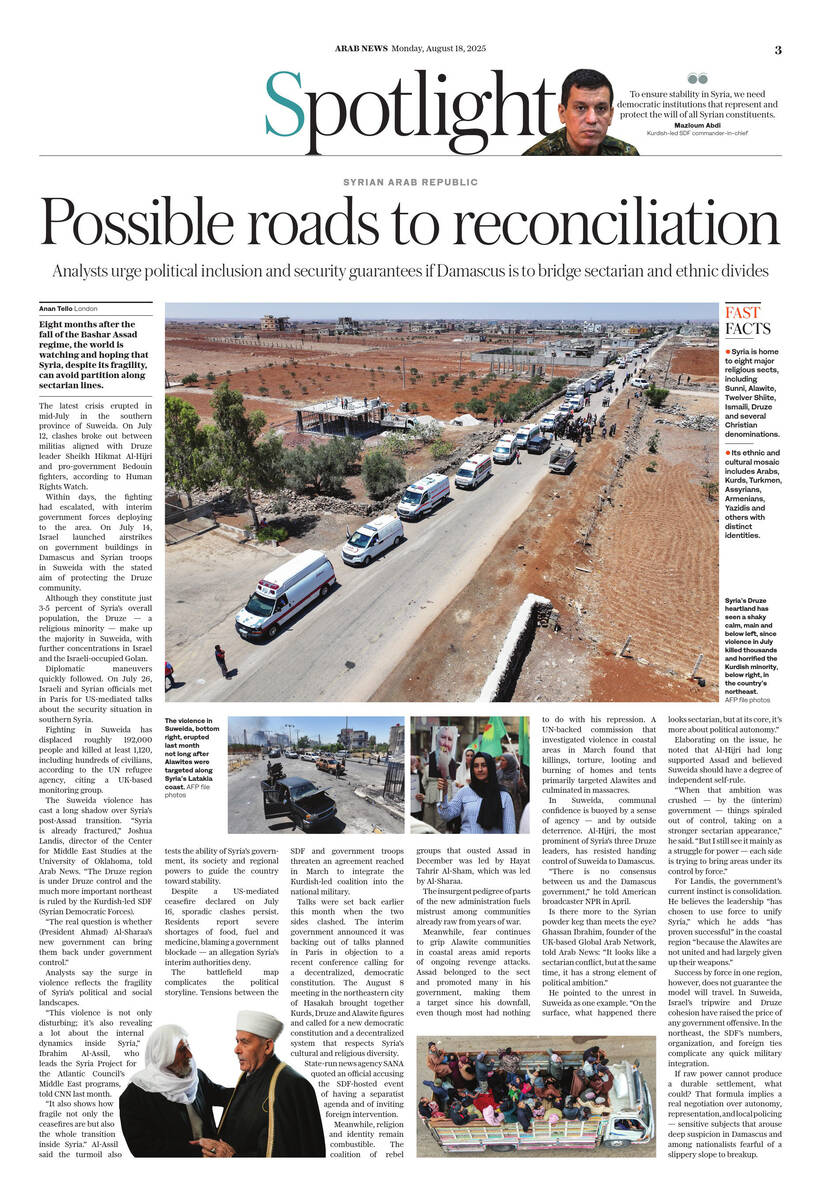

Syria’s Druze heartland in Soweida has seen a shaky calm since violence between the Druze and Bedouins in July killed thousands. (AFP)

Diplomatic maneuvers quickly followed. On July 26, Israeli and Syrian officials met in Paris for US-mediated talks about the security situation in southern Syria. Syria’s state-run Ekhbariya TV, citing a diplomatic source, said both sides agreed to continue discussions to maintain stability.

The human cost has been severe. Fighting in Suweida has displaced roughly 192,000 people and killed at least 1,120, including hundreds of civilians, according to the UN refugee agency, citing a UK-based monitoring group.

Syrian security forces deploy in Walga town amid clashes between tribal and bedouin fighters on one side, and Druze gunmen on the other, near the predominantly Druze city of Sweida in southern Syria on July 19, 2025. (AFP)

The bloodshed in Suweida has cast a long shadow over Syria’s post-Assad transition. “Syria is already fractured,” Joshua Landis, director of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma, told Arab News. “The Druze region is under Druze control and the much more important northeast is ruled by the Kurdish-led SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces).

“The real question is whether (President Ahmad) Al-Sharaa’s new government can bring them back under government control.”

FASTFACTS

• Syria is home to eight major religious sects, including Sunni, Alawite, Twelver Shiite, Ismaili, Druze and several Christian denominations.

• Its ethnic and cultural mosaic includes Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, Assyrians, Armenians, Yazidis and others with distinct identities.

Analysts say the surge in violence reflects the fragility of Syria’s political and social landscapes.

“This violence is not only disturbing; it’s also revealing a lot about the internal dynamics inside Syria,” Ibrahim Al-Assil, who leads the Syria Project for the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs, told CNN last month.

“It also shows how fragile not only the ceasefires are but also the whole transition inside Syria.”

Al-Assil said the turmoil also tests the ability of Syria’s government, its society, and regional powers — including Israel — to guide the country toward stability.

Despite a US-mediated ceasefire declared on July 16, sporadic clashes persist. Residents report severe shortages of food, fuel and medicine, blaming a government blockade — an allegation Syria’s interim authorities deny.

Camille Otrakji, a Syrian-Canadian analyst, describes Syria as “deeply fragile” and so vulnerable to shocks that further stress could lead to breakdown.

He told Arab News that although “officials and their foreign allies scramble to bolster public trust,” it remains “brittle,” eroded by “daily missteps” and by abuses factions within the security forces.

From a rights perspective, institutional credibility will hinge on behavior. Adam Coogle, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch, stresses the need for “professional, accountable security forces that represent and protect all communities without discrimination.”

Coogle said in a July 22 statement that de-escalation must go hand in hand with civilian protection, safe returns, restored services and rebuilding trust.

The battlefield map complicates the political storyline. Tensions between the SDF and government troops threaten an agreement reached in March to integrate the Kurdish-led coalition into the national military.

Mazloum Abdi, commander-in-chief of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), speaks during the pan-Kurdish “Unity and Consensus” conference in Qamishli in northeastern Syria on April 26, 2025. (AFP)

Talks were set back earlier this month when the two sides clashed, with both accusing the other of striking first. The interim government announced it was backing out of talks planned in Paris in objection to a recent conference calling for a decentralized, democratic constitution.

The August 8 meeting in the northeastern city of Hasakah brought together Kurds, Druze and Alawite figures and called for a new democratic constitution and a decentralized system that respects Syria’s cultural and religious diversity.

State-run news agency SANA quoted an official accusing the SDF-hosted event of having a separatist agenda and of inviting foreign intervention.

Meanwhile, religion and identity remain combustible. The coalition of rebel groups that ousted Assad in December was led by Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham, which was led by Al-Sharaa.

The insurgent pedigree of parts of the new administration fuels mistrust among communities already raw from years of war.

Meanwhile, fear continues to grip Alawite communities in coastal areas amid reports of ongoing revenge attacks. Assad belonged to the sect and promoted many in his government, making them a target since his downfall, even though most had nothing to do with his repression.

A UN-backed commission that investigated violence in coastal areas in March found that killings, torture, looting and burning of homes and tents primarily targeted Alawites and culminated in massacres.

Families of Syria’s Alawite minority cross the Nahr al-Kabir river, forming the border between Syria’s western coastal province and northern Lebanon in the Hekr al-Daher area on March 11, 2025, to enter Lebanon while fleeing from sectarian violence in their heartland along Syria’s Mediterranean coast. (AFP/File)

These developments across the war-weary country have heightened fears of sectarian partition, though experts say the reality is more complex.

“The risk is real, but it is more complex than a straightforward territorial split,” Haian Dukhan, a lecturer in politics and international relations at the UK’s Teesside University, told Arab News.

“While Syria’s post-2024 landscape is marked by renewed sectarian and ethnic tensions, these divisions are not neatly mapped onto clear-cut borders.”

He noted that fragmentation is emerging not as formal borders but as “pockets of influence” — Druze autonomy in Suweida, Kurdish self-administration in the northeast, and unease among some Alawite communities.

“If violence persists,” Dukhan says, “these local power structures could harden into semi-permanent zones of authority, undermining the idea of a cohesive national state without producing formal secession.”

In Suweida, communal confidence is buoyed by a sense of agency — and by outside deterrence. Al-Hijri, the most prominent of Syria’s three Druze leaders, has resisted handing control of Suweida to Damascus.

“There is no consensus between us and the Damascus government,” he told American broadcaster NPR in April. Landis, for his part, argues that Israel’s military posture has been decisive in Suweida’s recent calculus.

Taken together, these incidents underscore the paradox of Syria’s “local” conflicts: even the most provincial skirmishes are shaped by regional red lines and international leverage.

Against this backdrop, Damascus has drawn closer to Turkiye. On August 14, Reuters reported the two had signed an agreement for Ankara to train and advise Syria’s new army and supply weapons and logistics.

“Damascus needs military assistance if it is to subdue the SDF and to find a way to thwart Israel,” Landis said. “Only Turkiye seems willing to provide such assistance.”

Although Landis believes it “unlikely that Turkiye can help Damascus against Israel, it is eager to help in taking on the Kurds.”

While the SDF has around 60,000 well-armed and trained fighters, it is still reliant on foreign backers. “If the US and Europeans are unwilling to defend them, Turkiye and Al-Sharaa’s growing forces will eventually subdue them,” said Landis.

For Ankara, the endgame is unchanged. Turkiye’s strategic aim is to prevent any form of Kurdish self-rule, which it views as a security threat, said Dukhan.

“By helping the government bring the Kurdish-led SDF into the national army and reopening trade routes, Turkiye is shaping relations between communities and Syria’s place in the region.”

Could there be more to Syria’s flareups than meets the eye? Ghassan Ibrahim, founder of the UK-based Global Arab Network, thinks so. “It looks like a sectarian conflict, but at the same time, it has a strong element of political ambition,” he told Arab News.

He pointed to the unrest in Suweida as one example. “On the surface, what happened there looks sectarian, but at its core, it’s more about political autonomy.”

Elaborating on the issue, he noted that Al-Hijri had long supported Assad and believed Suweida should have a degree of independent self-rule.

“When that ambition was crushed — by the (interim) government — things spiraled out of control, taking on a stronger sectarian appearance,” he said. “But I still see it mainly as a struggle for power — each side is trying to bring areas under its control by force.”

This perspective dovetails with Dukhan’s view that “sectarian identity in Syria is fluid and often intersects with economic interests, tribal loyalties and local security concerns.”

He noted that “even in areas dominated by one community, there are competing visions about the future.” That fluidity complicates any blueprint for stabilization. Even if front lines quiet, the political map could still splinter into de facto zones where different rules and loyalties prevail.

To Landis, the government’s current instinct is consolidation. He believes the leadership “has chosen to use force to unify Syria,” which he adds “has proven successful” in the coastal region “because the Alawites are not united and had largely given up their weapons.”

Success by force in one region, however, does not guarantee the model will travel. In Suweida, Israel’s tripwire and Druze cohesion have raised the price of any government offensive. In the northeast, the SDF’s numbers, organization, and foreign ties complicate any quick military integration.

If raw power cannot produce a durable settlement, what could? For Dukhan, the transitional government’s challenge is “to prevent local self-rule from drifting into de facto partition by offering credible political inclusion and security guarantees.”

That formula implies a real negotiation over autonomy, representation, and local policing — sensitive subjects that arouse deep suspicion in Damascus and among nationalists fearful of a slippery slope to breakup.

Landis agrees that compromise is possible, but unlikely. “Al-Sharaa has the option of compromising with Syria’s minorities, who want to retain a large degree of autonomy and to be able to ensure their own safety from abuse and massacres,” he said. “It is unlikely that he will concede such powers.”

Still, experts say Syria can avoid permanent fracture if all sides — domestic and foreign — work toward reconciliation.

As Syria’s conflict involves multiple domestic factions and foreign powers, Ibrahim said international actors could foster peace by pressuring their allies on the ground. Responsibility, he stressed, lies with all sides.

“The way forward is cooperation from all,” he said. “For example, Israel could pressure Sheikh Al-Hijri and make it clear that it’s not here to create a ‘Hijristan’.”

Ibrahim was referring to the Druze leader’s purported ambition to carve out a sovereign state in Suweida.

Otrakji said that “after 14 years of conflict, Syria is now wide open — a hub not just for diplomats and business envoys, but also for military, intelligence and public relations operatives.”

The previous regime was rigid and combative, he said, but the new leadership “seems intent on pleasing everyone.”

That balancing act carries dangers — overpromising at home, underdelivering on reforms, and alienating multiple constituencies at once.

Otrakji stressed that without full implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 2254, Syria will remain trapped “on a dizzying political rollercoaster” and in uncertainty.

The UNSC reaffirmed on August 10 its call for an inclusive, Syrian-led political process to safeguard rights and enable Syrians to determine their future.

Global Arab Network’s Ibrahim concluded that Syria does not need regime change, but rather reconciliation, education and a leadership capable of dispelling the idea that this is a sectarian war.

Sectarian and religious leaders, he said, “must understand that Syria will remain one unified, central state with some flexibility — but nothing beyond that.”