When Elon Musk disagrees with someone, he calls them an “NPC” (non-player character). In video-games, an NPC is a machine-puppeted sprite that engages in predictable movements (think of the ghosts in Pac-Man) and perhaps utters some scripted (or AI-generated) dialog:

https://futurism.com/elon-musk-interviewer-npc

Seeing people as automata is probably a side-effect of sitting in the command-center of a big online service, in which you primarily interact with users as statistical aggregates in an analytics dashboard. When you nudge the “buy” button a few pixels over and see how sales rise or fall, you’re interacting with people as a mass. The dashboard tells you how “sales” respond to a change in the UI, but not how people are affected by that change.

The dashboard can’t tell you whether the change meant that some people couldn’t locate a buy-button and thus didn’t get something they needed, nor can it tell you whether some people bought something they later regretted.

Analytics allow you to relate to people the way a Simcity player does, by making a zoning change and observing the population-scale outcomes: put a road through a residential block and watch the traffic numbers improve while the happiness of the sims in that block declines.

But there’s another way in which people like Musk are inclined to view others as NPCs: the only way to become a billionaire is to hurt and exploit lots of people. You have to be willing to cheat your investors by lying about “full-self driving,” you have to be willing to maim your workers, you have to be willing to rain space debris down on people near your launchpad. If you think of those people as truly real — as being just as capable as you are of experiencing stress, sorrow, fear and anxiety — you couldn’t possibly set these crimes in motion. You have to view these people as NPCs, devoid of the rich interiority that you marinate in.

William Gibson described this mindset beautifully in Idoru, in a scene where a TV executive describes his audience:

Personally I like to imagine something the size of a baby hippo, the color of a week-old boiled potato, that lives by itself, in the dark, in a double-wide on the outskirts of Topeka. It’s covered with eyes and it sweats constantly. The sweat runs into those eyes and makes them sting. It has no mouth, no genitals, and can only express its mute extremes of murderous rage and infantile desire by changing the channels on a universal remote. Or by voting in presidential elections.

(Not for nothing, Musk frequently pumps millions of dollars into elections in the hopes of influencing all those NPCs into voting for his favored candidates, irrespective of whether those candidates will make those voters better off:)

On Twitter, Musk banned an account that reported on the movements of his private jet (that is, an account that republished public information), because he said that it made him feel unsafe. Musk also changed how Twitter’s block button worked to make it easier for gang-stalkers, griefers, harassers, and trolls to attack their victims, who are disproportionately marginalized: women, queers, people of color:

https://www.msnbc.com/opinion/msnbc-opinion/elon-musk-block-x-blue-sky-rcna176130

Musk’s fears are vivid and real to him, but the fears of millions of Twitter users are just scripted NPC behaviors. In some important sense, those people don’t actually exist for Musk. Or, as Musk put it on Rogan:

The fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy.

Not for nothing: this is also how being in a K-hole feels. Under ketamine sedation, it’s easy to feel like the whole world, your whole life to that moment, was a dream or a hallucination. The whole universe is just a figment of your imagination, and you are its god and creator. In a K-hole, other people aren’t real.

Now, as it happens, there’s a long moral tradition that condemns people who treat others as unreal, as means to an end, rather than as ends unto themselves. For Kant, this is so odious that he said it violated the “categorical imperative”:

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/persons-means/

Or, as Terry Pratchett’s Granny Weatherwax put it:

Sin is when you treat people like things. Including yourself. That’s what sin is.

https://brer-powerofbabel.blogspot.com/2009/02/granny-weatherwax-on-sin-favorite.html

But when you are seeing like a billionaire, that’s how people appear to you: as things. It’s the mindset that leads to you offering your subordinate a thoroughbred horse in exchange for fucking you:

Seeing like a billionaire is when you view people as aggregated masses without any real interiority or will. Hence “high agency,” the term that people who aspire to extreme wealth and power use to describe themselves. If the elite are high agency, then it follows that the masses are low agency. They have few desires or real feelings:

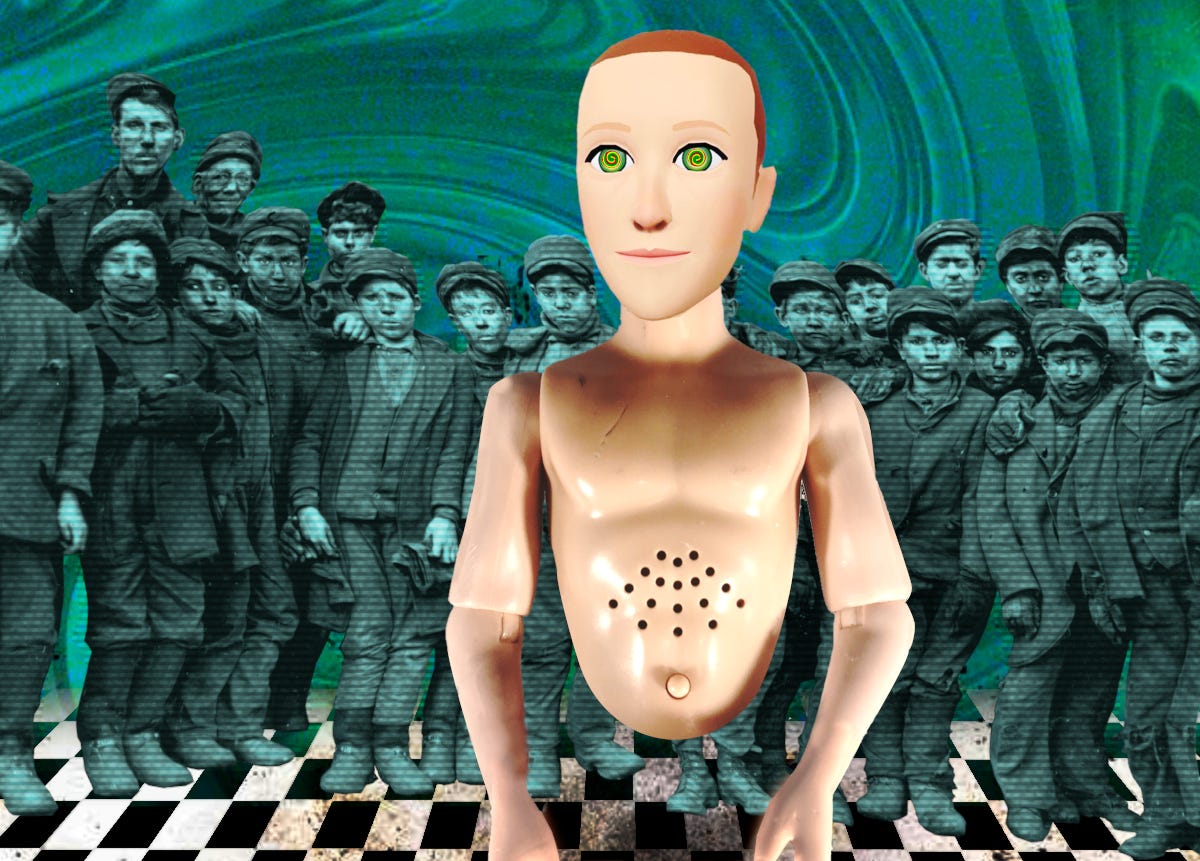

It’s not just Musk who views people this way. Mark Zuckerberg has been treating people as things for his entire life, ever since he started Facebook in his dorm-room so that he could nonconsensually rate the fuckability of his fellow Harvard undergrads. In Careless People, Sarah Wynn-Williams’ whistleblower memoir of her time as a top FB exec, we get a picture of Zuck as someone who just doesn’t think that other people are real enough to matter:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/04/23/zuckerstreisand/#zdgaf

It’s no wonder that Zuck thinks that chatbots can replace our friends:

https://fortune.com/2025/06/26/mark-zuckerberg-ai-friends-hinge-ceo/

At some foundational level, he thinks we are all chatbots, automata driven by manipulable inputs that drive deterministic outcomes. This is a guy who claims to have invented a mind-control ray using warmed-over Skinnerian behavior mod techniques:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/05/07/rah-rah-rasputin/#credulous-dolts

Sam Altman, another person who sees like a billionaire, and wants to replace our friends with chatbots, claims that humanity is nothing more than a “stochastic parrot” — a statistical autocompleting program that does not truly understand or think:

https://x.com/sama/status/1599471830255177728?lang=en

Billionaires have to be solopsists, or at least, selective solopsists, who don’t really believe in the humanity of the people who create their wealth and whom they wield their power over. This has always been clear, but the idea that we can replace our social connections with chatbots erases any doubt.

Billionaires just don’t think we’re real.