Archaeologists in Norway have uncovered a rare 3,000-year-old carved stone at a prehistoric cult site buried beneath clay after a massive landslide.

The discovery, made in Gauldal Valley in Central Norway, sheds light on Bronze Age ritual practices and offers new insight into how ancient communities connected with death, religion, and nature.

A Landslide That Preserved History

Around 800 BCE, a catastrophic landslide struck Gauldal, covering the river valley with thick layers of clay. For centuries, the ancient site remained hidden until archaeologists began excavations in 2014 during the expansion of the E6 highway.

“The whole area is covered in clay from that landslide,” explained archaeologist Hanne Bryn of the NTNU University Museum, who has led the research since the first survey. “We quickly saw signs of human activity, but what we eventually uncovered was far beyond our expectations.”

The excavation required two full summers instead of one, as the team had to dig through clay layers up to three meters thick. What they found underneath was extraordinary.

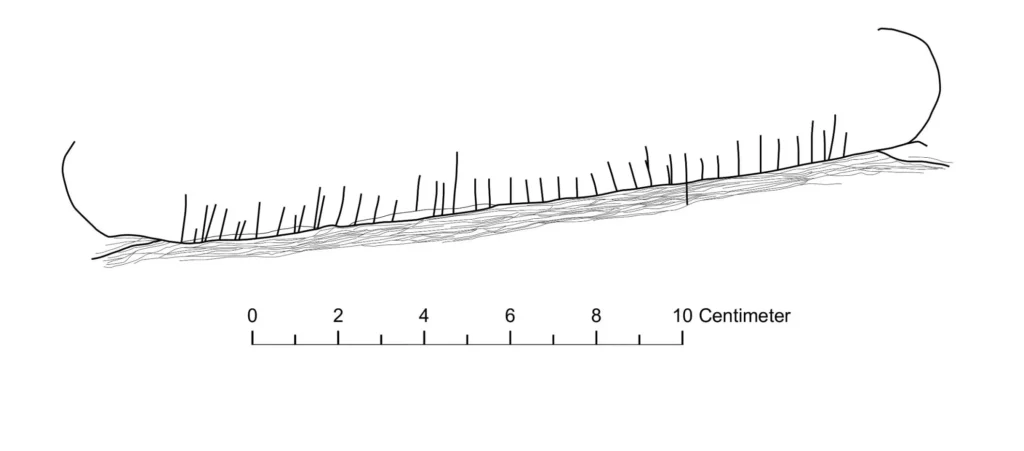

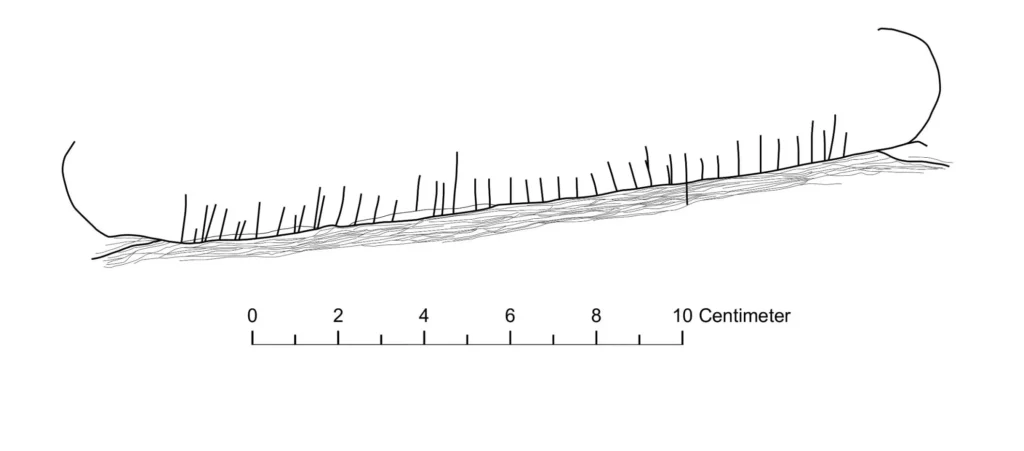

The 3,000-year-old carved stone, measuring 10 × 20 cm, with human, animal, and boat engravings on both sides. Credit: Hanne Bryn / NTNU University MuseumA Unique Cult Site in Central Norway

The 3,000-year-old carved stone, measuring 10 × 20 cm, with human, animal, and boat engravings on both sides. Credit: Hanne Bryn / NTNU University MuseumA Unique Cult Site in Central Norway

Archaeologists identified the site as a 3,000-year-old Bronze Age cult center. Unlike ordinary settlements, it consisted of two main zones, each with a longhouse about 10 to 12 meters in length and associated burial structures.

One area featured a large burial cairn—a mound of stones marking a grave—along with three stone slab chambers. These chambers held cremated human bones dated between 1000 and 800 BCE, coinciding with the time of the landslide.

Scattered across the site were several decorated stones, including one with a carved footprint complete with toes and cup marks—small circular depressions common in prehistoric rock art. Near one longhouse, archaeologists found a semicircle of stones with similar markings, suggesting ritual significance.

The Rare Portable Carved Stone

The most remarkable discovery was a small portable stone, about 20 by 10 centimeters, hidden beneath a cluster of larger rocks. Unlike most rock art in Norway, which is carved directly into bedrock, this stone was designed to be carried.

On one side, it features a human figure alongside what appears to be a dog. Above the figure’s hand, a bow and arrow are engraved using a different technique. On the other side, another human figure is depicted next to a ship and an unidentified symbol.

“It’s so small you could carry it in your pocket,” said Bryn. “Finding a portable engraved stone like this in its original ritual context is extremely rare. We have nothing else quite like it in Central Norway.”

The carved stone shortly after its discovery. Credit: Hanne Bryn / NTNU University MuseumRitual Practices and Symbolism

The carved stone shortly after its discovery. Credit: Hanne Bryn / NTNU University MuseumRitual Practices and Symbolism

The layout of the site suggests it was not a residential area but rather a gathering place for ceremonies, rituals, and burial practices. Cooking pits and traces of bronze casting were also discovered, hinting at communal feasts or offerings.

“The combination of burial mounds, carved stones, and the portable engraving strongly points to ritual use,” Bryn explained. “This was a site of spiritual importance where people connected with their ancestors and the natural world.”

Was the Site in Use When Disaster Struck?

One of the lingering mysteries is whether the site was still active at the time of the landslide. The cremated remains date to the same period, but no direct evidence of people being caught in the disaster has been found.

“It wasn’t a Pompeii,” Bryn noted, referencing the Roman city buried in volcanic ash. “There are no signs of sudden abandonment, but it’s possible the community was still using the site when the clay slide covered it.”

Drawing of the carved boat on the small stone. Image Credit: Kristoffer R. Rantala / NTNU University Museum

Drawing of the carved boat on the small stone. Image Credit: Kristoffer R. Rantala / NTNU University MuseumA Rich Bronze Age Landscape

Gauldal and the surrounding region are known for Bronze Age rock carvings, particularly depictions of ships and hunting scenes. Similar engravings have been found near Gaulfossen and on nearby plateaus, suggesting the valley was an active ritual landscape thousands of years ago.

“This whole area was culturally significant during the Bronze Age,” Bryn said. “The concentration of carvings and burial sites shows that it was a gathering place for religious activity.”

Future Excavations

Excavations are ongoing, as Bryn and her team continue to investigate a plateau just above the original site. With every new find, archaeologists hope to piece together more of the puzzle about how ancient Norwegians lived, worshipped, and remembered their dead.

For now, the portable carved stone stands out as a singular discovery—an object that survived disaster and time, carrying with it the echoes of ritual, belief, and human creativity from 3,000 years ago.

Cover Image Credit: Drone view of the 2017 excavation in Gauldal Valley. Kristin Eriksen / NTNU University Museum