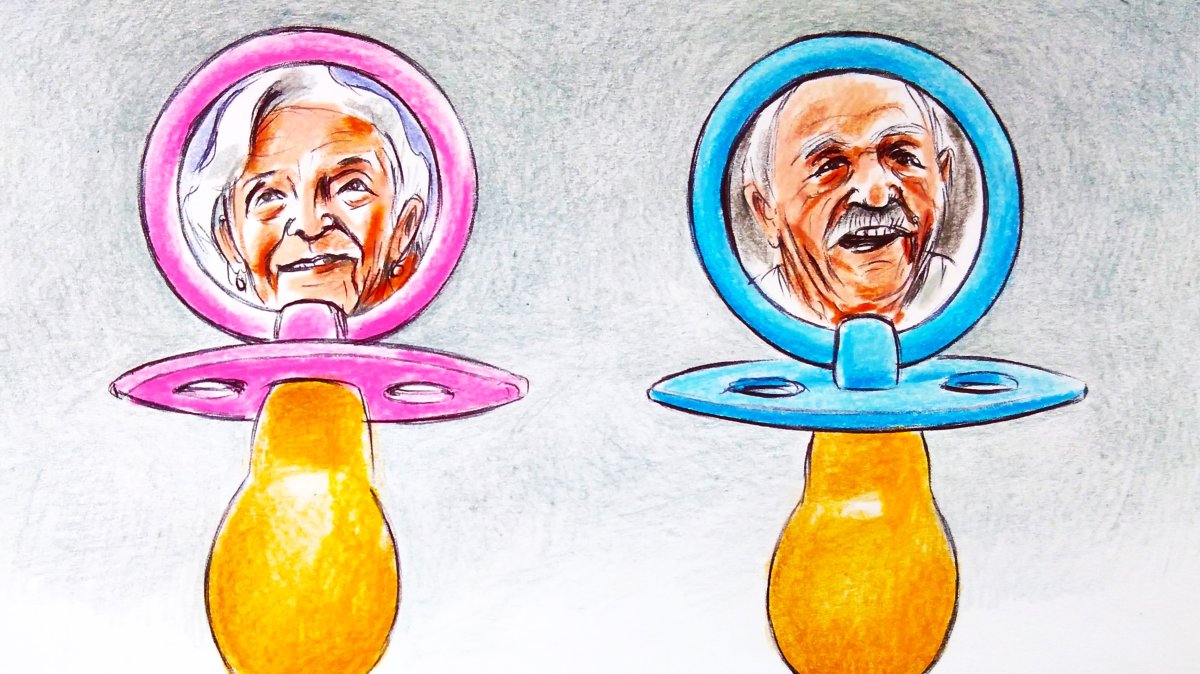

Demographic change is the gradual but profound transformation in the size, structure, and distribution of a population over time, and one of its most powerful drivers is aging. As fertility rates decline and life expectancy rises, the proportion of older individuals grows while the share of younger age groups shrinks. This process, known as population aging, reshapes societies in fundamental ways: shrinking workforces, exploding dependency ratios, shifting social structures, unsustainable welfare regimes, and altering demands on health care, pensions, and housing.

Far from being a local phenomenon, aging is a global trend affecting both wealthy nations and emerging economies, challenging policymakers to rethink how to sustain economic vitality and social cohesion. These are strange times, for the first time in history, the elderly will soon outnumber children. All developing countries are now navigating this same demographic crossroads, moving rapidly from youthful populations to aging societies in just a few decades, a transition that took richer nations more than a century to complete.

As an emerging economy, Türkiye is passing through the same trajectory. The country is racing toward an age milestone that could redefine its economy, politics and social fabric, and it’s happening faster than most realize. Fresh figures from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) reveal a sharp drop in the child population, a record rise in the share of elderly citizens, and a median age climbing year after year alarmingly. The country is on the brink of a demographic shift that, if left unchecked, could strain pensions, slow growth, and challenge the very foundations of its social model.

Recent figures of Turkish demography

Türkiye is quietly crossing a historic threshold, one that will shape its economy, politics and social fabric for decades. Recent figures from TurkStat confirm what demographers have been warning: The country is aging at a speed that should alarm policymakers.

When looked at the recent figures, in 2024, the share of children (0–14) in the population fell to just 30.6% in dependency terms, down from 32.3% in 2022, while the elderly dependency ratio (65-plus) rose to 15.5%, its highest ever. As another striking data, each year the median age is breaking records of the history of the republic, one after another, as the median age climbed to 34.4 years overall in 2024, with women already averaging 35.2. This shows the fact that Türkiye is not classified as a young population country anymore.

The trend lines are unmistakable: Projections show that by 2050, under the main scenario, nearly one in four Turks will be over 65. In the low fertility scenario, that figure is even starker, one in four by mid-century, and one in three by 2100.

Recent official demography data clearly demonstrates that Türkiye is undergoing a radical transformation in its demographic structure. The significant decline in marriage rates, steady increase in divorce rates, young people increasingly moving up the age of marriage and choosing to have fewer children, increase of single-person households, and the shift in social expectations of Generation Z have triggered a radical change. Türkiye’s fertility rate fell to 1.51 by 2023, far below the 2.1% fertility rate considered the gold standard for population renewal. This trend not only accelerates the aging of the population but also has the potential to have profound long-term impacts on numerous areas, from labour supply to the social security system.

Crisis has already arrived

The problem is not in the future; it has already arrived. The recent data exposes that the window of opportunity is shrinking fast for Türkiye. The 65-plus share rose to 11.0% as of July 1, 2025, from 10.4% on July 1, 2024. This exposes that the elderly Turkish population (65-plus) has almost reached 9,5 million, by half a million increase within a year.

The raw numbers underscore the urgency. In 2024, there were 3.33 million people aged 65-69, but only 5.22 million under the age of 5. Compare that to two decades ago, when young children vastly outnumbered new retirees. The pipeline of the working-age population is shrinking; TurkStat’s projections show the 15-64 age group’s (which is defined as the working-age population) share falling from 68.9% today to barely 55% by the late 21st century. That is the silent demographic squeeze that will pressure pensions, health systems and economic growth.

Turkish figures are not just a statistical curiosity. The combination of declining fertility, rising life expectancy at birth (now 75.5 years overall in the 2022-2024 period), and rapid urbanization is transforming the structure of Turkish households. Average household size dropped to 3.11 persons in 2024, with single-person households rising to 20%, up from 19.4% just two years earlier. In a society long anchored in extended family networks, the implications for elder care, social isolation and housing demand are profound.

And yet, unlike Japan or parts of Western Europe, which had decades to adjust, Türkiye is facing this demographic inversion at middle-income levels, with weaker safety nets. The old-age dependency curve is rising before the country has grown rich enough to afford the cost.

The contrast is sharp: After a historical low record of 1.1 per thousand in 2023, in 2024, annual population growth was just 3.4 per thousand, a far cry from the baby boom decades. Migration softens the slowdown, but not enough to reverse it, and foreign arrivals have actually declined in recent years. Without a policy course correction, the country will soon face the classic “getting old before getting rich” trap.

Urgent policy intervention required

The warning signs are not subtle. If Ankara continues to focus solely on short-term political cycles, it risks sleepwalking into a structural crisis: labor shortages, surging health care expenditure, and pension deficits that could destabilize public finances. The policy menu is well-known, including incentives for family formation, better work-life balance for women, reform of retirement systems, targeted migration strategies, and investments in automation and productivity.

What is missing is not the diagnosis, but time. Urgent policy interventions are required if the country wants to protect its generous welfare regime established in the last two decades.

The government has increasingly recognized the challenges posed by an aging population and has periodically introduced strategies aimed at extending working lives, promoting private pension schemes, and encouraging family support mechanisms. Recent plans have included largely family-oriented policies of the Ministry of Family and Social Services. However, these measures remain largely incremental and mirror approaches pursued over the past two decades, offering little innovation. Consequently, they are unlikely to effectively address the structural demographic pressures Türkiye faces, as repeating the same policies while expecting different outcomes is inherently inadequate.

The country is facing potentially devastating socio-economic problems. The demographic change is mounting pressure on the social security system, health care infrastructure and long-term care services, while also constraining economic growth potential. Moreover, changing the structure of the economy from labor-intensive to capital-intensive and from low value-added production towards high-tech is an urgent necessity for the country.

Given the accelerating pace of population aging, there is an urgent need to establish a premium-based long-term care insurance system in Türkiye. Such a mechanism would distribute the financial responsibility for elder care more sustainably by pooling contributions over individuals’ working lives, rather than relying solely on strained public budgets or informal family support. Without this reform, the rising demand for professional caregiving, nursing homes, and home-based medical services will quickly outstrip existing capacities, leading to inequities in access and quality. A well-designed premium-based model could not only ensure predictable funding but also incentivize early enrolment, preventive health measures and the growth of a formal care economy capable of meeting future needs.

Last but not least, the country urgently needs to implement a qualified immigration program, one that attracts younger, skilled workers who can bolster the shrinking labor force and help sustain the principle of intergenerational solidarity for Türkiye’s nearly 17 million retirees. Without such a measure, the demographic imbalance will deepen, placing unprecedented pressure on labor markets, pension systems, health care and the broader economy.

Nonetheless, without comprehensive reforms to be started as soon as possible that integrate labor market activation, targeted immigration policies, and sustainable pension restructuring, the demographic transition risks eroding intergenerational solidarity and creating a heavier fiscal burden on future generations.

Yes, Türkiye is facing an aging crisis. This is a fact well known. Yet, this is not a distant future problem. It is here, it is accelerating, and it will reshape the country’s possibilities long before today’s children reach middle age. If there is ever a moment for urgency, long-term thinking in Ankara, it is now. The demographic clock is ticking loudly.