The New Zealand Government’s Draft Long-term Insights Briefing (LTIB) is a timely and well-argued call to shift hazard management from reactive to proactive. It usefully covers such hazards as earthquakes, tsunami, local volcanic activity, severe weather, and space weather like solar storms.

However, the LTIB neglects important global catastrophic risks that could completely overwhelm domestic response capacity. One such risk arises from artificial intelligence which could cause a range of catastrophes, including from bioengineered pandemics. It also omits global sun-blocking catastrophes that could arise from nuclear winter scenarios or large volcanic eruptions such as the “year without a summer” from the Tambora eruption in 1815. These sun-blocking catastrophes could threaten population food security, especially when combined with major trade disruptions, for example a lack of imported liquid fuel after nuclear war.

Fortunately, there are a range of preventive measures and resiliency building measures that the Government can still explore.

The new Briefing (LTIB) on hazards – some good progress

The Government of Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) is to be congratulated on having Long-term Insights Briefings (see also our previous commentary here:1). This new Draft LTIB2 clearly articulates important major hazards such as earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, space weather, and severe-weather losses.

The LTIB makes an appropriate diagnosis of reactive tendencies (overreliance on bail-outs/insurance and ad-hoc recovery), and a need to pivot to proactive, cost-effective risk reduction. It includes consideration of nature-based solutions, appreciation for mātauranga Māori, and a particularly good discussion around trade-offs.

This LTIB also identifies technology and information-system dependencies, including concentrated semiconductor supply chains. It recognises that modern hazards co-occur and cascade, and potentially interact with national-security threats and cyber risks. Furthermore, it provides an up-to-date catalogue of NZ Government efforts to systematise risk management and adaptation.

Four key omissions and why they matter

Despite its solid foundations, this LTIB lacks wider context (eg, the global polycrisis3), and has important specific gaps. Below we detail only four major ones and note that space does not permit us detailing multiple additional areas for potential improvement.

1) AI-related catastrophic risks

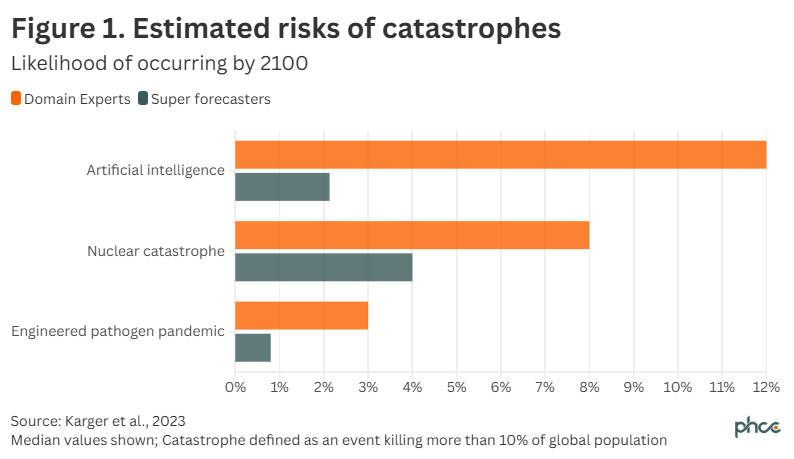

The LTIB appropriately recognises some potential benefits of AI for risk management, but fails to adequately address the dark side of this emerging technology: AI-related catastrophes. AI-related hazards include robot armies, cyber-attacks and manipulation of nuclear weapon control systems.4 Such catastrophes are estimated to be more likely than other major types by some expert groups5 (see Figure), and over 350 AI experts supported a call for immediate action.6 The risks could plausibly even involve eventual AI-takeover of human societies using such means as the generation of multiple simultaneous bioengineered pandemics.7

The NZ Government needs to work with other like-minded countries to promote international treaties around AI governance and reduce associated bio-risks. But it also needs to build specific resiliency around protecting against cyber-attacks and AI-generated misinformation (a top risk in a recent UN Report8).

2) Nuclear war and nuclear winter

A recent US National Academy of Sciences Report details the risk of nuclear winter and societal collapse following various nuclear war scenarios.9 Despite this, and other expert concerns around the risk of nuclear war,5 10 11 the LTIB does not mention this topic (nor does NZ’s publicly-facing National Risk Register12). Some NZ-specific work on nuclear war impacts and potential responses has been done recently,13 14 15 1617, the UN is progressing new research on nuclear war impacts, and older work is still of some relevance.18 19 20

As with AI-risks, the NZ Government needs to work with other like-minded countries to reactivate nuclear disarmament initiatives and get nuclear weapons off high-alert status. But in case prevention fails, it also needs to build resiliency for catastrophes on the scale of nuclear war, drawing on previous NZ work.

3) Other sun-blocking catastrophes (volcanic winters)

The LTIB emphasises local volcanic hazards (Taranaki, the Auckland Volcanic Field), yet bypasses volcanic events that could cause supply chain collapse21 or events that could involve a volcanic winter. The risk of the latter is non-trivial22; we know that the Tambora eruption in 1815 produced “the year without a summer”, widespread crop failures, and famines in multiple countries.23 24 There is even some evidence that this eruption led to climate cooling in NZ.25 Fortunately, many of the resiliency building measures that NZ could undertake, overlap with those for nuclear winter scenarios (see above).

4) More extreme pandemics

The LTIB treats pandemics as a major hazard but does not adequately detail the changing threat landscape. Advances in both AI and biotechnology have increased the risk of extremely severe bioengineered pandemics and the risk of natural pandemics continues to grow.26 27 The NZ Government needs to work internationally to improve AI governance (see above), to strengthen existing international pandemic treaties, and promote an upgrade of the Bioweapons Convention. A pandemic treaty with Australia28 could also help. The Government should also consider enhancing regional infectious disease surveillance and improving national surveillance (for example, through early-warning systems based on metagenomic testing of sewage29).

If prevention of a bioengineered pandemic fails, then the country needs the capacity to rapidly close its borders. Such an approach is backed by the relative success of border control for island nations for the Covid pandemic.30 If any pandemic spread occurred before border closure, then elimination efforts may be required. One measure that could help ensure successful elimination via stay-at-home orders is having personal protective equipment (PPE) for all really essential workers (eg, those supplying food and operating the electrical grid etc31).

Concluding assessment

This LTIB covers some important hazards and its core message of moving from reaction to prevention and resilience investment is a key one. But a comprehensive LTIB must squarely confront global catastrophic risks and then link to the preventive measures and resiliency measures needed to more comprehensively protect the country.

Individuals and organisations wanting to comment on national resiliency to catastrophes and more local disasters, should consider submitting on this LTIB (deadline 27 August).

Authors details

Prof Nick Wilson, Co-Director, Public Health Communication Centre, and Department of Public Health, Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka, Pōneke | University of Otago, Wellington

Dr John Kerr, Public Health Communication Centre and, Department of Public Health, tākou Whakaihu Waka, Pōneke | University of Otago, Wellington

Dr Matt Boyd, Director, Adapt Research Ltd