While the green and digital transitions will inevitably lead to job losses, the real danger lies elsewhere. A lack of investment in green technologies risks seeing new low-carbon industrial jobs created outside Europe, leaving the continent behind in the race for clean-tech dominance.

Decarbonising the economy and bringing human activity back within planetary boundaries is having—and will continue to have—profound impacts on employment and skills. The policies necessary to correct our current resource-depleting production and consumption model affect the world of work both qualitatively and quantitatively. Whilst the transition to a net-zero carbon economy will create millions of jobs, many will also disappear or relocate to other regions. This will alter the aggregate composition of employment, including unionisation rates and collective bargaining coverage.

This unprecedented wave of restructuring intersects with technological change—digitalisation, automation and the growing role of artificial intelligence—and unfolds in a newly conflictual geopolitical context. The effects will be unequal across multiple dimensions: skills, gender, age, economic activity and region. History shows that changes and shocks tend to generate further inequalities. This is particularly true of the dominant green transition model, which relies on the concept of green growth, is technology-driven and assigns a key role to market forces. Without addressing the inequalities likely to emerge from the decarbonisation imperative, we cannot avert the existential threat of climate change—social conflict will block or slow necessary changes.

The transition to a zero-carbon economy is fundamentally redefining comparative advantages. Leadership in combustion engines offers no template for the era of electromobility. Similarly, expertise in carbon-intensive steel production provides little employment security in the age of green steel. Whilst concerns often focus on potential job losses from industrial decarbonisation, the more pressing issue is how lagging decarbonisation efforts may threaten jobs in a world where competitiveness in clean technologies becomes increasingly decisive.

The discourse has centred on fears of “carbon leakage”—the notion that higher environmental and climate standards might drive carbon-intensive activities abroad. However, the real risk is that insufficient investment in green technologies will result in new low-carbon industrial jobs being created elsewhere, beyond Europe’s borders. This is why we cannot discuss the employment dynamics of the green transformation in isolation from simultaneous economic, technological and geopolitical trends.

The Contested Concept of “Green Jobs”

The term “green jobs” has entered mainstream discourse, embraced by trade unions, environmental NGOs, the International Labour Organization (ILO) and policymakers alike. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP 2018), green jobs are defined as “positions in agriculture, manufacturing, R&D, administrative, and service activities aimed at substantially preserving or restoring environmental quality”. “Green” has become shorthand for processes, products and services relating to sustainability and the environment.

Yet aligning this terminology with established statistical classifications remains challenging, despite various attempts. Studies and statistical approaches have tried, with varying success, to identify products and services meeting criteria for a green economy. A European Commission expert document focuses on “greening occupations” and identifies structural labour market changes linked to four key processes:

Job creation: new jobs emerge to reduce environmental pressures or increase resource efficiency (such as positions in renewable energy generation)

Job substitution: shifts in economic activity within or across sectors, from resource-intensive to more circular activities (the automotive sector exemplifies this, as combustion engine jobs disappear whilst positions in software development and battery manufacturing emerge)

Job destruction: job losses with no direct replacement, typically in sectors with significant adverse environmental effects (such as fossil fuel-based energy generation)

Job redefinition: existing jobs changing their skill sets and profiles as part of the transition to a more sustainable economy (the construction industry provides a clear example, as building retrofitting and low-carbon construction technologies require new skills and work processes)

The OECD 2024 Employment Outlook distinguishes between “green-driven occupations” and “greenhouse gas-intensive occupations”. The former category includes:

Occupations emerging from the green transition that didn’t previously exist (such as carbon trading analysts or wind turbine service technicians)

Green-enhanced skills occupations—existing roles whose skills and tasks are changing due to the green transition (such as plumbers now specialising in heat pump installation)

Green-increased demand occupations providing goods and services required by green activities (such as construction workers or chemists)

The report emphasises that whilst greenhouse gas-intensive occupations (comprising seven per cent of total employment) face the most expected job losses, they share similar skill requirements with other jobs, including green-driven occupations. This suggests transitions are possible with targeted retraining. However, the report notes that moving towards emerging green-driven occupations proves more challenging for workers in low-skilled positions than for the highly skilled, demanding urgent policy action to ensure no one is left behind.

Regarding job distribution estimates, the report finds that more than a quarter of jobs across the OECD face strong impacts from the net-zero transition. Twenty per cent of the workforce is employed in green-driven occupations, of which:

46 per cent are existing occupations whose skill sets are being altered by the green transition (“green-enhanced skills occupations”)

40 per cent are existing jobs that will be in demand because they provide goods and services required by green activities (“green increased demand occupations”)

Only 14 per cent can properly be described as “green new or emerging occupations”

Forecasts on Green Job Creation

Most European Commission communications announcing climate policy initiatives begin with forecasts portraying the green transformation as a win-win scenario with net positive employment effects. According to projections from 2021, delivering a 55 per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels would result in a net increase of up to 884,000 jobs—a 0.45 per cent rise by 2030 compared to business as usual.

A further study by Ernst and Young (2021), analysing investment projects under the EU Next Generation Recovery Fund devoted to the green economy, found that these projects represent €200 billion in aggregate investment and could create 2.3 million jobs.

Cedefop (2021) estimated that implementing the European Green Deal would create an additional 2.5 million jobs—more than one per cent growth—by 2030, not only in sectors driving the green transition but also in administrative and support services, legal, accounting and consulting services, and computer programming and information services.

With the announcement of the Green Deal Industrial Plan (European Commission 2023), the Commission’s factsheet stated: “The green transition could create up to 1 million additional jobs in the EU by 2030. For example: by 2030, solar energy employment could reach 1 million jobs. In the battery sector approximately 800,000 workers will need to be trained, upskilled, or reskilled by 2025 to meet the demand of this sector for new workers.”

The main shortcoming of such forecasts is their target-based nature, assuming that policy objectives (such as 2030 climate targets) will be met through EU manufacturing capacity. These projections fail to account for industrial, trade and investment policy repercussions and view developments in isolation from global dynamics.

Fragmented Evidence on the Green Jobs Landscape

Even with most studies projecting a moderate but clear net positive employment effect at aggregate economic level, regional and sectoral differences can be enormous. Three main sector categories emerge: those facing significant operational reduction (such as fossil energy), those requiring profound transformation (such as the automotive sector), and those with the greatest job creation potential (circular economy sectors).

Evidence shows that whilst jobs have indeed been created, the rate of creation remains muted and uneven. More troublingly, jobs in key clean technology sectors actually fell between 2018 and 2022.

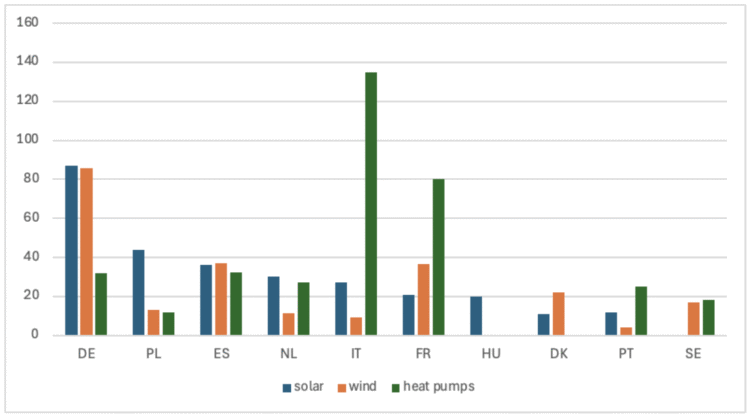

Data compiled by the Bruegel think tank (2024) provides a more detailed, though still fragmented, picture. As of 2022 (the latest available data), the EU-27 had 347,000 jobs in solar energy, 273,500 in wind and 416,200 in heat pumps—just over one million in total. These jobs concentrate in ten member states shown in Figure 1 (averaging around 80 per cent of the EU total). Germany leads in solar and wind power jobs (87,000 and 86,000 respectively), whilst Italy dominates heat pump employment (135,000), followed by France (80,000).

Figure 1. Number of workers in the solar, wind energy and heat pump sectors (2022, thousand persons (FTE))

Source: Jugé et al. (2024).

Whilst Figure 1 offers only a 2022 snapshot, it’s crucial to note that Germany, Italy and Denmark all experienced job losses in these sectors between 2017 and 2022. Based on the Bruegel database (not shown in Figure 1), manufacturing employment in Germany’s wind energy sector plummeted from 140,800 in 2017 to 86,600 by 2022. Over the same period, Denmark saw a decline from 34,200 to 22,400, whilst Spain remained steady at around 37,000. Italy, despite leading in heat pumps with 85,000 jobs in 2022, had lost 6,000 positions by that year. Spain witnessed heat pump job losses from 68,000 in 2018 to 32,000 by 2022, and Portugal’s numbers fell from 80,000 in 2019 to 25,000 by 2022.

Whilst these losses had multiple causes, the trend highlights challenges in both investment activity determining deployment rates (the demand side for manufacturing) and European manufacturers’ market share in meeting this demand.

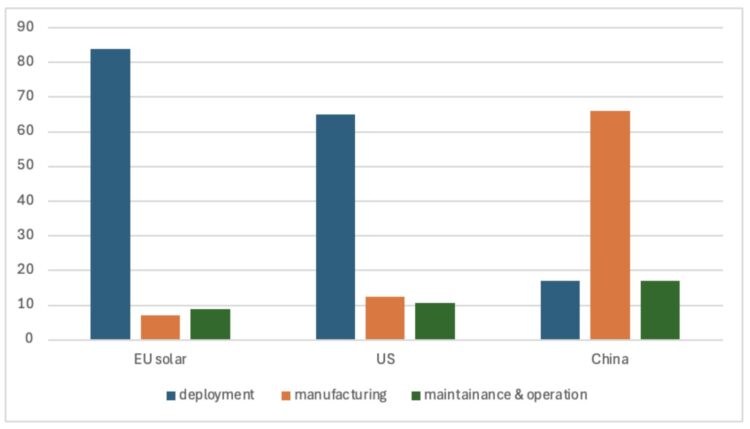

Even with limited data availability, it’s clear the last decade failed to deliver the expected boom in Europe’s key clean energy sectors. This slow and volatile job creation indicates that Europe’s transition to net-zero emissions remains suboptimal from an employment perspective. Figure 2 illustrates the challenges facing the EU clean industry sector. The contrasting job distribution within the solar sector between the EU and China reveals a stark reality: whilst two-thirds of China’s solar jobs are in manufacturing, a mere seven per cent of EU solar jobs involve manufacturing, with 84 per cent in deployment—essentially fitting imported solar panels on European roofs. Since the collapse of EU solar panel manufacturing, this has become the cautionary tale to avoid in other clean industry segments.

Figure 2. Distribution of employment by type of activity in the solar sector

Source: Jugé et al. (2024).

Conclusion

The green transformation produces three broad types of employment change. Fossil fuel-based energy generation and related activities will be phased out, and these jobs—in their current form—will disappear, though they represent a small share of European employment. Existing industries undergo deep decarbonisation whilst a new clean technology-based manufacturing landscape emerges. These two segments—energy-intensive industries and clean industry—are deeply intertwined and inseparable.

The challenge lies in the absence of coordinated, cooperative global decarbonisation. Countries and regions pursuing more ambitious paths—like the EU—face higher initial costs and suffer temporary competitiveness losses. This phenomenon, labelled carbon leakage, can be partially addressed by creating a level playing field, which the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) aims to achieve. But this isn’t enough.

Far more comprehensive industrial policies are needed to manage these industries’ technological transformation, which will generate competitive advantages in the longer term. Without such policies, affected industries resort to calling for reduced transition pace (such as regarding the 2035 phase-out of combustion engines), easing financial burdens (such as subsidies for electric energy in Germany), or relocating production within the EU to exploit energy cost differentials (such as ArcelorMittal).

The question becomes: how can Europe tap the job creation potential of the green economy? If new jobs in clean industries emerge too slowly and transformation becomes protracted and chaotic, international competitors may capture larger market shares in critical clean industry segments—ultimately costing Europe more jobs in the long term.

One lesson emerges clearly: there is no one-size-fits-all just transition policy. Europe needs targeted, integrated transformation policies combining labour market measures, social protection to cover transformation risks, secured investment, and sensible industrial and trade policies. Without this comprehensive approach, the continent risks losing not just the climate race, but the employment opportunities that should accompany the green transition.