If there was one person above all others who was responsible for Black Wednesday, the financial crisis that led to Britain’s humiliating withdrawal from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) in 1992, it was perhaps Helmut Schlesinger, then president of the German Bundesbank.

Schlesinger, the high priest of rigid monetary discipline, had sharply increased German interest rates to counter rising inflation caused by the reunification of East and West Germany. This had put severe pressure on other European governments to follow suit, regardless of the strength of their economies, because their currencies were pegged to the deutschmark.

At an acrimonious meeting of European finance ministers in Bath that September, Norman Lamont, chancellor of the exchequer in John Major’s Conservative government, spoke for many of his fellow ministers when he repeatedly pressed Schlesinger to revalue the deutschmark or cut interest rates. Time and again the German refused, and at one point threatened to walk out.

A few days later, on September 15, Schlesinger compounded matters by giving an interview to the German financial newspaper Handelsblatt. He said that despite Italy’s devaluation of the lira, “the tensions in the ERM are not over” and “further devaluations are not excluded”.

As Major wrote in his memoirs: “Such views from one of the most influential central bankers in the world sent out only one message to the markets: ‘Sell sterling.’” The Bundesbank ignored the Bank of England’s plea for a swift and strong denial of what Major described as Schlesinger’s “thoughtless” words and, as the prime minister put it, “carnage began”.

The pound plunged overnight. The Bank of England intervened on a massive scale to try to prop it up. The government announced that it was raising interest rates from 10 to 12 per cent, and then to 15 per cent, but to no avail. At 7.30pm that Wednesday evening Lamont announced from the steps of the Treasury that Britain was suspending its membership of the ERM. The Conservatives’ reputation for economic competence was destroyed.

Major was furious with Schlesinger, who had been “unavailable” when Robin Leigh-Pemberton, then Bank of England governor, had tried to contact him earlier on Black Wednesday. “Neither Norman nor I hid our dismay at how the Bundesbank had behaved,” he wrote.

Schlesinger left the Bundesbank the following year as a hugely respected figure in the world of international finance. During his 41 years at that institution he had transformed the deutschmark into one of the world’s most stable currencies and made it the anchor currency of the ERM — the forerunner of European economic and monetary union. Even Lamont later admitted that “in his situation I might have behaved in the same way” during the crisis of 1992.

Helmut Schlesinger was born in Penzberg, a town near the Alps of southern Bavaria, as Germany emerged from the ravages of astronomical inflation in 1924 — a disaster that doubtless coloured his later views.

From high school he was conscripted into the mountain troops of Hitler’s Germany for the last two years of the Second World War. Thereafter he studied economics at the University of Munich, and in 1949 married his wife, Carola, with whom he had four children — Almut, Reingard, Gertraud and Stefan. Carola died in 2023.

Schlesinger earned a doctorate in 1951 and joined the Bundesbank, then known as the Bank deutscher Länder, the following year. A keen mountaineer in his spare time, he climbed rapidly through the ranks in his professional life as well.

In 1956, aged 32, he was appointed head of the Bundesbank’s economic analysis and forecasting division. In 1964 he was made head of its economics and statistics department, and in 1972 he joined its directorate. Eight years after that he became the bank’s vice-president, serving under Karl Otto Pöhl and making a point of climbing the 12 flights of stairs to the executive floor each day to stay fit.

If Pöhl was the elegant international face of the Bundesbank, Schlesinger was its “interior minister” and intellectual powerhouse. During the 1970s he had converted it to the cause of monetarism after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. In the 1980s he championed a stable currency, contributing to the collapse of Helmut Schmidt’s coalition government in 1982 by refusing to lower interest rates.

Indeed, he fought inflation with such zeal that James Baker, President Reagan’s Treasury secretary, once accused him of “looking for inflation under every stone”. Others called him “the Bavarian Prussian” and “stringent Schlesinger” to the “polished Pöhl”. One commentator described him as the Bundesbank’s “chief ideologue, a man whose heart beats to the rhythms of the anti-inflationary chants in this temple of monetary rigour”.

Calm, polite and professorial, but also obdurate and demanding, he explained his thinking in monthly Bundesbank bulletins that he edited himself, writing neat notes in the margins with a pencil.

Schlesinger never sought the Bundesbank’s presidency for himself, but he got it unexpectedly in 1991 when Pöhl resigned after Helmut Kohl, the German chancellor, ignored the bank’s warnings that the terms of Germany’s reunification would stoke inflation.

It did just that, and one of Schlesinger’s first acts a president was to raise Germany’s benchmark interest rate from 6.5 per cent to a record 8.75 per cent as inflation edged up towards 5 per cent. That caused a short recession in Germany. More importantly, it triggered the crisis within the ERM that led to Britain’s ignominious departure, severely damaged Major’s government and stoked British Euroscepticism.

Schlesinger retired from the Bundesbank the following year, by which time he was approaching 70. He received awards from several European countries and honorary doctorates from various European universities — but none from Britain.

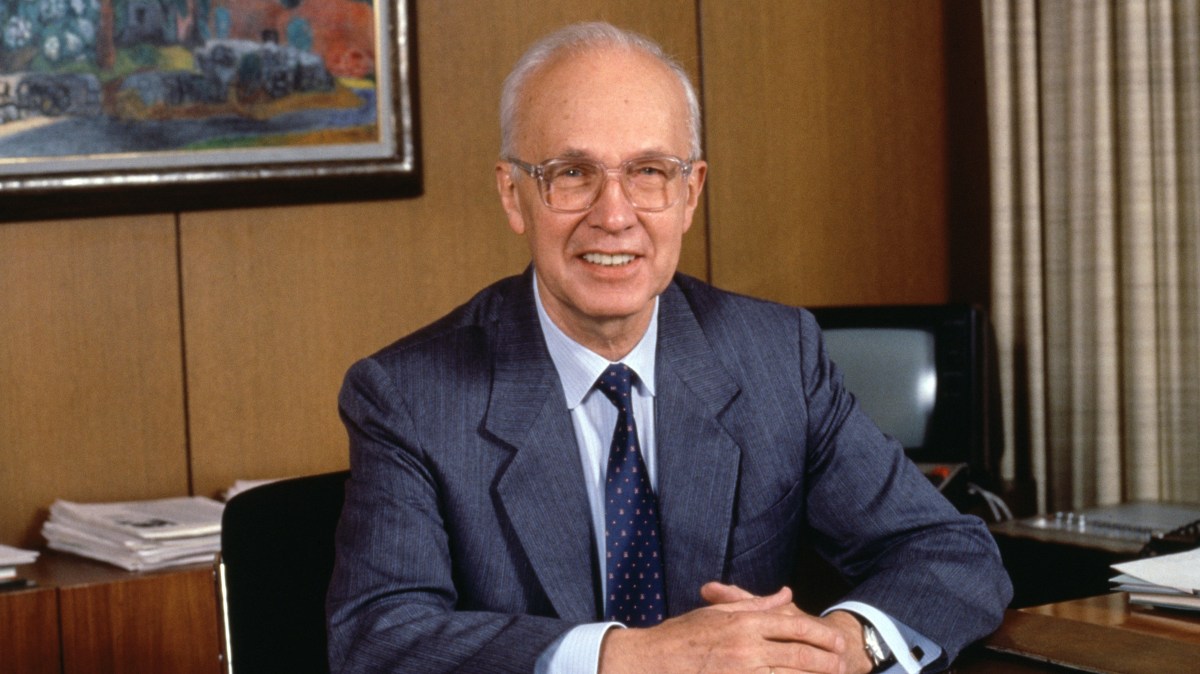

Helmut Schlesinger, president of the German Bundesbank, was born on September 4, 1924. He died on December 23, 2024, aged 100