South Korea, one of America’s top-10 trading partners, has become one of the most high-profile targets of Washington’s shifting tariff regime. After months of tug-of-war diplomacy, the United States imposed a 15% duty on Korean imports effective August 7 – less severe than the 25% levy initially floated but still painful for Asia’s fourth-largest economy. In exchange, Seoul agreed to ramp up investment in US projects and pledged to purchase $100 billion worth of American energy products, a deal that was meant to soften the blow. Seoul has already quantified the potential tariff impact, forecasting just 0.9% growth for 2025 (compared to 1.8% at the beginning of this year). This would mark the weakest pace of growth since the pandemic in 2020, underscoring how vulnerable the country’s export-led model is to tariff shocks.

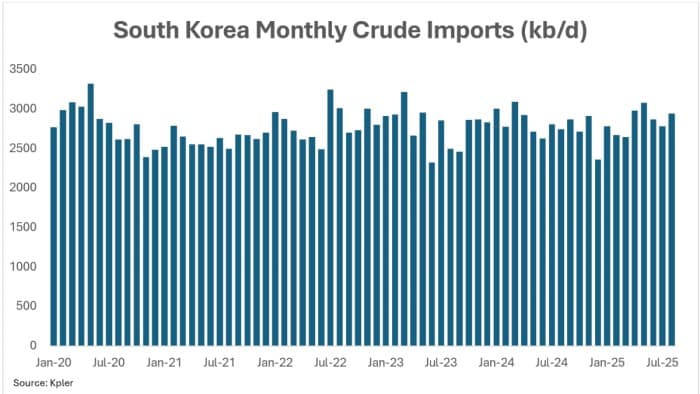

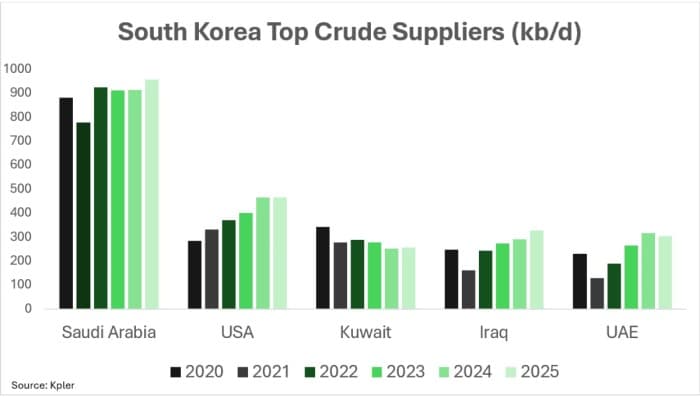

The energy pledge, however, looks harder to fulfil in practice than it is on paper. Washington expects South Korea to substantially increase imports of US crude, but refiners across the country have already been gradually shifting in that direction for years. According to Kpler data, imports of WTI Midland rose from 283,000 b/d in 2020 to 465,000 b/d in 2025, supported by favourable conditions under the bilateral free trade agreement and Korea’s freight rebate system that often makes WTI cheaper than Middle Eastern grades. Yet any incremental moves from here would be constrained. Total Korean crude imports have held steady in the 2.8 to 3 million b/d range for the past five years, and while American volumes have risen, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and the UAE remain deeply entrenched in the supply mix. Saudi Arabia alone delivered 956,000 b/d to Korea in 2025 to date, nearly double the volumes from any other supplier, and though Russian flows dropped sharply after the start of Ukraine war, the gap was quickly filled by other Middle Eastern producers.

What keeps these flows in place is not just habit or geopolitics, but the underlying design of Korea’s refining system. WTI is a light crude, while South Korea’s highly complex refineries are configured to process heavier grades, predominantly Middle Eastern ones. Shifting too heavily toward US barrels (and subsequently, toward a lighter product yield) would leave parts of these facilities idle, eroding efficiency and profitability. Korea operates five refineries, and each illustrates why diversification is easier said than done. The largest, Ulsan, fully owned by SK Energy, already blends WTI with heavier grades from Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia to run at capacity. Yeosu, half-owned by Chevron, follows a similar pattern, comingling rising volumes of WTI with heavier Iraqi barrels. Onsan and Daesan refineries, partially owned by Saudi Aramco with stakes of 63% and 17% respectively, lean overwhelmingly on Arab Light and Arab Medium, together making up about 80% of their crude slate. With Saudi interests directly embedded in their ownership structure, any push to substitute American crude faces resistance. Meanwhile, Incheon, the smallest refinery, struggles to operate even at 50% capacity and faces operational constraints that leave it in no position to absorb excess light oil.

Even in refineries that could handle more WTI, the economic rationale has weakened. Light crudes like WTI yield larger amounts of naphtha, a feedstock for the petrochemical industry. But global oversupply, fuelled by relentless Chinese capacity expansion, has created a petrochemical glut. Margins have collapsed, and on August 20 South Korean petrochemical companies announced a collective 25% cut to the country’s naphtha-cracking capacity. For refiners, naphtha cracks have been consistently negative, meaning that buying more light crude would not only strain refinery configurations but also risk churning out products that have no profitable market.

Layered on top of these operational limits are the contractual obligations that tie Korea to Middle Eastern suppliers. Unlike American producers, who sell mainly on spot terms, Saudi or Iraqi exporters prefer long-term contracts with little flexibility. Failure to lift agreed volumes risks penalty or even termination, a strict policy that reflects the abundance of global demand for their barrels. In practice, this means Korean refiners cannot simply displace Middle Eastern grades without risks to their supply security in order to accommodate Washington’s demands, however strong the diplomatic pressure may be.

Related: US Oil Drillers Continue to Play It Safe

The tension between politics and market realities became clear in June, when South Korea’s Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy convened an emergency meeting with crude and LNG importers after the Israel–Iran crisis escalated. The government used the moment to urge refiners to diversify away from their deep reliance on Middle Eastern crude, arguing that regional instability underscored the risks of overdependence. Yet even this direct warning failed to alter behaviour: imports continued to flow overwhelmingly from the Middle East, with only incremental increases in US volumes.

For now, Seoul is edging toward a middle course, raising US crude imports at the margins while relying on its entrenched heavy grades from the Gulf. But the deal struck under tariff pressure exposes an uncomfortable truth: South Korea cannot satisfy Washington’s demands without undermining the very foundations of its refining system and petrochemical industry. Heavy reliance on Middle Eastern supply is locked in by refinery design, contractual obligations, and ownership stakes.

South Korean Refineries

Refinery

Ownership

Capacity (kb/d)

Ulsan

SK Energy 100%

840,000

Yeosu

GS Caltex

(GS Energy 50%, Chevron 50%)

785,000

Onsan

Saudi Aramco 63.7%, South Korean Government 7.3%, Free float 29%

669,000

Daesan

Hyundai Heavy Industries 74%, Saudi Aramco 17%, Hyundai Motor 4.4%, Others 4.6%

520,000

Incheon

SK Energy 100%

275,000

That leaves Seoul caught between a rock and a hard place, vowing to please its most important ally by buying barrels it cannot fully use, or preserve the operational logic of its energy system and risk further trade retaliation. In practice, the likeliest outcome is that Korean refiners will marginally increase US purchases, blending those extra WTI barrels with heavier Middle Eastern grades, a compromise that secures refinery balance but falls short of Washington’s ambitions. Either way, the price of accommodation is high. South Korea’s case is a poignant reminder that, as much as politicians seek to force deals, they cannot rewrite the laws and economics of refining.

By Natalia Katona for Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com