In a basement office in Damascus, three middle-aged Syrian dentists are smoking and drinking Turkish coffee before heading into what they call the “rooms of bones”.

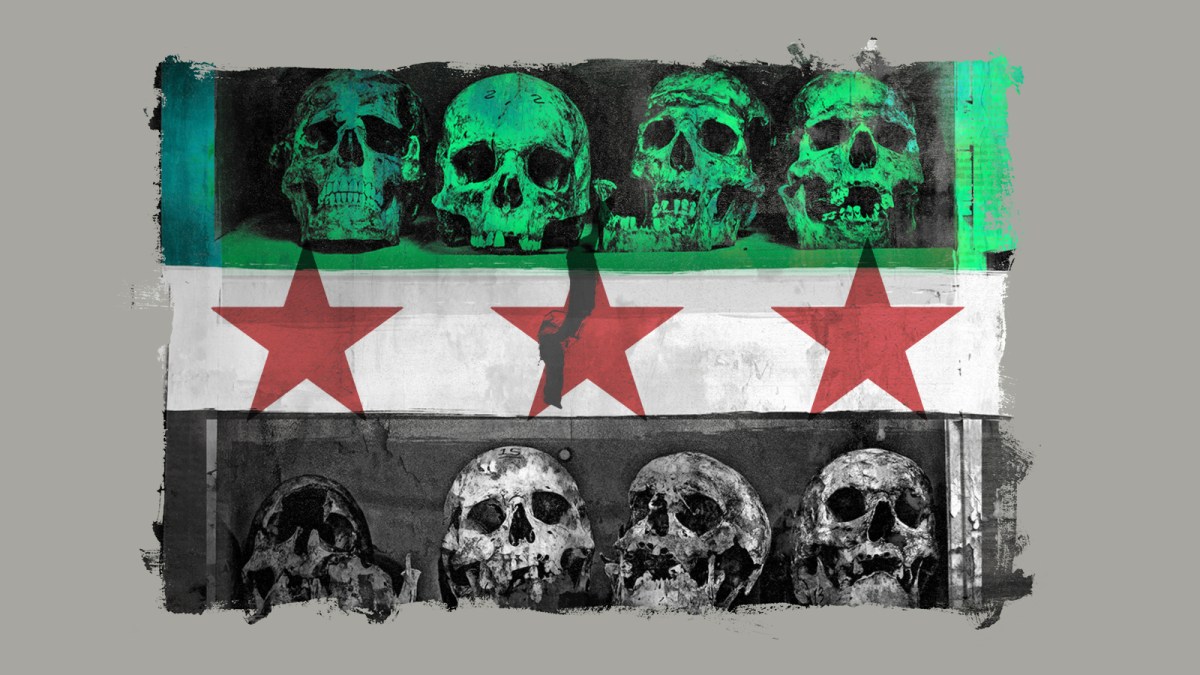

There, on two long tables, are lines of yellowing fibulas and femurs, each carefully numbered. In the next room is a series of lockers. Dr Anas al-Hourani opens one to reveal shelves of skulls, most bearing holes in the back of the head from bullets. “Executions at close range,” he said.

“Bones tell us the story of a person,” said his colleague, Dr Ahmad Naim, holding up one of the fibulas and checking the ends for fusion to see if it belonged to a child. He measures it and consults a textbook on forensic anthropology to determine age, height and sex.

Dr Anas al-Horani, left, Dr Ahmad Naim and Dr Aaamer al-Sarajiby, right

GABRIEL CHAIM FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

Anatomy aside, the stories are horrific. These bones are from some of the tens of thousands of demonstrators and activists detained, tortured and dumped in mass graves by the security apparatus of Bashar al-Assad between the start of the revolution in March 2011 until he was toppled last December.

Another room has a pile of burnt clothing and a skeleton reassembled from one of 50 zip bags of jumbled bones recently brought in by the White Helmets, Syria’s rescue organisation. The remains had been found in a basement of an abandoned building near Sbeneh checkpoint, south of Damascus, where regime forces would routinely arrest people, kill them and burn the bodies.

“Our job is to turn the codes on the zip bags into human beings with achievements and dreams,” said Hourani. Among the 50 sets of remains were four women, two children of 12 and 17, and the rest all men over 25. So far they have identified only ten. Most had been shot in the head at close range. Some had broken bones.

GABRIEL CHAIM FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

“It’s like we’re reliving the horrors every day,” said Naim. “While the rest of Syria celebrates the liberation, we’re still in the middle of the war, having daily flashbacks of the evil of those 14 years.”

These dentists, who earn $30 a month working for the health ministry identification centre but also work in their own private dental clinics, are charged with identifying one of the biggest groups of missing people in recent times.

• Secret Assad files show Stasi of Syria put children on trial

The Syrian Network for Human Rights has documented more than 155,000 missing but according to Mazin al-Balkhi, Syria director for the International Commission on Missing Persons, the total could reach as many as 700,000. He points out that his own family has 22 missing members who have not been reported. “Every day we find a new mass grave,” he said, “78 so far. Dealing with this could take decades — Syria does not have the capacity or forensic experts.”

With no DNA analysis available in Syria — there is only one small laboratory and the necessary chemicals are not allowed in because of sanctions — dental records are the main method for identifying people. “Even when bodies are burnt the teeth are preserved and that’s why you need dentists,” explained Hourani, “though we are odontologists — dentists experienced in bones.” He holds up a tooth. “This is the third molar, depending on its roots we can determine the age of a person.”

In the whole of Syria, there are only 25 forensic odontologists, including these three. They work by taking measurements then consulting textbooks and internet resources — a painstakingly slow process.

The information is loaded into a database that Naim has designed, comparing it to the details of 35,000 missing people provided by the families to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which supports the centre. “Whole corpses are easy,” he said. “The problem is when bones are mixed, then it can take three weeks to sort them and identify. Until we have more odontologists we can’t take more than ten cases a day.”

Dr Anas al-Horani, left, and Dr Ahmad Naim inspect a skull with a bullet hole

GABRIEL CHAIM FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

The problem is, after years of silence when many relatives did not even report missing ones for fear they too would be arrested, people do not want to wait. “When liberation happened everyone in Syria thought they would get their family members back,” said Dr Aaamer al-Sarajiby, who runs the office.

After Al Jazeera broadcast live from a mass grave, hundreds of families rushed there and began digging into the earth with their fingernails. “It was a mess,” said Balkhi. “These are crime scenes.”

Within hours of Assad’s fall, the prisons were opened, including Sednaya, the most notorious, described by Amnesty International as a “human slaughterhouse”. In its fridge were 36 recent corpses.

The three dentists were called at 3am to go to the morgue in al-Mujtahid Hospital in Damascus to try to identify them. They found the place besieged by hundreds of families. “Imagine every single person in Syria thought maybe one of those bodies is my son or husband and they all came there,” said Hourani. “At that point there was no security, no state, just total chaos. Three of the bodies were seized by families before we could even do anything.”

Mazen’s story

One of those they did identify was a man thought to be the very last victim of the Assad regime, Mazen al-Hamada. Arrested in 2011 and brutally tortured, he was released in 2013 and given asylum in the Netherlands, from where he toured western capitals, often in tears as he showed them his scars and told of his rape and torture.

Yet he had been lured back to his homeland in 2020, apparently persuaded by the Assad regime that officials would release his elder brother and brother-in-law. Instead, they arrested him.

Mazen al-Hamada appeared in the 2017 documentary Syria’s Disappeared: The Case Against Assad

At a ceremony last month at the ancient monastery of Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi (St Moses the Abyssinian), high up in the mountains of the desert, 60 miles northeast of Damascus, his sister Amal Hamada, 58, dressed in black, planted a cross with his name on it in an olive grove.

“I begged him not to come back but he felt he didn’t have a choice,” she said. “They had started threatening him in Holland and also said they would arrest the rest of our family. He also was frustrated that after all these efforts Assad did not fall, and felt the international community was doing nothing.”

When he arrived at Damascus airport, he called to tell her and asked her to come with $400 that the person with the phone was demanding. “I got a cab to the airport at 2am but couldn’t find him anywhere. Eventually one man told me four officers from the air force intelligence branch had come and arrested him.”

He was taken to various detention centres, ending up in Sednaya, where she heard from a fellow prisoner who had been released that he was in solitary confinement and undergoing repeated torture. “They were asking him to go on Syrian TV and say everything he had said in Europe was lies, that there was no torture,” she said.

“We think he was killed just a week before liberation. When Sednaya was opened we saw a picture of his body in the media with another 35 men in the fridge. The regime had fallen before they could dump them in a mass grave. When we went to the hospital and saw his corpse, his whole body was broken, fingers, ribs, everything.”

“I hope he knows Syria was freed,” she said.

Amal was one of about 40 family members of the disappeared telling the story of their loved ones and planting crosses, as long shadows fell over the monastery’s sandstone walls and a crescent moon emerged in a purple sky. The only sound was birdsong and occasional sobs.

The fate of the missing is one of the priorities of the new administration of President al-Sharaa, who, in May, created a National Commission for Missing Persons and another for transitional justice. So far 78 mass graves have been identified, some with trenches as long as 300 ft and 13ft deep, packed with bodies. There are even mass graves in the capital.

Meet the bone ‘expert’ — he’s 12

Much of the neighbourhood of Tadamon in southeast Damascus was flattened in fighting between the regime and rebels of the Free Syrian Army.

Wandering the ruins today are two boys, Yusuf, 12, and his ten-year-old cousin Mahir, who holds up what looks like a tibia. They offer us a tour, and summon a friend they call “the expert”. Musa, also 12, has hands covered in black grease from his job as a mechanic.

GABRIEL CHAIM FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

GABRIEL CHAIM FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

They lead us to a destroyed building where they say in 2013 Assad’s men blindfolded prisoners, including two of the boys’ uncles, and told them to run from a sniper, only for them to fall in a pit and be shot. A video of this was smuggled out in 2022, showing 41 people killed, including women and children, bullets thudding into their flailing bodies as the commander, Amjad Yousuf, laughs.

Yousuf’s unit is said to have carried out dozens of such massacres in the area, and crunching through the rubble, the air fills still with horror. “The dead bodies walk at night,” says Mahir.

With no capacity to deal with these graves, the areas are supposed to have been sealed. The boys tell us that the Turkish Red Crescent recently came and took some of the bodies but they keep picking up bones to show us. They lead us to a place with a boy’s shoe and a putrid smell. A pack of dogs lurks.

Every building is peppered with bullet holes or concertinaed by airstrikes yet we come across a surreal tableau of a gilt and velvet sofa and two armchairs on a pile of rubble. In the midst of the ruins someone has also constructed a breezeblock dwelling with a garden. “It’s hard to sleep here,” admits a man who arrives on a scooter with two children and walks in the door. “I’m sleeping and under the ground are bodies of innocent people.”

‘It’s not easy to go from this evil to filling cavities’

Back at the identification centre, the dentists are depressed. “We were waiting for this day,” said Hourani. “Under the regime, if a body was found, courts had to give permission for us to identify and mostly they did not. But there was so much talk of mass graves, we knew this was coming, particularly after the Caesar photos were leaked.”

He is referring to a graphic archive of more than 28,000 photos of deaths in government custody, smuggled out of Syria in 2014 by an activist codenamed Caesar. Like the Nazis, the Assad regime documented everything.

Sometimes a family came with one of the photos and begged them to help identify a son. “If the regime had known what we were doing we would have ended up among these bodies,” said Naim.

Now their moment has come, but confronting the reality of Assad’s machinery of death up close every day, is, says Sarajiby, “devastating”.

The ICRC sent experts from Peru, Argentina and Bosnia, which also suffered large numbers of disappeared, to help advise on the methods and how to deal with traumatised families but the dentists say no one thinks about their own trauma. “We’re under enormous psychological pressure,” said Naim. “The families need to know what happened and we work day and night but it will take decades and seeing such horrors up close is hard to take.”

All of them lost relatives and friends and wonder whether the next body will be someone they know. “It’s also not easy to go from all the evil here to gently filling cavities for people in our dental clinics,” said Sarajiby.

On top of everything else, they have been getting new bodies — 40 from Sweida, the southern city where more than 1,400 people have been killed in recent clashes between the Druze and the Bedouin and by government forces.

“It never ends,” said Hourani.