Jean-Claude Leners could actually be enjoying his well-earned retirement. The general practitioner worked in Ettelbrück for 44 years. He specialised in geriatrics for 25 years of his career. “I was one of the first in the country to be licensed to do this,” he told Télécran.

But instead of kicking back, he still makes house calls with elderly patients, visits retirement homes and cares for patients with dementia, a cause particularly close to his heart. Until six months ago, he also worked in palliative care at Haus Omega.

Just five years ago, he completed a master’s degree at the renowned Karolinska Institute in Sweden, specialising in dementia care. “The care requirements vary considerably depending on the stage of the disease. You’re not completely dependent and bedridden from the start,” Leners said.

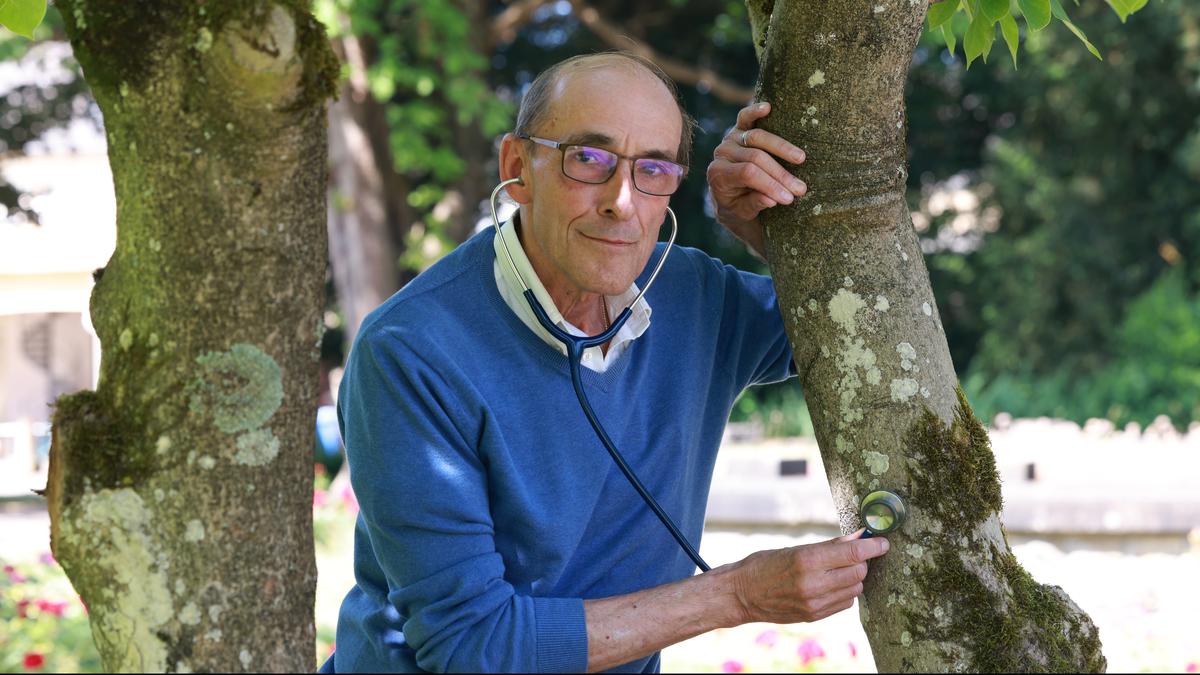

Every two years, Jean-Claude Leners goes on a humanitarian mission, usually to Asia. © Photo credit: Anouk Antony

35 years of humanitarian missions

Leners helps care for Luxembourg’s elderly but also some of the world’s poorest patients. For 35 years, he has travelled on humanitarian missions with medical aid NGO “German Doctors” for six weeks every two years. The organisation from Bonn sends doctors on voluntary missions to medically underserved areas, including Kenya, Uganda, India, Bangladesh, Sierra Leone and the Philippines.

His most recent mission to date took him to Mindoro, the seventh-largest island in the Philippines, where he worked alongside local healthcare staff in so-called rolling clinics, jeeps full of medical equipment used to reach remote villages.

The convoys struggle for hours through rivers, mud and over steep slopes to reach the Mangyans, the umbrella term for eight indigenous population groups in the southwest of the island. Each of these groups has its own tribal name, language and customs, and local translators are indispensable.

“You can see that these people live in completely different conditions to those in the cities, where there are certainly good hospitals,” Leners said. The Mangyans live in seclusion, often lack the financial means for transport to the nearest hospital and have no health insurance. Many illnesses remain undetected until Leners and his colleagues come to them.

No matter what mission you are on, you are always well received

Jean-Claude Leners

Open-air clinic

The working conditions are anything but luxurious. Up to 100 patients are treated every day in a small hut that doubles as a clinic. More often than not, the team simply set up on a local sports court: “We pitch our tent where people usually play. Sometimes parties are held there, so we can’t work,” Leners said.

There are wooden benches and a table, and sometimes a canopy to keep out the rain. Working in the middle of the hustle and bustle of the village brings its own challenges, as there is a lack of discretion.

“If someone has a problem with their private parts and needs to undress, we at least put a cloth over them to protect them from the neighbours’ eyes.” It can get loud when children are running around or street dogs are barking. “If I then want to listen to people with a stethoscope, it’s sometimes difficult,” he said.

Tuberculosis, worms and the limits of help

The Mangyans suffer from a wide range of diseases that are often linked to their living conditions. Tuberculosis, for example, is widespread as people live together in very confined spaces. Intestinal diseases caused by worm infestation are also more common as the water is contaminated.

“It’s a never-ending story that repeats itself until hygiene conditions improve,” Leners said. Open wounds from working in the fields and respiratory diseases caused by cooking over an open fire are also part of everyday life.

But the Mangyans are also affected by typical old-age or common diseases that occur in Europe: “In the Philippines, there are a lot of people with high blood pressure or diabetes. Young people are also affected, but mainly people over 60, partly because they don’t get enough exercise. Working in the fields is one thing. The other is to actually go for a walk.”

The team has to make do with around 30 medications, the quantity is adjusted depending on the country and region, but larger quantities are required for long-term therapies. “You can only hope that people take the medication correctly. There is no follow-up appointment like in Luxembourg.” In serious cases such as tumours, his hands are tied: “I can only prescribe morphine or organise transport to hospital,” he said.

Without a translator, Jean-Claude Leners would not be able to communicate with the Mangyans © Photo credit: Private

A table and a few chairs often have to suffice as an infirmary © Photo credit: Private

The infirmary in the Philippines is minimally equipped © Photo credit: Private

The team has to make do with around 30 medicines, the quantity depending on the country and region © Photo credit: Private

Up to 100 patients can be seen every day © Photo credit: Private

Without a translator, Jean-Claude Leners would not be able to communicate with the Mangyans © Photo credit: Private

Between danger and hospitality

“The joy of the locals is infectious,” Leners said. “No matter what mission you’re on, you’re always well received. They have adjusted to me within 24 hours. They are always friendly and jovial.”

There is a basketball hoop and karaoke machine in every village, no matter how small, Leners said. “If you can’t find these two things, you’re not in the Philippines. And if you are invited to karaoke, you should sing along, otherwise you won’t be accepted.”

But not all missions are so peaceful and harmless. He remembers a mission eight years ago to Mindanao, the second-largest island and its southernmost archipelago, which had to be terminated after the Islamist terrorist organisation Abu Sayyaf carried out several attacks. On Mindoro, on the other hand, he feels safer: “Nowadays, we are informed in good time by the mayor if there are any riots.”

Memories of India

Missions in India and Bangladesh are also etched in his memory, with the gap between rich and poor particularly wide there. One of his first missions was in India, in Kolkata. “Already 40 years ago, almost 20 million people lived in a very small area there. Back then, there were cases of leprosy and every second child was malnourished,” Leners said.

The infrastructure has since improved. “Today, women are supported in giving birth in hospital. The babies receive immunisations there and have access to health insurance. But not all families take up these offers. Some prefer to stay in their neighbourhood and wait for us, so to speak.”

Looking ahead

The recent mission to Mindoro is likely to have been his last one, but he’s not making any promises. He is not ruling out smaller missions in the future, but he is phasing out many tasks in order to give younger colleagues a chance and to spend more time with his family. “They have sacrificed a lot to enable me to take part in these missions every two years,” Leners said.

His wish is to inspire other doctors. “I realise that many are overworked and have a family. Nevertheless, I can assure you that you grow personally on such missions.” The trips teach you to appreciate your own profession more because you have to make do with very little, he said. “When you come back to Luxembourg,” he said, “you realise that we often complain about banalities here. We should realise more often how good we have it.”

(This story was first published in Télécran magazine. Translated using AI, edited by Cordula Schnuer.)