Germany blocked Russia’s Nato bid, documents reveal | Previously unseen confidential documents show how Bill Clinton’s plan to build military alliance ‘from San Francisco to Vladivostok’ collapsed — following Germany’s fierce objections to ‘revolutionary’ project

https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/geheimdokumente-wie-helmut-kohl-eine-nato-mitgliedschaft-russlands-hintertrieb-a-e28ff00c-0674-4806-a536-641249f462dc

Posted by 1DarkStarryNight

4 comments

Honestly the idea that Russia could be easily introduced to the western world after one of the most painful shock therapies the world has ever seen is so naive. Yeltstin had the Supreme Soviet shelled just the year prior, it wasnt working. And it was clear that a lot of Yeltsin choices had the US backing them

It would have been the most powerful military alliance in the history of mankind: from San Francisco to Vladivostok, with command over almost all the nuclear weapons that existed in the world.

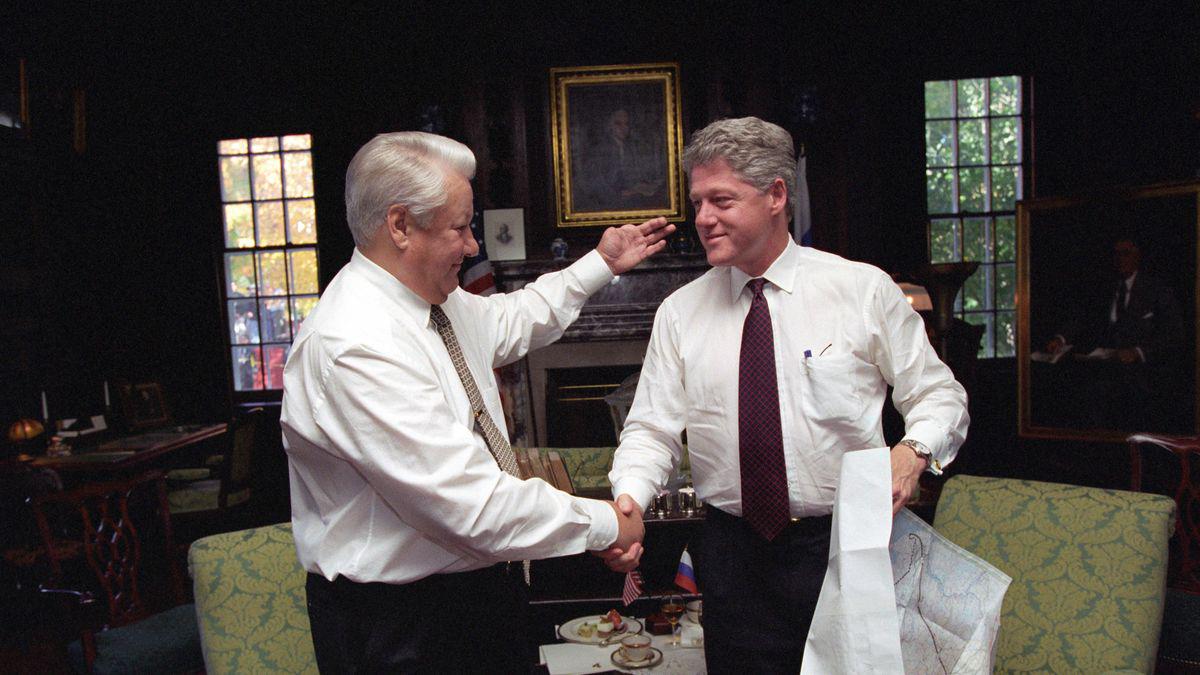

“Boris, one last thing, this is about NATO . I want you to know: I have never ruled out Russia’s membership. When we talk about expanding NATO, we mean inclusion, not exclusion” remarked US President Bill Clinton. And he added: “My goal is to work with you and others to create the best possible conditions for a truly united, undivided, integrated Europe.”

“I understand,” Yeltsin replied, “and I thank you for what you said.”

The memorable US-Russia summit took place in September 1994. Five years later, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary joined the Western alliance, followed by eleven other European states as part of the eastern enlargement. But Russia, was not among them.

So what was going on when the US President once discussed Russia’s accession to NATO with his visitor? Was this idea serious, as Clinton asserted after the Russian attack on Ukraine in 2022 : “We’ve always left the door open”?

SPIEGEL has analyzed confidential German documents from 1994, the year the NATO members made the fundamental decision to admit states from the former Warsaw Pact . The documents come from the private collection of one of the participants and from the collection of files regularly published by the Institute for Contemporary History on behalf of the German Federal Foreign Office (AA). They include letters from Chancellor Helmut Kohl (CDU) to Clinton, reports from German diplomats in Moscow and Washington, and internal documents for Foreign Minister Klaus Kinkl.

According to the documents, Clinton was serious about the Russia option. This was the “official US position,” reported German envoy Thomas Matussek from Washington in 1994. Clinton, a cheerful Southerner with an optimistic disposition, believed that his—the new—generation had a special responsibility to shape the future. And he believed that the Cold War had shown that almost anything is possible.

At that time, the US government repeatedly discussed the possibility of Russian accession with its allies, for example, on January 15 at NATO headquarters in Brussels. US Special Envoy Strobe Talbott, a Russia expert, college friend of Clinton’s, and his most important advisor on eastern expansion, had arrived there. Talbott informed the assembled NATO ambassadors of Clinton’s position. The German representative subsequently wrote that if the alliance followed the US approach, the question of Russian membership would arise “in just a few years.” A few weeks later, a German diplomat reported from Washington that Talbott had specified a time frame—it could begin around 2004.

The Germans met with high-ranking representatives from the US State Department, the White House, the Pentagon , and the CIA . They explained that it was unclear to them why Clinton had “not long ago revised” his stance on Russia’s NATO membership. “Remarkable,” commented a German embassy official.

When it came to Russia’s NATO membership, the German government was as flexible as concrete. Russia’s admission would be a “death certificate” for the alliance, complained Defense Minister Volker Rühe.

“Russian accession would mean the end of the alliance as we see it.” This fundamental objection could not be refuted. Berlin explicitly saw no place in the alliance even for a secure, democratic Russia.

However, Kohl and Kinkel did not want to alienate the Kremlin. A working group composed of staff from the Chancellery, the Federal Foreign Office, and the Ministry of Defense drafted a policy paper that was sent as a circular to all Bonn missions abroad in November 1994. It states: “Russia cannot become a member of either the EU or NATO. However, public statements should be avoided out of consideration for the desired agreements with the Moscow leadership.”

When Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev once pressed his German counterpart about what spoke against his country’s membership, Kinkel resorted to an excuse: NATO was only “currently” unready for Russia’s accession. This is what the new documents state.

Kohl, however, was spared the unpleasant NATO topic in phone calls and meetings with Yeltsin, as Joachim Bitterlich, the Chancellor’s most important foreign policy advisor at the time, testifies. Yeltsin presumably didn’t bring it up because he considered only the Americans important on this issue. Kohl also remained silent on the matter. “Spiegel once described me as the last dinosaur ,” he told Clinton at the time, “and if that’s true, I should tread carefully.” Dinosaurs don’t always have to be in the front row.

The spectacular idea originally came from the Kremlin. Yeltsin first expressed his interest in NATO membership on December 20, 1991. These were the last days of the Soviet Union, which was set to dissolve at the end of the year, and as president of the new Russia, he wrote to Brussels that he was ready to consider membership “as a long-term political goal.” The proposal fit the spirit of optimism: Russia had “sniffed the air of democracy and felt freedom,” and it would become “a different country,” Yeltsin promised.

When Poland, the Czechs, and Hungary pushed for the alliance a year and a half later, Yeltsin’s Foreign Minister Kozyrev asked the Americans to please treat the Russians the same way they treated the other new democracies.

Russia experts at the German Foreign Office attested to his orientation toward “Western ideals” — democracy, human rights, the development of new security structures.

He was promoting “Russia’s integration into European and transatlantic institutions.” In his memoirs in 2019, Kozyrev wrote that the question of NATO membership was, for his government, “the litmus test for whether the alliance was fundamentally opposed to Russian interests.”

From Moscow’s perspective, there has been a “basic understanding” since the talks on German unification in 1990, as the Foreign Office put it in 1994: “SU/RUS will relinquish its control over the area up to the Elbe and withdraw its military presence from the entire region. In return, the West will not exploit this politically or militarily; the European security architecture will be built jointly in an equal partnership.”

The Kremlin felt it had upheld its part of the “basic understanding.” In 1994, Russian troops withdrew from Germany, Estonia, and Latvia.

In January 1994, during a trip to Europe, Clinton declared that NATO expansion was no longer a question of if, but of when and how. When the US President subsequently flew to Moscow, Yeltsin suggested that NATO should admit Russia as the first country. Clinton was not committed to the order of priority, but agreed in principle to Russian accession, as Talbott reported to the allies soon afterward. German diplomats immediately countered: “We have advised the Americans against encouraging considerations in Russia that point in this direction. It can’t be allowed”.

Russia’s membership in NATO thus became a distant prospect. From then on, it seemed like a transparent attempt to reconcile the Russians with the impending membership of Poland and other countries in the alliance – which failed. As early as November 1994, Russian diplomat Yuri Ushakov complained that eastern expansion was “a kind of betrayal.”

It is the same Ushakov who is negotiating for Putin today about the Russian war in Ukraine.

Good. As it should be.

Based Germany for a change.

The russians had never really given up on their imperialistic tendencies (though, obviously, under putin way worse than under Yeltsin), so letting them into NATO basically destroys NATO.

It’s insanely naïve to think that just playing along with russia will suddenly make them all nice and Westernised.

NATO is a US-run alliance. There wasn’t really room for another major power which would have asserted it’s independence, within the alliance.

Really we have to ask if NATO was even needed after the collapse of the Warsaw pact and the Soviet Union.

I think Gorbachev’s idea of a common security architecture from Lisbon to Vladivostok was a good one. I don’t think you can exclude Russia from European affairs .But it has always been a US goal to prevent such integration.

Comments are closed.