They fired the old man.

OK, maybe technically they didn’t fire him, they simply eliminated his position, but it sure feels like a firing. We don’t know whether the old man got a buyout or not. If the company is smart, and wants to avoid an age discrimination lawsuit, it better have given him one.

You know which old man I’m talking about: the old fellow in the Cracker Barrel logo, who has now been replaced (along with his barrel) with what the company says is a fresher look as it struggles to reach beyond an older, and declining, customer base.

The backlash was swift. The company’s stock tanked on Wall Street (who knew the old-timer known as “Uncle Herschel” was so popular with investors?) and the corporate rebrand quickly became a political issue.

The president’s son, Donald Trump Jr., posted on X: “WTF is wrong with @CrackerBarrel??!”

U.S. Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, posed the question of which was worse: Cracker Barrel ditching the old man or Land O’ Lakes removing the image of the Native American woman from its logo. Hillsdale College, a private school in Michigan, compared the removal of Uncle Herschel with the vandalism of a statue of George Washington: “Same energy.”

The liberal news site The Daily Beast weighed in with “MAGA Mocked for Insane Cracker Barrel Logo Meltdown.”

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat whose office has taken to producing parodies of Trump tweets, sent out an all-caps post poking fun at the whole thing. The Salem Red Sox, who plan to announce a new name and logo in November, spoofed the whole thing by posting a Cracker Barrel-themed version of their current name. Yes, it was both hideous and hilarious. “Give the person who runs Facebook a raise for this one,” one fan commented on the team’s social media feed. Then on Tuesday, President Donald Trump himself weighed in (pro-old man) and, coincidentally or not, Cracker Barrel announce it would reinstate Uncle Herschel. The company’s stock promptly shot up.

I’m not inclined to put on a red baseball cap (instead, I have a nifty powder-blue Cardinal News cap, which you, too, can buy in our merch store). However, let me gently suggest that MAGA faithful and Wall Street investors shouldn’t be the only ones concerned about what Cracker Barrel has just done. Here some aspects to the Cracker Barrel logo change I haven’t seen addressed elsewhere.

1. This is another sign of the declining influence of rural America.

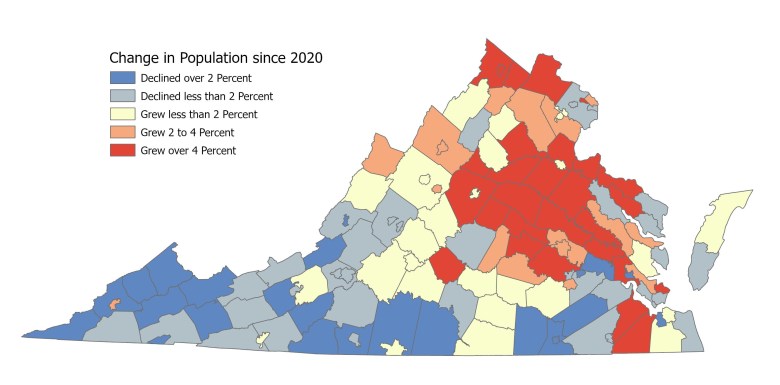

How Virginia’s population has changed from 2020 to 2024. Courtesy of Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, University of Virginia.

How Virginia’s population has changed from 2020 to 2024. Courtesy of Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, University of Virginia.

At least when Land O’Lakes retired the Native American woman as cultural appropriation, it kept the lake. Here a corporate logo that conjured up imagery of rural America has been replaced by just a graphic design. On the one hand, companies often change their logos and if Cracker Barrel thinks this logo will make its restaurants more appealing in the marketplace, well, that’s just business. Nothing personal, Uncle Herschel. Some of us might get worked up that a rural image has just been expunged from the corporate landscape, but this was hardly the first. Levi’s logo once included two horses; they were put out to pasture — or sent off to the glue factory — a long time ago.

More seriously, though, there are more things we’ll have to get used to than a corporate logo getting changed. The most recent population projections from the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service forecast that Southwest and Southside Virginia will lose population over the next 25 years, with some counties losing a quarter or more of their population and one — Buchanan County — losing nearly half its population. In Monday’s column, I looked at how these population projections will force changes to the state’s congressional maps. In Thursday’s column, I’ll look at how many seats in the General Assembly rural areas will lose. I’ll give you a hint now: It’s a lot.

2. Democrats once again miss an opportunity to connect with rural America.

Many of Trump’s policies do damage to rural America, and I’ve written about those: Check out this column about how rural communities are most at risk of retaliatory tariffs. Trump, though, understands symbolism better than many, and the Cracker Barrel logo is an example. For Trump to speak out about the logo is very on-brand. Liberal commentators seemed to think the hub-bub over the logo was all very silly. In many ways, it is, but people can identify with Uncle Herschel in a way that they can’t connect with some faceless policy decision. The left missed an opportunity here, even a symbolic one. More seriously, real-life blue-collar white men are a key Trump constituency, one that Democrats used to have and are now trying to figure out how to win over again. If Hillary Clinton had run just a wee bit better with those voters in 2016, she’d have won that election. If Kamala Harris had run stronger with them, she’d have won in 2024. Virginia Democrats don’t have to worry about that so much as long as they can run up the score in Northern Virginia, but they do not to worry some. Terry McAuliffe won overwhelmingly in Northern Virginia in the governor’s race four years ago, but Glenn Youngkin goosed the rural turnout by record amounts, and that’s why he’s governor today.

3. Workers are being replaced by automation.

Uncle Herschel wasn’t replaced by a younger worker. He wasn’t replaced by his Gen X nephew Joshua with all his tattoos or his Gen Z niece Olivia with the tattoos and the nose ring. He wasn’t replaced by, God forbid, an immigrant. Instead, he was replaced by a design. In effect, Uncle Herschel’s job was automated.

This is happening all across the workforce. This is why it’s so hard for American presidents, be they Democrats or Republicans, to increase manufacturing jobs. They’re among the easiest ones to automate. This is one reason manufacturing productivity is up, while the number of manufacturing jobs is down. Nobody seems to have a good handle on how many jobs we’re talking about. However, multiple studies — by Goldman Sachs, the McKinsey consulting firm and the World Economic Forum — have warned that 30% of American jobs could be automated by 2030, if not by machines then by artificial intelligence. That seems high to me, but you don’t have to go far to see it happening. Walk into a McDonald’s these days and you’re likely to be greeted by a touchscreen ordering system. I was in a grocery store in Winchester a few years ago where there was a robot patrolling the aisles to look for spills and such.

There are economic reasons for this: Robots don’t call in sick. Robots don’t complain. Robots don’t unionize. There are also demographic forces pushing automation: A declining birth rate over the years has reduced the number of workers entering the workforce at the same time that a generation of Uncle Herschel’s age is retiring. Industries that once fretted about finding enough workers are now investing in robots instead.

4. Automation is creating more jobs than it eliminates, just not for Uncle Herschel.

Studies by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston University and the World Economic Forum say that automation will create more jobs than it eliminates — they’ll just be different jobs. If so, that’s similar to the North American Free Trade Agreement, which economists say created more jobs than it did away with — they were just different jobs and, most crucially, in different places. We’ve also seen this in the energy field. The transition to renewables has created jobs; they’re just not in the communities that are losing jobs as the demand for coal dwindles. In 2019, Joe Biden told a campaign audience in New Hampshire: “Anybody who can go down 3,000 feet in a mine can sure as hell learn to program as well. … Anybody who can throw coal into a furnace can learn how to program, for God’s sake!” That was widely regarded as tone-deaf to the concerns of coal communities.

Our proverbial Uncle Herschel just lost his job. Where’s his retraining program? Is there even employment available where he lives? Since he’s just a logo, this doesn’t matter. However, for lots of real, actual, living and breathing people, these are real concerns that neither party has found a good fix for yet.

5. Labor force participation is dropping.

The old Cracker Barrel logo showed Uncle Herschel sitting down, his arm resting on a barrel. He looks relaxed. He certainly doesn’t appear to be working at that moment. Maybe he’s on a break. Maybe it’s his day off. Or maybe he’s not working at all and is just hanging out. If so, Uncle Herschel speaks to not one but two trends regarding the labor force, both dealing with something called labor force participation. That refers to the number of people of working age who are either working or looking for work. There are always some people who aren’t in either group, especially women who might be home taking care of children.

Generally speaking, we like to see a high labor force participation rate. However, it’s been dropping over the years. The rate peaked in spring 2000 at 67.3%. The most recent figure, produced by the Federal Reserve, puts it at 62.2%. If you hear someone complain that “people just don’t want to work anymore,” there’s some truth to that. However, people Uncle Herschel’s age aren’t the problem. The Bureau of Labor Statistics says the biggest drop in labor participation from 2003 to 2023 came from young men, particularly young white men.

In 2003, the labor force participation rate for men 20-24 was 80%. Two decades later, it had fallen to 72.5%. While that’s still higher than the national average, the rate of decline is also the sharpest of any age cohort. The rate for women in that age group essentially didn’t change, but the rate for men sure did.

The labor force participation rate is lowest for those 55 and older — we’ll assume Uncle Herchel is in that age cohort — but it’s actually risen over the past two decades. In 2003, the labor force participation rate for men 55 to 64 was 68.7%; two decades later, it had edged up to 71.6%. For those 65 to 74, it went up from 26.4% to 31.0%. The rates for women were lower, but also went up.

When we look at those statistics through the filter of race, we see it’s white men who have exited the work force at the fastest rate. In 2003, white workers had a higher labor force participation rate than Black workers. By 2023, it was the other way around; Black workers had a slightly higher labor force participation rate than white workers. The rate for Black workers had stayed about the same; it’s dropped for white workers, pulled down by both men and women, but especially men. If Uncle Herschel were real, and Cracker Barrel wanted to replace him with a younger worker, age discrimination laws would be a problem — but so would economic realities. It might be hard for the company to find a suitable replacement. No wonder the company went the automation route.

Why has labor force participation for men declined? A report by the Federal Reserve cites multiple reasons: more men going to college (but often going at later ages) as well as decline in traditionally male-dominated jobs.

6. Labor force participation has always been lower in rural areas.

If Uncle Herschel is part of the labor pool — whether employed or unemployed — he’d be unusual in many rural areas. The map above shows how widely labor force participation rates vary across Virginia, from 78.2% in Alexandria down to just 35.3% in Buchanan County. The low participation rates in Southwest Virginia — often less than 50% — suggest a certain hopelessness about the economy and might also reflect the effects of opioid addictions, which started in Appalachia. (Cardinal’s Susan Cameron recently wrote about this in a three-part series.) Whatever the reasons, the low labor force participation rate also acts as a drag on the economy: Employers want to be places where they’re sure to find workers; why go to a part of the country where they may not be able to?

7. People are working longer — and might have to work longer in the future.

You’ll notice from the labor participation rates above that the percentage of people who are working while in their traditional “retirement age” years has gone up. That may not be an option in the future; it might be a necessity. Age 65 used to be the traditional retirement age for full Social Security benefits to kick in; now that threshold been raised to 66 years and 10 months for those born in 1959 or later. For those born 1960 or later, the age is going up to 67 years old and there’s repeated talk of raising it to 70. Some of this is driven by longer life spans, but mostly it’s about keeping the Social Security system solvent. When Social Security began, there were 159 workers for every beneficiary — the workforce was younger and people didn’t live long past retirement. By 1950, the rate was 16.5 workers paying for each beneficiary. The most recent reports say there are now 2.7 workers paying for each beneficiary, with the ratio still trending downward.

The French protest a proposed raise in the retirement age. Courtesy of Toufik-de-Planoise.

The French protest a proposed raise in the retirement age. Courtesy of Toufik-de-Planoise.

The United States isn’t the only country facing this problem. France tried to change the retirement age from 62 to 64, and the French responded the way the French often do: They protested so much the government had to back down. “Every French president for the past 40 years has attempted to change the pension system and retirement age, prompting anger and demonstrations against an assault on what is seen as the keystone of France’s cherished model of social protection,” The Guardian reports.

Canada’s solution is to promote immigration to attract more younger workers. Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush once advocated the same thing — “rebuild the demographic pyramid,” he called it — but he was swept aside by Donald Trump in the 2016 Republican presidential primaries and Trump had very different ideas about immigration.

The math, though, remains the same. If Uncle Herschel were real, he could probably start drawing some benefits now, but he’d be financially better off if he could keep working a while longer yet — but to make that happen, there needs to be work available, and work he’s qualified for.

8. Local companies are disappearing.

The real Uncle Herschel, on whom the logo was based, was a salesman for the Martha White Flour Company. You can still buy Martha White flour, but Martha’s not the one making the money. The brand was invented by a Nashville-based flour company in 1899. Today it’s owned by a Connecticut-based private equity firm. This is the same trend that has depleted many small cities of corporate headquarters over the years, with locally owned companies getting gobbled up by out-of-town ones. It’s why daily newspapers in Virginia are no longer owned by in-state publishers but out-of-state ones. It’s why Norfolk Southern, which started in Roanoke and then moved to Norfolk, is now in Atlanta. It’s why Advance Auto, which also started in Roanoke, is now in Raleigh.

9. Artificial intelligence is promising, but also fallible.

The basis for Cracker Barrel’s decision to get rid of Uncle Herschel is essentially that he’s too old (and too rural) to be a good image for the company. But how old is he, really? Not the age of the logo, but how old a man does the logo portray? To answer that question, I turned to artificial intelligence — and may have accidentally set some data centers in Northern Virginia on fire in the process.

The age.toolpie.com site says the old man appears to be 35.

The age.toolpie.com site says the old man appears to be 35.The internet is full of many things, including sites that claim they can figure out someone’s age from a photograph. Several said they couldn’t process the image from the Cracker Barrel logo because it wasn’t a real photo. Good for them, but others weren’t so squeamish. The site age.toolpie.com processed the image and reported that Uncle Herschel looked to be 35 years old. The site “How Old Do I Look?” said he was 39. I am skeptical, although maybe Uncle Herschel has had a harder life than he’s let on.

The “How Old Do I Look?” site says he appears to be 39.

The “How Old Do I Look?” site says he appears to be 39.

ChatGPT first told me it couldn’t tell, but concluded it was the face of someone “possibly middle-aged or older.” Upon further questioning, ChatGPT said he was “possibly over 40.” Being a good journalist, I kept pressing for something more specific. ChatGPT then said the image “likely represents someone in the range of late 50s to early 70s.” When I demanded even more specificity, ChatGPT replied: “If I had to give a number based on how he feels in the image (not a literal, photographic assessment), I’d estimate: Around 62 years old.”

Now we’re talking, although when an AI program starts using the pronoun “I” and talks about “feels,” I start thinking about the computer program HAL in “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

There is one final set of data available here: birth records. The first name “Herschel” did not appear in the United States until 1880, when 11 babies were given that name. The name peaked in the 1910s, hitting its high point in 1921, when 277 Herschels were born. By 2011, the name had almost died out, with just nine Herschels, although it’s enjoyed a very modest revival into double digits in the years since. Statistically speaking, Herschel could be more than 100 years old, which means he has probably earned the right to sit beside his cracker barrel.

We’re serving some up, fresher than snap beans just picked from the garden. We sent questionnaires to all the statewide candidates, all the candidates for the House of Delegates and all local candidates in Southwest and Southside. Find their answers, and see who’s on your ballot, on our Voter Guide. Early voting begins Sept. 19.

For more political news and insights, sign up for West of the Capital, our weekly political newsletter. It’s just like the gossip down at the old country store, only with attribution.

Related stories