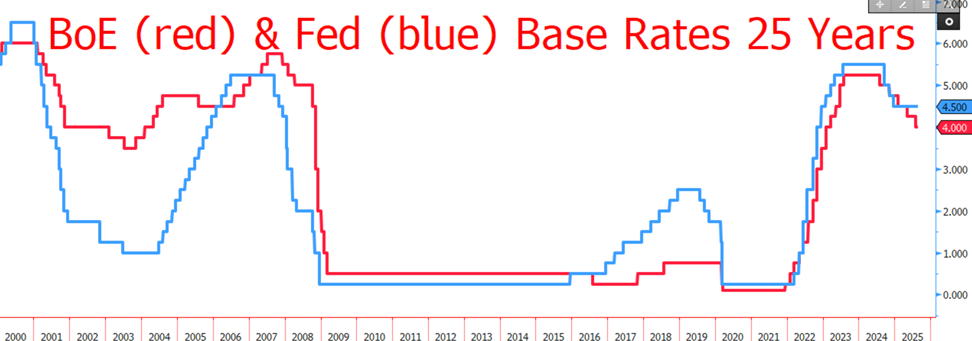

The Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have had to deal with similar problems over the past 15-20 years, with both being called into serious monetary action after a decade of ultra-low rates permitted by unusually low and stable inflation.

That calm was shattered first by the Coronavirus pandemic and then the Ukraine war followed up with the second jab to put that sleepy era finally to bed.

But time has come for the Banks to diverge, as the two economies start down seriously different paths. One has unemployment at multi-year highs, sliding consecutively this year, the other has relatively stable unemployment and is seeing a gradual cooling of conditions.

Both have rising inflation, one being prompted by tariffs and the other by failed polices relating to energy security. One has an economy that is growing as a result of consumers continuing to spend despite a volatile political and economic environment, whilst the other has a pedestrian growth rate, propped up by increasing Government spending.

Of course, no prizes for guessing that the UK is the one struggling, although I by no means diminish the problems the US faces, only their central bank is not the one turning the screw on its citizens out of dogma.

The BoE vote split according to their August 7th meeting saw the MPC taking an unprecedented second vote following a tie in the first (4 to cut, 4 to hold, 1 to raise). Mercifully, 5 did vote to cut rates by 0.25% come the second vote, but the narrow nature in which it passed was still a significant shock, with the Bank leaning far more neutral regarding policy than expected. If the Bank of England has not learned that you cannot stop inflation originating from a supply side energy shock by raising interest rates, we really are in big trouble.

Across the pond, US officials are gearing up to cut rates come September, owing to concerns regarding the labour market, a labour market which saw a 0.1% increase in unemployment for only the 2nd time this year at last print.

Yet the Bank of England is determined to hold rates steady in September, even as rumours of a tax raiding budget, fleecing the already hard pressed public to the tune of £50bln, begin their rounds ahead of the Chancellor’s Autumn statement.

Sterling may have received a short term boost from this most recent surprise, especially given just how tight the decision was and the subsequent rise in inflation. But, with the Government getting ready to unleash more fiscal punishment on the public come the budget, British consumers are squeezed between a rock and a hard place.

USD on the other hand, which has taken a beating all throughout this year, could see a brighter long term picture as the Fed lowers rates. That should spur growth, whilst at the same time, the UK will have choked further under the yolk of 4.00% interest rates. This sets up a longer term bullish USD outlook, especially as Trump’s more expansionary fiscal policy filters into the economy and triggers higher spending.

Regardless, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to see reasons that Sterling may rally.

![Week ahead – Markets brace for central bank barrage amid heightened uncertainty [Video]](https://www.europesays.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Federal-Reserve-Building_1_Large.png)