Donald Trump’s January 2025 return to the White House kicked off a new phase in Japan-US ties. In the second part of our interview with the sociologist and bilateral relationship expert Yoshimi Shun’ya, he examines the modern history of ties between the nations and looks at prospects for what comes next.

(For the first part of Yoshimi Shun’ya’s analysis, see “Trump’s Return Puts Japan-US Partnership to the Test.”)

Japanese Letters to MacArthur

Japan’s unconditional surrender 80 years ago marked the greatest turning point in the country’s relationship with the United States. Japan would lose its independence and endure over six years as an occupied nation. The focal point of this occupation was GHQ, the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers led by US General Douglas MacArthur.

The sociologist Yoshimi Shun’ya has discussed various episodes from the Occupation period in his writings. One of these was public correspondence with GHQ, in the form of the approximately 440,000 letters sent by Japanese writers to General MacArthur that were detailed in Sodei Rinjirō’s 2001 Dear General MacArthur.

What is surprising is that many of the preserved letters expressed goodwill toward General MacArthur and the United States. They expressed acceptance of American rule “for the future happiness of all Japanese people and their descendants” and a desire to entrust in the United States the responsibility for rebuilding Japan based on American guidance. Some letters even proposed a union of Japan and the United States.

Just a few years before this, most Japanese had despised the “barbaric Americans and British”—those left on the home islands, in particular, having experienced their major cities reduced to rubble by air raids, including the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“Behold the tyranny and inhumanity! The demonic Americans and British finally reveal their true nature.” A headline from a 1942 issue of Dōmei shashin tokuhō, an illustrated bulletin on Japan’s wartime advances. (© Kyōdō)

How did such a rapid about-face occur?

Yoshimi believes this change is not so hard to understand if we look at Japanese history. He argues that “the basic tendency of the Japanese since the Meiji era [1868–1902] has been one of maintaining a sense of superiority vis-a-vis mainland Asian nations by positioning themselves closer to Western civilization, as embodied by the United States.”

While China was counted among the victorious nations of World War II, Yoshimi notes that if the commander of the occupation had been Chinese instead of American, it is unlikely the general population would have been so amenable. In essence, postwar Japanese reverence of MacArthur and alignment with the United States enabled Japan to “maintain the same superiority complex versus Asia as they had maintained before World War II.” In Yoshimi’s estimation, this is why, despite the strong opposition seen in the lead-up to the 1960 US-Japan Security Treaty, the Japanese in the end shifted to a pro-American stance and accepted the new form of the relationship.

Approximately 200,000 people lined the streets to bid farewell to Douglas MacArthur following his six years in Japan. (© Kyōdō)

The “Black Ships” and America’s Westward Expansion

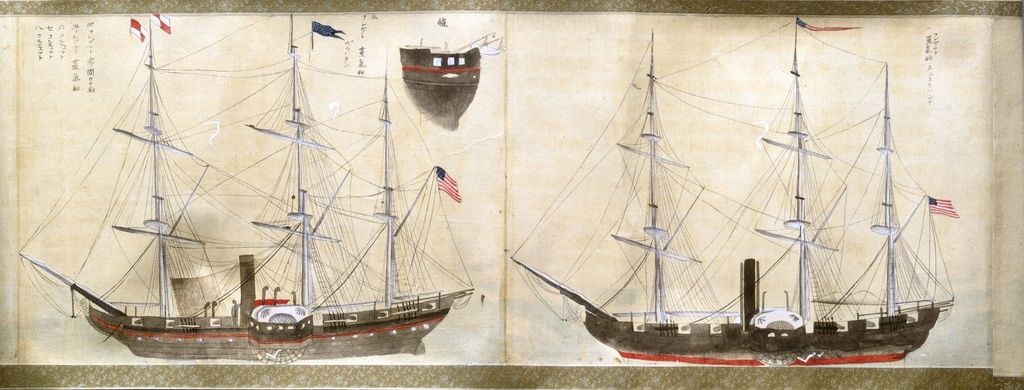

In Yoshimi’s telling, the origin of this mentality can be traced back to the arrival of US Commodore Matthew Perry’s “Black Ships” in 1853. Faced with the military might symbolized by Perry’s fleet of state-of-the-art steamships, the Edo shogunate was forced to abandon its long-standing isolationist policy and begin opening Japan to the world. Due to the ensuing domestic social and political turmoil, however, the Edo government would eventually fall. Yoshimi outlines how the 1868 Meiji Restoration not only brought a new style of government to Japan but also resulted in a major shift in the Japanese mindset. This shift disrupted the approximately 1,500-year-old perception of China, the neighboring continental power, as the prime reference point for Japan—a view exemplified by the diplomatic missions sent by Japanese rulers to Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) China.

A contemporary print shows two of Perry’s “black ships.” (© Kyōdō)

Professor Yoshimi continues: “Before Perry’s arrival, Japan’s rulers were always conscious of maintaining a certain distance from China. While they wanted to emulate certain aspects of Imperial China’s advanced civilization, they were also wary of being absorbed into the Chinese empire.” However, the black ships demonstrated to Japanese leaders that another country existed with significant power and an even more advanced civilization to Japan’s east. This presented an opportunity for Japan to use relations with the United States as leverage and even to gain an advantage over China.

Looking at the arrival of Perry’s mission from the American perspective, a completely different picture emerges, however.

As is well known, the 13 colonies of the eastern United States gained independence from Britain in 1776, and the new government gradually expanded its territory westward while seizing the lands of indigenous peoples. By 1848, American settlers had annexed the territories on the continent’s west coast and absorbed them into the United States. According to Yoshimi, “Americans justified the mass slaughter of indigenous peoples, the seizure of their lands, and the colonization of Pacific islands” based on the mandate of “Manifest Destiny.”

The notion of “Manifest Destiny” would soon push the United States into the Pacific Ocean, where it would become an imperial power itself. While the Japanese eventually came to see the arrival of the black ships and the opening up of Japan as an opportunity to modernize the nation, Yoshimi explains how Perry conducted thorough surveys and measurements of important geographic features throughout Japan, “as if he was anticipating the military conflicts in future generations.”

Thus, the Perry expedition for Americans was in essence the assertion of hegemony. It was but one event connected beneath the surface to the American westward expansion, eventually resulting in the annexation of Hawaii, other Pacific Islands, and the Philippines.

Yoshimi notes how the presence of MacArthur himself connects the events of the nineteenth century to America’s postwar occupation: “The United States would go on to win the war against Spain in 1898 and took possession of the Philippines. At that time, Arthur MacArthur Jr., the father of General MacArthur, became the military governor-general of the Philippines and brutally suppressed the local independence movement. General MacArthur, who admired his father, looked to him as a source of hints on the governing of occupied Japan. In this way, through the MacArthur family, the chain of events from the annexation of the Philippines to the occupation of Japan can be seen as a straight line.

Japan’s Superiority Complex Maintained

At the core of the US-Japan relationship sat these differing agendas that would eventually escalate into total warfare with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. The result was widespread killing and mass destruction. In American wartime publications, Japanese people were often depicted as “monkeys.” In Japan, Americans were frequently portrayed as demonic and devilish monsters.

For Yoshimi, “the underlying reason why Japanese were portrayed as ‘monkeys’ was due to racialized notions of social evolution. Americans believed that white, Western society was the pinnacle of civilization, and that developing countries in Asia—including Japan—were at an earlier stage of primate evolution, akin to monkeys.”

The result was the dehumanization of the enemy in a way that “allowed the United States to coldly analyze the structure of Japanese society and its urban areas, and based on this data, carry out indiscriminate mass killings through air raids on the mainland.” Japan, however, purportedly lacked the emotionless, scientific mindset and data needed to confront the United States directly, and mostly “viewed the United States as an insatiable, demonic monster.”

Professor Yoshimi Shun’ya. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

Therefore, as Japan and its citizenry willingly submitted and supported the postwar occupation, Yoshimi argues that it essentially meant that Japan chose to position itself below the United States in the racial hierarchy—although by working with the United States, it would allow Japan to maintain its own sense of “racial” superiority over other Asian countries.

Consuming America: The Symbol of Tokyo Disneyland

With the onset of the Cold War, Japan began to enjoy economic prosperity within the framework the US-Japan Security Treaty. American culture was embraced and consumed throughout Japanese society as symbols of affluence. Yoshimi explains how this suited American interests well:

“The military front lines of the Cold War in Asia were the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, Vietnam, and the Philippines. To support this military front, an economic and industrial base was needed close by. That was Japan. The United States provided Japan with technology and funds to revive its economy and to promote the development of independent industries so that Japan could play this critical role. From Japan’s perspective, it was an opportunity to expand its Asian markets and become prosperous without taking on military risks. Many Japanese gladly embraced this opportunity. The US-Japan security framework tied together the United States and Japan militarily, while also enabling progressive integration of economic and cultural life.

Tokyo Disneyland celebrated 40 years in business in 2023, and remains crowded to this day. (© Jiji)

Yoshimi cites Tokyo Disneyland, which opened in 1983, as one such symbol of Japan’s integration with the United States and as a focus of Japanese postwar consumption of American culture.

“The ‘themed lands’ at Tokyo Disney promote a very American worldview. ‘Western Land’ is modeled after the Wild West era of pioneering expansion when frontier land was seized, and indigenous peoples were driven out. In ‘Adventure Land,’ visitors can explore jungles and tropical islands, essentially tracing the path of the westward expansion of the United States into the Pacific and beyond. Commodore Perry’s expedition and the Pacific War are therefore extensions of this history. However, many Japanese enjoy these attractions without being aware of these undertones. Japanese can essentially consume a fantasy of being integrated with the United States. But it is, ultimately, a fantasy.”

The Importance of the Maritime

However, this situation may not continue indefinitely. A major catalyst for change could be the re-election of US President Donald Trump. As mentioned in the first article in this series, if Japanese sentiment toward the United States deteriorates due to the Trump administration’s coercive policies, it could lead to a fatal rift in the bilateral relationship.

However, looking to Japan’s west, there is China, which has become an economic powerhouse in its own right and is rapidly increasing its military strength. Threats from North Korea and Russia also cannot be ignored. What path should Japan’s diplomacy pursue to navigate these tensions?

Yoshimi reflects on the changing nature of the global order over the last century. He describes how the twentieth century can be viewed as an era of “centripetal force” centered on huge empires such as the United States and the Soviet Union with massive gravitational pull. This underpinned the progression of globalization. According to Yoshimi, in the contemporary era, “globalization has reached its limits, we are now in an era where ‘centrifugal forces’ are dominant.” The result is that pressures will likely push countries apart, meaning that global order is less likely to center on one or two core powers.

In this context, Yoshimi believes that Japan’s relations with countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, and Southeast Asian nations will become even more important than ever.

“The waters of the Western Pacific are home to the Japanese archipelago, the Philippines, Indonesia, and thousands of other islands and coastal countries, each with a rich cultural heritage. There may be an option for the countries in this littoral and archipelagic region to connect with one another and carve out a distinct diplomatic approach that maintains distance from both the United States and China.”

Indeed, Japan may have already reached a point where it can no longer afford to merely follow the lead of the Trump administration or the United States in general. Has the time come to begin exploring “new paths” for Japanese diplomacy?

(Originally published in Japanese on August 13, 2025. Text by Koizumi Kōhei and Power News’s Igarashi Kyōji. Banner photo: Yoshimi Shun’ya at the Kokugakuin University Tama Plaza Campus. © Yokozeki Kazuhiro.)