This article contains spoilers for all three versions of The War of the Roses.

In a New York Times review of Warren Adler’s 1981 novel The War of the Roses, novelist Avery Corman argued that the book’s main characters, Jonathan and Barbara Rose, are so awful they are—to put it in modern parlance—unrelatable. “Why should we care about the Roses? Their actions are so special, they are both so cruel to each other, to their children, we start to back away from them,” Corman, himself the author of Kramer vs. Kramer, the 1977 novel about another divorcing couple, wrote. “The War of the Roses, which began with universals, turns into a novel only about the Roses, about two driven, immature people.”

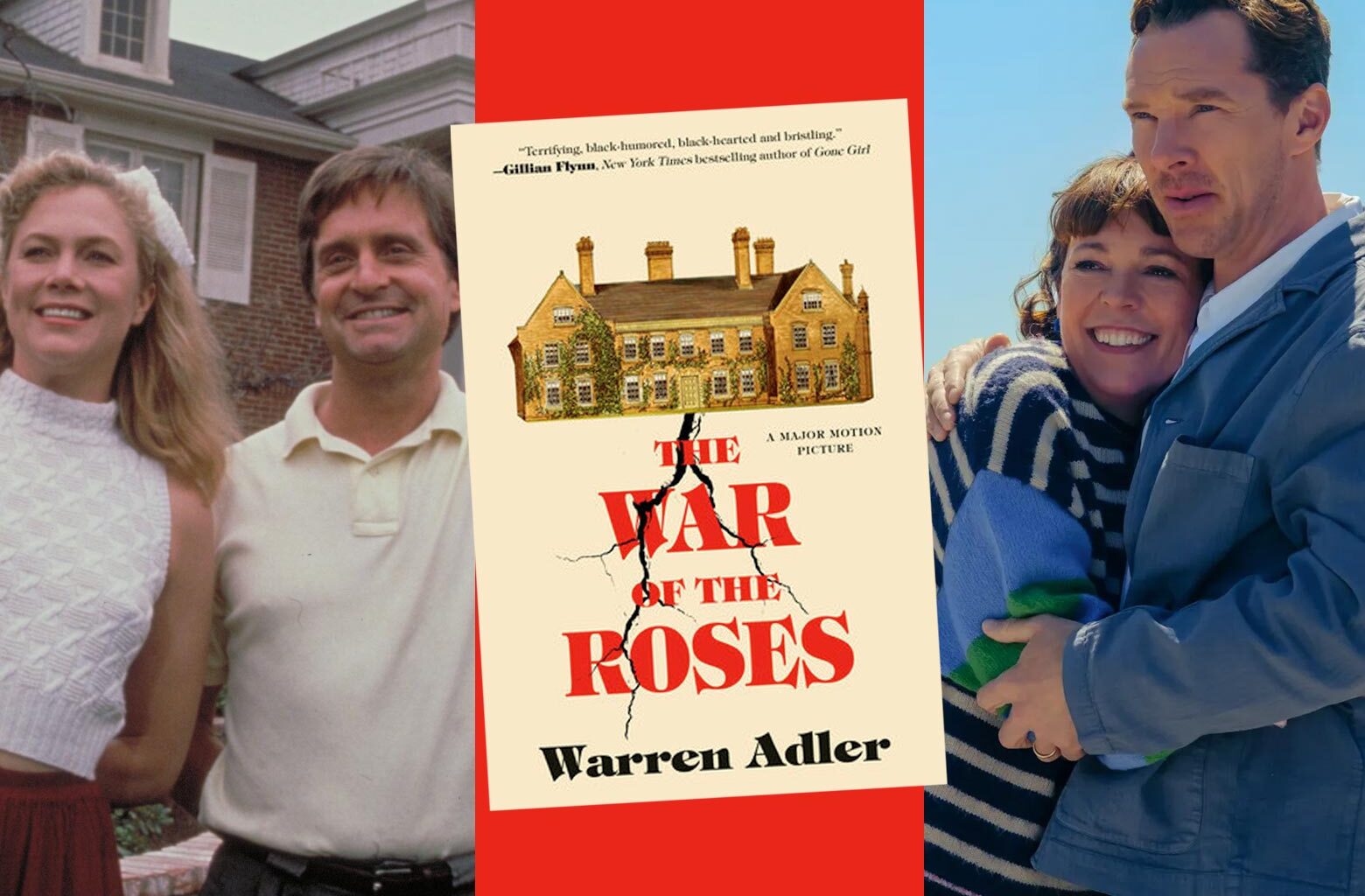

It’s true—The War of the Roses, which has now been reissued on the occasion of Jay Roach’s new movie adaptation, The Roses, is never sad, never sweet. It’s a domestic horror show, channeling the rancorous spirit of the 1970s, when second-wave feminism’s critiques of heterosexual partnership sparked epic culture wars over marriage. Most other reviews of the book embraced the novel’s spirit, and Danny DeVito’s 1989 film adaptation, starring Michael Douglas and Kathleen Turner, offered almost as much claustrophobia and cruelty as the novel. Audiences at the time seemed to like that—DeVito’s film grossed $178 million stateside.

The 2025 adaptation, opening this weekend and apparently trying for something a bit more palatable, adjusts the Roses back toward the universal. In casting Benedict Cumberbatch and Olivia Colman as the divorcing couple, Roach has made the whole thing much easier to watch. Almost too easy: The two have a palpable chemistry that makes every little fight seem as if it will surely be resolved in the next scene. (And often it is.)

The Rose marriage’s new trajectory is fundamentally different—an adjustment that nods to changing times but saps the conflict of its force, making it confusing to parse. In the Adler novel, and the DeVito adaptation, Barbara is a stay-at-home mom who supported Jonathan while he became a highly paid lawyer. Then, in the year their twins are applying to college, she starts to do some catering, which gives her that bit of self-confidence she needs to realize that her husband truly is an unctuous prick (picture, well, Michael Douglas, fresh off his Oscar for playing Wall Street’s Gordon Gekko—that was good casting) and she could leave him if she wanted.

In the 2025 movie, Theo and Ivy are both well-paid creatives—he’s an architect, and she’s a cook—who are supportive of each other’s vision and drive. She takes time off when the kids are little, then they crisscross, as his career craters and hers takes off. They bicker over who will step back from a job to handle the family, but that problem is fundamentally solved by the early departure of their 13-year-old twins to boarding school. The story becomes a more modern one, but it loses the easily parsable conflict between breadwinner and homemaker that gave The War of the Roses its engine.

The midcentury names Barbara and Jonathan are gone, in favor of Theo and Ivy; these two could just insert an ampersand and start a neutral-colors baby-clothes brand. The new Roses are British expats, living in California and moving from one nice house to another, nicer one, rather than two Americans who are working-class (Barbara) and upper-middle-class (Jonathan), ascending together to a beautiful home in Washington’s exclusive Kalorama neighborhood, full of meticulously selected antiques. The little gestures toward class conflict in Adler’s novel and DeVito’s adaptation—Jonathan corrects Barbara’s pronunciation in public and, in a genius addition to the story by DeVito’s movie, censures her for feeding the children too much sugar—get flattened out, bringing the Roses closer together, making their conflicts look more like a product of the narcissism of small differences.

Ivy and Theo fight about taste, just a little. Theo doesn’t like Ivy’s idea to put an antique stove into his much more modern design, and Ivy bristles at the expensive Irish moss Theo orders for the new house’s roof, because it’s got such a particular color green. And Ivy is the one who wants to feed the kids dessert, while Theo, when he takes over their upbringing, turns them into little athletes, fixated on rep counts and blood-sugar regulation. But these feel like minor vestiges of the original versions of the story, which was as much about the toxicity of upward mobility as about love, marriage, and divorce.

The script of The Roses, written by Tony McNamara, takes the part of the novel where the couple destroys their perfect house, committing various assaults on each other in the process—a highly imaginative tale of destruction that comprises most of the book’s plot—and stuffs it all into the climactic final 15 minutes of the film. In the theater, I kept looking down at my watch, wondering when the smashing was going to begin.

The novel’s Roses kill each other’s pets. (DeVito bravely included a scene in his adaptation in which Barbara feeds her husband pâté that’s made of meat from his dog. “Woof,” Kathleen Turner says, flatly, at the reveal.) Jonathan has sex with the au pair; Barbara locks him in the sauna and turns it up. Jonathan empties out Barbara’s Valium capsules and puts Dexedrine in them; Barbara doses Jonathan’s orange juice with LSD. Jonathan ruins a dinner party Barbara is catering by booby-trapping the kitchen.

Adler goes on and on, creating a mood in the house that’s so suffocating and macabre that, by the end you’re absolutely dying to get out. Home Alone wishes. And The Roses definitely wishes. Colman and Cumberbatch are game, crashing a chandelier, ruining one another’s careers via A.I.-generated video, and locking each other in a room while polka music plays, but zero pets are harmed—a little thing, maybe, but a barometer for just how unlikable this movie is willing to let its characters become (not very).

Corman dinged the novel for focusing the Roses’ conflicts on stuff. “For the Roses … the house, the possessions, the antiques become even more important than their children,” he wrote. “The question for Jonathan and Barbara Rose is who will get custody of the things?” This reviewer was a man who wrote a novel about a battle over child custody, one that was probably the most iconic popular novel about divorce immediately preceding The War of the Roses’ publication, so it makes some sense he’d get stuck on this.

Haley Swenson

American Women Aren’t Too Happy. I’m Just Not Convinced Marriage Is the Answer.

Read More

But the whole point of putting the original Roses in that Kalorama mansion, full of antiques that they start accumulating the very day they meet, was to poke at this kind of person, who thinks “only things increase in value,” as Jonathan says to Barbara at one point. “People diminish.”

The antiques that the novel’s Roses purchase—Staffordshire figurines, sleigh beds, Tiffany lamps—are not just valuable in terms of money. They are Jonathan’s bids toward a type of immortality—Jonathan, burrowing into the upper class. That’s why Barbara can’t let him have them. She hates his pathetic social climbing and can’t abide the idea that he would get away with that unscathed. That’s why the scene in DeVito’s adaptation in which Turner smashes his Staffordshires is so satisfying.

Antiques like the ones that stuffed the Roses’ original house have been losing value in the real world since about the turn of the 21st century, so an update to The War of the Roses has to look different. The new movie’s cliff house, filled with stylish modern furniture and sporting a whole-house digital assistant the Roses (of course) nickname “Hal,” symbolizes a type of California creative-class wealth that bends toward the artisanal and organic. These Roses are not scheming to get into the upper class. They’re people who spend tremendous amounts of money to see the ocean from every room, but they seem to be doing it only to help their own careers. This is a different kind of American rich person, and one that is also interesting to satirize. But The Roses doesn’t have the meanness required to twist the knife.

Netflix’s Star-Studded New Movie Adapts a Beloved Mystery Novel. It Butchers It.

Most TV Shows Get This Major Plot Point Totally Wrong. This New Netflix Series Nailed It.

What Sabrina Carpenter’s Critics Misunderstand About Her

We Officially Have the Most Entertaining Celebrity Trial of the Year

The changes to the ending show how defanged this story has been by these adjustments to modernity. Adler’s couple dies after weeks of battle, locked in their boarded-up house, sweating, sick, poisoned, trapped with the debris of their storybook marriage. DeVito’s adaptation streamlines their descent but still leaves the couple dead in their entry hall, after falling from their chandelier. The husband wordlessly seeks forgiveness, creeping a hand toward his wife, and in her last act, Barbara rejects it. In The Roses, instead, the couple has reached a cuddly rapprochement, until they ask Hal to light a fire, not knowing that ever since Theo bashed up Ivy’s stove during the fight, gas has been leaking into the house. The screen turns totally white, and the title card reappears. Rest in peace to the Roses, and that gorgeous house.

Adler, who died in 2019 at age 91, was married for 67 years—by all accounts, happily. He got the idea for The War of the Roses from observing a divorcing couple in his social circle. This new film seems unlikely to capture the marital zeitgeist the way the novel did. Maybe the phenomenon of easily available divorce was all just too new, at the time. Since then, it’s been drained of its bite by the same dispersal of culture that’s made everything that was once monocultural seem less important. Now we have Liars, Marriage Story, online discourse about leaked Steven Crowder home surveillance videos, our very own divorce column—lots of ways to talk about why couples split. Do we need The Roses? Sadly, I don’t think so.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.