The theoretical nexus between conflict and poverty is situated within relative deprivation, grievance, and greed theories. Relative deprivation, grievance, and greed theories were selected because they collectively capture the psychological, structural, and economic motivations behind conflict, provide robust frameworks for understanding inequality-driven unrest in SSA, and align with empirical evidence highlighting how perceived injustice, marginalisation, and resource competition fuel violence, which leads to poverty. According to the relative deprivation theory, conflicts and social unrest can arise when groups or individuals perceive a discrepancy between their expected and actual material or social conditions (Smith et al. 2020). The theory explains social dynamics regarding groups’ access to power and the subjugation of disadvantaged members of society (Irobi, 2005). Gurr (1970) and Draman (2003) argue that conflicts arise when groups or individuals feel they are not receiving their fair share of commonly owned socioeconomic resources or opportunities relative to others. This can lead to frustration and aggression, potentially manifesting in violent conflict. This is particularly the case in Africa, where weak governance structures, unequal access to social amenities and economic resources, political/ethnic marginalisation, and discrimination create disparities in opportunities among different social groups (Alayande et al. 2022; Azoro et al. 2021; Draman 2003; Edokat and Njong 2019; Ikejiaku 2012; Ndulo 2021). These conditions foster inequality in resources and access to opportunities between the different social groups, potentially leading to heightened tensions and conflict. This perspective is supported by studies highlighting how unequal resource distribution and poor governance can exacerbate feelings of injustice and social unrest (Smith et al. 2012; Gurr 1970). Therefore, understanding relative deprivation is crucial for addressing the root causes of conflict and implementing effective governance and resource distribution policies that benefit all social groups in a country or community. However, Smith et al. (2012) highlight that the theory’s predictive power is often weak and inconsistent across different contexts, complicating efforts to draw clear conclusions from empirical studies.

Grievance theory suggests that conflicts can be driven by ethnic marginalisation, political repression, and economic inequality. These conditions form the basis for depriving communities and individuals of demanding their share of the resources or restructuring the political and economic frameworks. Such grievances and demands by the deprived groups could trigger conflict. This theory is often applied to explain civil conflicts and insurgencies, where internal divisions and unfair treatment by governing bodies or dominant groups play a central role. Poverty interlinks with both motives but is particularly relevant to grievances, where impoverished conditions can exacerbate societal frustrations and the perceived injustices that translate into violent conflict. Thompson and Lee (2020) argue that in SSA, while access to resources may attract conflict actors due to greed, the underlying grievances about who benefits often ignite and sustain conflicts. This is why when groups perceive a gap between their expected and actual socioeconomic conditions, particularly when compared to other groups, they may act violently to gain access, leading to conflict (Walters and Nguyen 2019).

Greed theory argues that conflict is used to gain control of resources. Greed theory is rooted in the idea that the opportunity for economic gain is a significant driver of conflict. It argues that the availability of lootable resources and the feasibility of sustaining rebel groups through such wealth trigger the outbreak and sustenance of violent conflicts. This theory shifts focus from socio-political or cultural factors to economic incentives as primary motivators for conflict. This is why Collier and Hoeffler (2004) argue that dependency on primary commodity exports and the availability of finance through diasporas increase the risk of conflict. Therefore, it is unsurprising that resource-rich African countries are embroiled in conflict (Martinez and Goldberg 2018).

In the SSA context, the interaction of relative deprivation, grievance, and greed theories offers a robust multidimensional framework for understanding the poverty–conflict nexus. The relative deprivation theory is supported by findings from Fagbemi and Fajingbesi (2022), who show that unfavourable economic conditions and perceived inequality are key drivers of political instability in SSA, especially in large populations. Tollefsen (2020) adds to this by revealing that poverty exacerbates violence in regions with weak institutions and collective grievances, emphasising how marginalised groups compare themselves with more privileged ones, leading to social tension and unrest. Similarly, Nogales and Oldiges (2024) highlight how violence disrupts poverty reduction efforts, even in relatively well-off areas—suggesting that perceived inequality and not absolute poverty alone may drive conflict. This aligns with Braithwaite et al. (2014), who find a direct causal relationship between poverty and conflict using instrumental variable regression, reinforcing the emotional and psychological roots of discontent emphasised by relative deprivation theory.

Grievance and greed theories further extend the explanatory power of this framework. Grievance theory, which focuses on marginalisation and political repression, is evident in the findings of Tollefsen (2020) and Ikejiaku (2012), who point to institutional failures and social injustice as triggers for violent mobilisation. Studies on Nigeria’s Boko Haram insurgency (Odozi and Oyelere 2019; Adelaja and George 2019) and Ethiopia’s conflicts (Abay et al. 2023) show that poverty worsens grievances, pushing marginalised groups toward resistance. Meanwhile, greed theory, which centres on economic incentives for violence, is reinforced by Hegre et al. (2009), who find that conflict frequently occurs in wealthier areas, suggesting that access to resources and the feasibility of sustaining rebellion are key motivators. Nogales and Oldiges (2024) also highlight this paradox by showing that conflict often disrupts development in areas that had been making poverty reduction gains and this is perhaps because few individuals often seek to control economic resources. This is evident in resource-rich states like the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan (Collier and Hoeffler 2004). This exploitation perpetuates a self-reinforcing cycle: while poverty may initially trigger conflict (Ikejiaku 2012; Braithwaite et al. 2014), the resulting violence further entrenches deprivation by destabilising livelihoods and eroding governance capacity. Consequently, poverty in SSA is not a singular or isolated cause of conflict—it interacts with perceptions of injustice, historical exclusion, and the strategic ambitions of actors to control resources. Thus, a nuanced understanding incorporating all three theories is critical for designing effective, conflict-sensitive poverty reduction policies and regional governance reforms.

Causal pathways between poverty and conflict in SSA

There is a significant divergence of opinion regarding the precise correlation between poverty and conflict. One perspective posits that poverty is the root cause of conflict, whereas the other contends that only the opposite holds (Draman 2003). Undeniably, the connection between poverty and conflict is ambiguous. However, we contend in this article that poverty in SSA is both a catalyst and an outcome of violent conflict.

Poverty as a driver of conflict

The causal link between poverty and conflict has been a prominent research subject in comprehending Africa’s socio-political dynamics. Several researchers have investigated the causal relationship between poverty and conflict, exploring the complex mechanisms by which impoverished circumstances can result in violence and instability. This research offers vital insights into the intricate linkages between poverty and conflict. We do this by providing evidence indicating that poverty can contribute to violence through direct and indirect mechanism. This section provides an overview of the relevant studies (Table 1) examining poverty as a cause of conflict in SSA settings. It emphasises the techniques, findings, and consequences of these studies.

The discussion commences with Nogales and Oldiges (2024), who examined the correlation between multidimensional poverty trends and conflict patterns in Nigeria from 2008 to 2018. Their broad conceptualisation of poverty encompasses both financial and non-financial deprivation. Specifically, they analyse how poverty levels vary across regions experiencing active conflict, those recovering from conflict, and peaceful areas. Based on spatial regression, their findings indicate that conflict does not always erupt in the poorest regions but can also occur in comparatively wealthier areas. Furthermore, although the MPI declined between 2008 and 2013, violence significantly impeded or reversed progress in poverty alleviation Table 2.

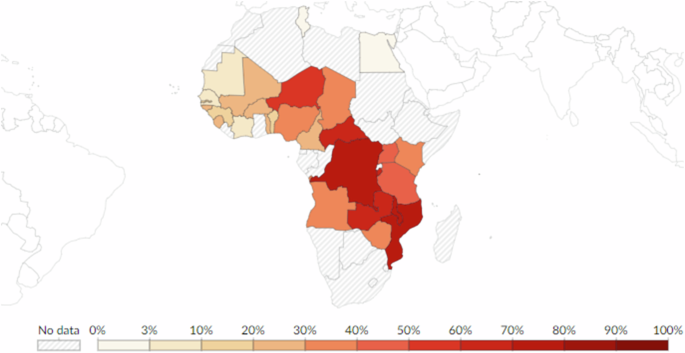

Similarly, Tollefsen (2020) uses georeferenced Afrobarometer data from 4008 subnational districts across 35 SSA countries to investigate the poverty-conflict nexus. His findings point to an inverse relationship, whereby poverty exacerbates violence, particularly in regions with weak local institutions and pronounced collective grievances. Extending this inquiry, Fagbemi and Fajingbesi (2022) assess how adverse economic conditions contribute to violence across 25 SSA countries between 2005 and 2019. Drawing on frustration-aggression and relative deprivation theories, their analysis reveals that countries with larger populations are more susceptible to political instability. Interestingly, they also find that foreign direct investment has no consistent effect—positive or negative—on political stability.

In contrast, Braithwaite et al. (2014) adopt an instrumental variables probit regression to establish a direct causal relationship between poverty and conflict. Their findings reinforce the assertion that poverty significantly drives conflict. Meanwhile, Ikejiaku (2012) presents a reciprocal view, arguing that while conflict exacerbates poverty, poverty can catalyse it. This perspective is further complicated by Hegre et al. (2009), who utilise ACLED and local socioeconomic data from Liberia to reveal that conflict incidents were more common in wealthier regions—suggesting that the drivers of conflict go beyond poverty alone.

Taken together, the findings of Tollefsen (2020) and Braithwaite et al. (2014) confirm indirect and direct causal relationships between poverty and conflict, although their methodologies and interpretations differ. Ikejiaku (2012) adds depth to this discourse by emphasising the bidirectional nature of the relationship, while Hegre et al. (2009) challenge the conventional wisdom by demonstrating that affluent areas are not immune to conflict. This implies that, though influential, poverty cannot be viewed in isolation from other contextual and institutional factors.

In summary, the poverty-conflict relationship in Africa is multifaceted and influenced by institutional strength, socio-political grievances, and regional disparities. The findings highlight the importance of moving beyond simplistic narratives that associate violence exclusively with impoverished settings. Instead, they call for nuanced policy responses tackling inequality, governance weaknesses, and social exclusion to promote sustainable regional peace and development.

Conflict as a driver of poverty

Understanding how conflict drives poverty is crucial to developing efficient solutions. Several studies have attempted to quantify and record the impact of conflict on different socioeconomic indicators, emphasising the substantial burden that violence may impose on communities. Here, we explore how conflict causes poverty.

The discussion begins with Gebrihet et al. (2025), who examined the impact of prolonged armed conflict on urban food security in Tigray, Ethiopia. The study reported alarmingly high levels of food insecurity, with only a small portion of households classified as food insecure and 39% experiencing hunger in the post-conflict period. Poor food consumption was prevalent, and stress-level coping strategies were the most widely adopted by affected households. Similarly, Abay et al. (2023) assessed the effects of active conflict on welfare and livelihoods in Ethiopia, finding that conflict exacerbated food insecurity by 37 percentage points. Notably, each additional conflict increased the likelihood of food insecurity by one percentage point, mainly due to disruptions in food supply networks and non-farm livelihood activities, though farming operations showed relative resilience. Relatedly, Shettima et al. (2023) examined the conflict–energy poverty nexus in SSA and found that conflict-related fatalities consistently affected electricity consumption, production, and access levels across all panel data models. Earlier, Okunlola and Okafor (2022) conducted a broader analysis across Africa from 1980 to 2015, concluding that internal conflicts—more than interstate ones—substantially worsen poverty and reduce living standards. In Nigeria, Odozi and Oyelere (2019) examined the effects of the Boko Haram insurgency and Fulani herder-farmer conflicts, revealing that prolonged exposure to violence significantly intensified the extent and severity of poverty.

Aside from that, Adelaja and George (2019) examined the consequences of the Boko Haram insurgency on agriculture in Nigeria. By integrating nationwide agricultural panel data with conflict data, their study revealed that the intensity of Boko Haram attacks significantly reduced agricultural productivity and efficiency, particularly affecting the cultivation of staple crops and agricultural wages. Building on this, George et al. (2020) expanded the scope by investigating the broader food security implications of the insurgency. The findings showed that increased conflict intensity directly contributed to food insecurity, mainly through agricultural inputs and income source disruptions.

Similarly, Abay et al. (2023) assessed the effects of recent large-scale conflict on household food security in Ethiopia. Their results highlighted a marked increase in food insecurity and significant disruptions to livelihood activities, further underscoring the adverse socioeconomic consequences of conflict. Complementing these insights, Mercier et al. (2020) provided a longitudinal analysis of the Burundi Civil Conflict, revealing that households exposed to violence faced a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing food poverty, emphasising the enduring nature of conflict-induced poverty.

Beyond food security, other scholars explored the broader human development consequences of conflict. For instance, Minoiu and Shemyakina (2012) assessed the civil strife in Côte d’Ivoire between 2002 and 2007 and found that children in conflict-affected areas suffered from substantial health impairments due to the economic and psychosocial stresses associated with violence. Furthermore, Weldeegzie (2017) and Bertoni et al. (2019) explored educational outcomes. Weldeegzie, in examining the Ethiopia-Eritrea border conflict, identified significant adverse effects on child health and schooling. Similarly, Bertoni et al. found that the Boko Haram conflict in Nigeria led to sharp declines in school enrollment and educational attainment, revealing long-term setbacks in human capital development.

The works of Odozi and Oyelere (2019) and Adelaja and George (2019) reinforced the narrative that conflict exacerbates poverty, particularly by diminishing agricultural outputs and worsening overall economic well-being in Nigeria. George et al. (2020) added further nuance by linking these effects directly to food insecurity, aligning with the earlier findings of Odozi and Oyelere. Meanwhile, Abay et al. (2023) and Mercier et al. (2020) offered evidence from Ethiopia and Burundi highlighting similar conflict-induced poverty and food insecurity trends.

Moreover, broader comparative analyses help situate these findings within a regional context. For example, Okunlola and Okafor (2022) and Minoiu and Shemyakina (2012) differentiated the impacts of internal versus interstate conflicts across Africa and underscored that internal conflicts tend to have more severe implications for poverty and human development. While Minoiu and Shemyakina focused on child health in Côte d’Ivoire, Weldeegzie (2017) and Bertoni et al. (2019) revealed how conflict interrupts education, thereby compromising long-term poverty alleviation efforts.

The overarching theme emerging from these studies is that conflict—particularly internal conflict—has far-reaching and multifaceted negative impacts on socio-economic development in SSA. As Luckham et al. (2001) elaborate, conflict affects livelihoods at the macro, meso, and micro levels by disrupting governance, destroying infrastructure, eroding social capital, and exacerbating inequalities through asset appropriation and marginalising vulnerable groups. These cascading effects range from national economic instability to individual unemployment and food insecurity.

In conclusion, the collective evidence paints a compelling picture of the severe consequences of conflict across Africa. Whether through diminished agricultural productivity, increased food insecurity, disrupted education, or impaired health outcomes, conflict undermines individual well-being and national development trajectories. Notably, the findings reinforce that internal conflicts are especially detrimental due to their localised and enduring impacts. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive policy strategies prioritising conflict resolution, peacebuilding, institutional resilience, and inclusive development to break the cycle between poverty and conflict.

Synthesis analysis of the poverty-conflict nexus in SSA

The relationship between poverty and conflict in SSA is multifaceted and bidirectional, as illustrated by various studies. Research indicates that poverty can act as a significant driver of conflict. For example, Tollefsen (2020) and Braithwaite et al. (2014) support the hypothesis that poverty exacerbates violence, particularly in areas with weak local institutions or significant group grievances. In the case of Tollefsen, the findings highlight an indirect correlation, while Braithwaite et al. establish a causal link between poverty and conflict. Ikejiaku (2012) acknowledges the complex interplay, suggesting that conflict exacerbates poverty, though poverty can lead to conflict under certain conditions. Hegre et al. (2009) provide a nuanced view, showing that conflict events were more frequent in relatively wealthier locations, challenging the straightforward conflict poverty-conflict narrative. Thus, from the perspective of poverty as a driver of conflict, studies indicate both direct and indirect pathways through which poverty can lead to conflict, influenced by factors such as weak local institutions and significant group grievances.

Conversely, conflict significantly exacerbates poverty through reduced agricultural productivity, increased food insecurity, health setbacks, and disrupted education. Recent studies (Adelaja and George 2019; Odozi and Oyelere 2019; Okunlola and Okafor 2022) demonstrate how internal conflicts, such as those caused by Boko Haram, increase poverty rates and worsen the living standards of affected people. Specifically, the works of Abay et al. (2023) and Mercier et al. (2020) highlight the severe impact of conflict on food security and livelihood activities. Weldeegzie (2017) and Bertoni et al. (2019) documented educational setbacks due to conflict, which show significant reductions in school enrollment and completion rates. About conflict as a driver of poverty, it is evident that conflict exacerbates poverty through reduced agricultural productivity, increased food insecurity, health setbacks, and disrupted education.

The evidence underscores the complex, bidirectional nature of the poverty-conflict nexus in SSA. Poverty, particularly when coupled with weak institutions and group grievances, can escalate tensions and lead to conflict, as several studies demonstrate. Conversely, conflict further deepens poverty by disrupting agriculture, increasing food insecurity, and limiting access to education and healthcare. This cyclical relationship indicates that poverty and conflict are deeply intertwined, reinforcing one another and complicating efforts to break the cycle.

Theoretical and practical policy implication

Theoretical and practical policy implications of the poverty-conflict nexus in SSA emphasise the need for integrated approaches that simultaneously address poverty and conflict. Theoretically, the evidence underscores the bidirectional and multifaceted nature of the relationship between poverty and conflict, challenging the simplistic view that poverty alone is the root cause of conflict. Instead, factors like weak institutions, group grievances, and resource inequalities intertwine with poverty to create complex conflict dynamics. Understanding this interconnectedness helps to design interventions that target the underlying structural issues rather than focusing solely on poverty alleviation or conflict resolution in isolation.

Practically, the findings call for policy frameworks that incorporate a holistic and context-sensitive approach to development and peacebuilding. International interventions, such as foreign aid and peacekeeping missions, must align with local realities and support grassroots initiatives that empower communities. Policies should prioritise building solid and inclusive institutions and fostering economic opportunities that address local grievances. It requires shifting from top-down strategies to more participatory, community-driven models promoting sustainable development and peace.