Photo. Natalia Matiaszczyk/author’s archive

Copy link

Send email

Far from being a relic of the Cold War, South Korea’s civil defence system is a nationwide, legally mandated framework designed to protect the population from both wartime and peacetime threats. It combines post-military reserve forces, extensive network of shelters, early warning systems, and regular public drills, integrating them with modern disaster management protocols. Understanding how this system functions offers insight into how a high-threat democracy institutionalises resilience even when its citizens perceive war as a distant possibility rather than an imminent reality.

Historical Context

South Korea’s civil defence system is rooted in the unresolved legacy of the Korean War (1950–1953), which ended in an armistice rather than a peace treaty. The persistent risk of military standoff with North Korea, coupled with the threat of targeting both military and civilian infrastructure, made civilian protection one of the priorities of national authorities.

During the Cold War, civil defence in South Korea was narrowly focused on wartime scenarios, mirroring the period’s conventional threat perceptions and ideological clashes between both Korean states. The government introduced legally mandated drills, compulsory civil defence service for male citizens after military duty, and the construction of underground shelters in urban areas.

The post–Cold War era brought both adaptation and expansion. As North Korea pursued nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, South Korea’s civil defence plans evolved to address weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), while also integrating responses to non-military threats. The more common natural disasters, or attacks like the 2003 Daegu subway arson attack and the 2010 shelling of Yeonpyeong Island each exposed vulnerabilities and prompted reforms in emergency response. Today, South Korea’s civil defence is no longer confined to wartime contingencies. It operates within a broader comprehensive security framework that addresses different types threats.

Institutional Framework

Civil defence is grounded in the

Framework Act on Civil Defence

(1975), first enacted in 1975 and revised multiple times to address evolving threats. The Act mandates both the central and local governments to prepare, maintain, and operate civil defence measures in wartime, national emergencies, and disaster situations.

The Ministry of the Interior and Safety serves as the lead government body for civil defence policy. It formulates national plans, allocates resources, and coordinates with other ministries, including the Ministry of National Defence for military-linked contingencies, and the specialized agencies like National Fire Agency or River Flood Control Offices for disaster response.

Execution at the local level is the responsibility of city, county, and district governments, each maintaining a Civil Defence Office. These offices oversee shelter readiness, conduct public drills, train civil defence personnel, and liaise with police, fire, and medical services.

A distinctive feature of South Korea’s model is the Civil Defence Corps, composed mainly of male citizens aged 20 to 40 who have completed mandatory military service. These reservists serve in the Corps for several years, participating in regular training on evacuation procedures, basic rescue operations, and NBC (nuclear, biological, chemical) protection. They are

required

to complete four hours of training per year during the first and second year of service, two hours per year in the third and fourth year, and one hour annually from the fifth year of service onwards.

In peacetime, Civil Defence Corps members assist in disaster response: from flood and typhoon relief to wildfire containment. In wartime, they are tasked with guiding civilians to shelters, supporting rescue operations, securing critical infrastructure, and helping maintain public order.

Infrastructure and Resources

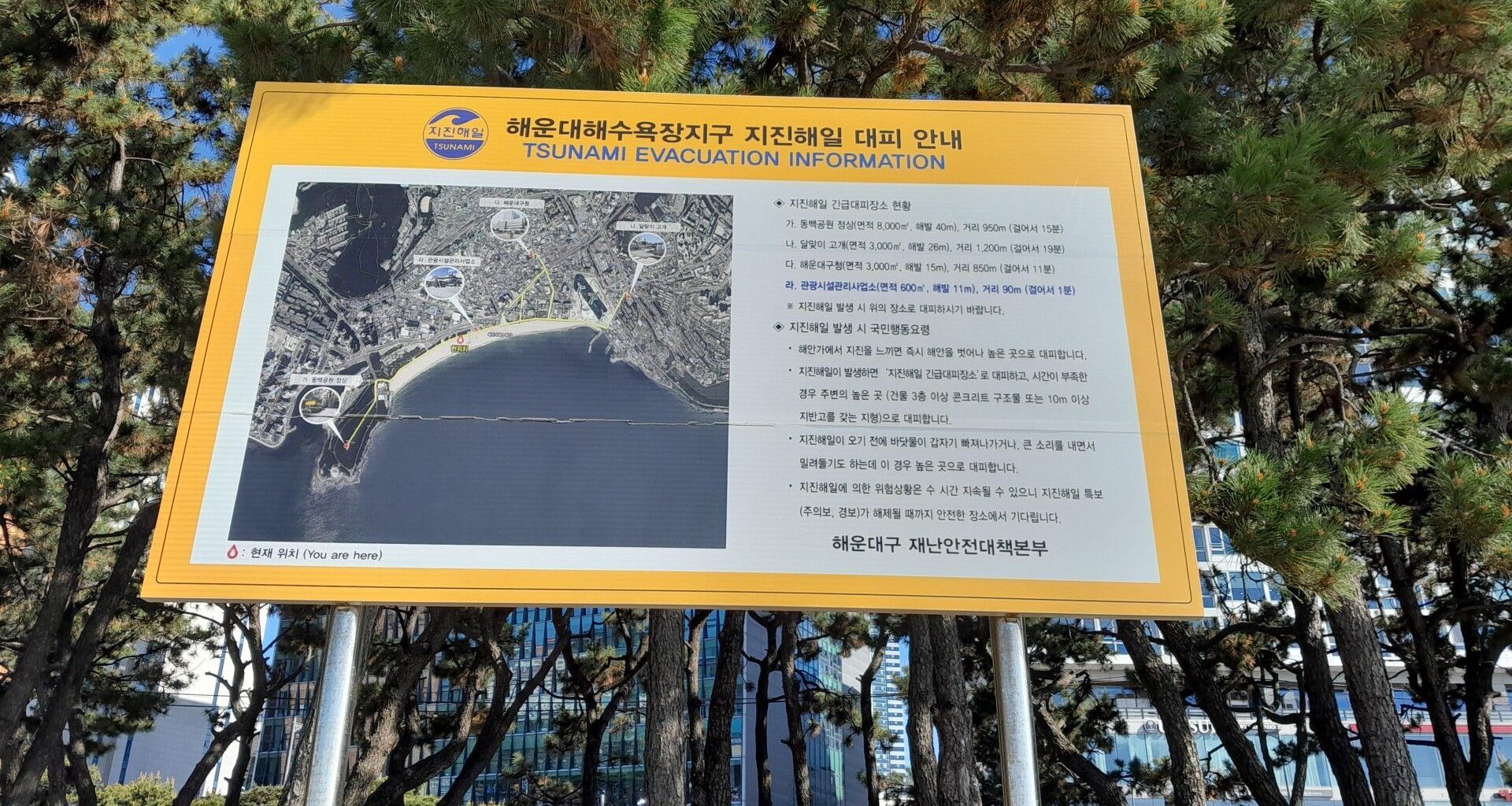

South Korea’s civil defence system relies on a nationwide network of shelters, stockpiles, and communication systems designed to provide rapid protection and sustainment during emergencies.

As of 2025, South Korea maintains

almost 17,000 designated civil defence shelters

capable of accommodating millions of people. These shelters are typically located in in subway stations, car parks, and basements of public buildings. All are marked with yellow-and-blue signage and listed in public apps. However, most of them are built as bomb shelters, and not to protect against nuclear, chemical or biological attacks. Additionally,

many shelters

lack adequate long-term supplies like food, water, and medical equipment.

There are also designated

emergency assembly areas

, which are distributed nationwide. These mostly open spaces, such as school sports fields, parks, or elevated ground, are designed to accommodate large groups safely in the aftermath of earthquakes or tsunamis, away from collapsing structures or flood zones. They are clearly signposted, and their locations are included in official safety maps. In the case of areas at risk of flooding or wildfires, local authorities prepare a list of

temporary shelters

where people can go in case of evacuation – most often these are local schools or sports centres.

A nationwide early warning system is very extensive and includes information about various types of threats. It is used by national and local authorities to provide information about threats of attacks, the risk of natural disasters, but also to provide information about extreme meteorological phenomena such as heat waves. Most common are emergency mobile messages sent simultaneously to all mobile devices in a target area. However, in the case of more serious threats, other elements are also used, like outdoor loudspeakers and sirens, or TV and radio that interrupt normal broadcasting to relay official instructions.

South Korean

national

and local governments conducts regularly civil defence drills. These drills typically involve activation of air raid sirens and public address systems, temporary halts to traffic in major cities, and guidance of pedestrians into nearby shelters or safe areas. For example,

Seoul is organizing

its own drills this Wednesday, August 20. Emergency sirens will sound at 2 p.m., and residents will be required to evacuate to the nearest shelter and remain there for 15 minutes.

Current Challenges

Despite its broad legal mandate and nationwide reach, South Korea’s civil defence system faces several challenges. While the system is quite well-suited for conventional attacks or natural disasters, adapting to new threat types such as cyberattacks on infrastructure, or combined hybrid operations, remains a work in progress. In densely populated areas, the number of shelter spaces does not fully match the resident population, particularly in scenarios requiring prolonged occupancy. Additionally, Shelter maintenance, equipment quality, and training rigor vary between local governments, reflecting differences in funding and prioritisation. The last important challenge lies in public attitudes: parts of society increasingly perceive traditional threat scenarios as outdated or merely symbolic, which has led to declining participation in civil defence drills and a tendency to

ignore alarm sirens

.

Conclusion

Civil defence in South Korea is a living component of national security. Its adaptability, expanding from air raid readiness to natural disasters resilience, demonstrates how a country can institutionalise preparedness. Although not without shortcomings, South Korea demonstrates that it is possible to build a nationwide system for managing diverse threats – one with clearly defined competences between national and local authorities and a network of thousands of shelters that, despite their own limitations, can provide temporary protection to millions of people in critical situations.

Author: Natalia Matiaszczyk