By Damian Flanagan

You may be familiar with the Juzo Itami film, “Tanpopo” (1985), whose picaresque plot revolves around the subject of a woman setting up a ramen shop and attempting to discover the recipe for the most flavoursome bowl of noodles imaginable. The film sagely counsels that there are many elements to bringing together the perfect dish: the noodles; the meat and vegetables; the broth; not forgetting the ambience of the shop. The final climax of “Tanpopo” is reached when the customers simultaneously slurp down their bowls to the final drop.

Ramen is a serious business. A professor of Japanese at Cambridge University, Barak Kushner, even has a sideline in ramen research and has hosted ramen evenings in the formal hall of his college. Some might argue he should make ramen research his central study.

But I have no need of such cinematic and academic investigations, as many years ago I discovered the best ramen restaurant in the world. It was conveniently located only 300 metres from where I was living, on Route 2, the highway leading from Osaka to Kobe.

The shop was small and independently owned. It had an open kitchen and a select menu, though I only ever ate about three items from it. But hands down, their crowning glory was their “champon ramen”, which was a creation so miraculous it should have won at least five Michelin stars (out of a possible three).

As far as I can work out, there seem to be two competing strains in the ramen world, like two branches of the same religion. One of them — let’s call them the Puritans – insist that ramen is something which places a sliver of pork and bamboo shoots on a bed of noodles and only attempts very slight variations on these things: sometimes introducing an egg or possibly two slices of pork for the famished or greedy.

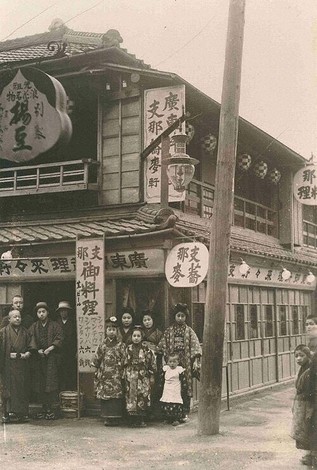

Rairaiken, supposedly the first ramen shop, founded in 1910 by Kan’ichi Ozaki in the Asakusa district of Tokyo. (Public domain.)

In opposition to the Puritans are the Catholic branch of the Ramen Church, who preach that far more adventurous things — like curried flavours and all manner of meats, fish and vegetables — can be used to accompany the noodles. “Champon ramen”, meaning a mix of everything, is the ultimate coming together of all possibilities, where a great number of different ingredients are brought joyously together in the bowl.

The tradition home of “champon Ramen” is Nagasaki, as ramen is itself originally a Chinese import that came to Japan via port cities like Nagasaki and Yokohama. But I have eaten a few champon ramen in Nagasaki and I can firmly declare that they are nowhere near as good as the bowl waiting for you at the place 300 m from where I live on Route 2.

The miraculous thing about the champon ramen I used to order was not just that it was a complete and very fulsome meal, nor even that it was highly nutritious, but also that it was astonishingly cheap. A giant bowl stuffed to the brim with flavoursome ingredients would only cost 850 yen or about $5.80. In England I imagine it would cost at least three times as much.

Very often the first thing I wanted to do when I returned to Japan was go to this ramen shop. I went there for over 20 years and at all times of day and night, because it never seemed to actually close, or at least it appeared to be attuned to my nocturnal rhythms. Sometimes I would go there on a Friday evening and have a champon ramen to set me up for the night ahead and sometimes I would go there on Sunday afternoon and have a champon ramen as the perfect hangover cure. I would slaver the side of the bowl with mustard and let the broth gradually taken on a mustardy tang. Once or twice I attempted to branch out and order a side of spring rolls, but soon discovered it was too much — the ramen covered all your epicurean needs.

And then, to my horror, I returned to Japan one time and discovered that the ramen shop had closed and been turned into a pet grooming store. I almost felt that I might need counselling to cope with the loss.

No bowl of ramen I tasted afterwards was ever anywhere near as good. Paradise had been lost. I associated that ramen shop amongst the short list of things treasured from my youth that had been wrenched away from me for some reason or another.

Years passed. And then one day I happened to be chatting to a neighbour in Japan and somehow or other mentioned, with wistful nostalgia, the lost ramen shop. Whereupon the neighbour amazed me by telling me that the shop had not exactly closed but merely moved to a different location and been taken over by a former employee (a “deshi” or student of the ramen master), and still served virtually the same menu as before and even went by the same name. Amazingly, the new ramen shop was only about 150 meters from the old one, but on a road I rarely passed down.

And so, after a gap of several years, I rushed down to the new version of my ramen shop and had the prized champon ramen placed down in front of me once more. Is there any feeling quite like that of eating something you once loved, but have concluded you will never eat again? Would the real thing pale in reality compared to the bowl of precious memory? And yet I can still report that it remains the best ramen in the world, peerless amongst its competitors, and that I slavered it with mustard and drank it down to the final drop.

(This is Part 70 of a series)

In this column, Damian Flanagan, a researcher in Japanese literature, ponders about Japanese culture as he travels back and forth between Japan and Britain.

Profile:

Damian Flanagan is an author and critic born in Britain in 1969. He studied in Tokyo and Kyoto between 1989 and 1990 while a student at Cambridge University. He was engaged in research activities at Kobe University from 1993 through 1999. After taking the master’s and doctoral courses in Japanese literature, he earned a Ph.D. in 2000. He is now based in both Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture, and Manchester. He is the author of “Natsume Soseki: Superstar of World Literature” (Sekai Bungaku no superstar Natsume Soseki).