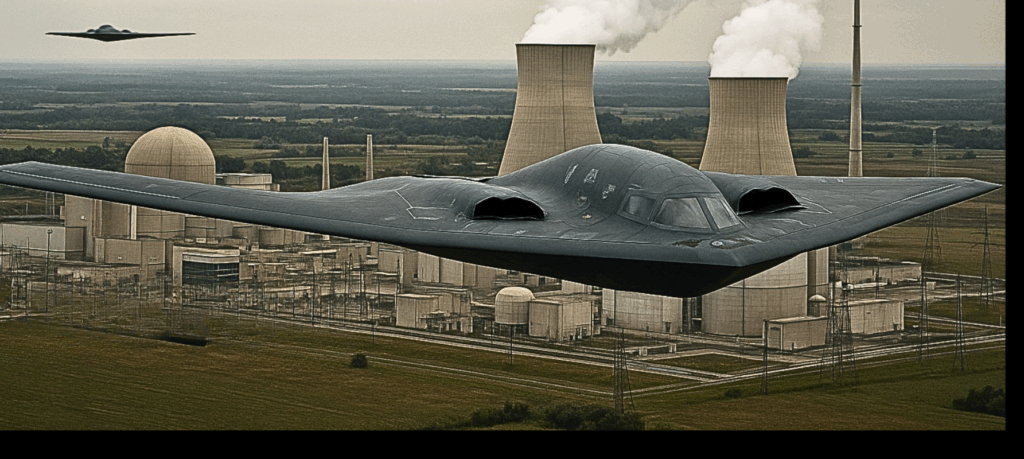

The recent joint US-Israel strikes on Iran’s nuclear enrichment facilities mark more than a tactical blow to Tehran, they represent a strategic turning point for nuclear aspirants worldwide. Fourteen GBU-57 massive ordnance penetrator (MOP) bombs and around 75 precision-guided munitions were used in operation Midnight Hammer, targeting nuclear facilities in Fordow and Natanz. In the wake of this precision operation, future proliferators are now on notice; if you plan to join the nuclear club, prepare to take a hit before you even cross the threshold.

Historically, states pursued nuclear weapons under the protective assumption that deterrence begins once a program reaches maturity; that is, when nuclear devices are assembled, tested, or deployed. To some extent all nine nuclear weapon states achieved that level of deterrent threshold during their proliferation stages. Iran had not achieved such maturity. Furthermore, when looking at the region historically the Israeli attack on Iraq’s Osirak reactor in 1981 and the 2007 strike on Syria’s Al-Kibar site both hinted at a willingness on the Israelis’ part to act preemptively to stop regional proliferators.

But the scale and coordination of this most recent strike go further. It sends a global message that enrichment facilities themselves, when capable of being targeted and penetrated by American GBU-57 bombs, inherently means that once you are closing in on enrichment, your facilities are fair game. This will be the truest when referring to adversaries of the US and its alliance network. It remains to be seen what would take place if an ally of the US were to proliferate nuclear weapons in this modern era without its consent.

This shift has profound implications for the future of proliferation. Any adversarial state aspiring to build nuclear weapons will now face a new strategic prerequisite: it must first develop the defensive capability to withstand a preemptive strike before it can even hope to proliferate successfully. That means constructing extensive, deeply buried underground facilities, tunnel networks, and hardened bunkers. They must be capable of surviving the US military’s most sophisticated bunker-busting munitions. It also means investing in robust air defenses, redundancy, deception, and a level of operational secrecy that rivals the most advanced intelligence agencies in the world.

Not every state can afford this. Proliferation is already an expensive and politically risky endeavor. The need to develop advanced passive defenses only compounds those challenges. Most would-be proliferators simply will not have the financial or technical wherewithal to defend their nuclear infrastructure at such a level, especially in the early, vulnerable stages of enrichment.

Iran, of course, will likely try again. The Islamic Republic has proven resilient, adaptive, and committed to achieving strategic parity with its adversaries. Unless it develops an indigenous system of defenses that can shield its critical infrastructure from aerial bombardment, future attempts will likely meet the same fate as the current one. Even if Iran builds bunkers and tunnel systems deep enough to shield its centrifuges, it will still face challenges of concealment, resource constraints, and foreign intelligence penetration.

The broader lesson here is stark; the window of opportunity for slow, open, or vulnerable proliferation may be closing. In the post Iran–strike era, nuclear aspirants will have to prepare for war before they prepare for the bomb. The cost of entry into the nuclear club has just gone up, not only in material terms but in strategic risk. Any state hoping to proliferate must now assume it will be struck before it succeeds.

This may serve to slow the pace of proliferation, but it could also make it more dangerous. Proliferators who internalize the lessons of the Iran strike may respond with greater urgency, opacity, and desperation. They may forgo the traditional step-by-step approach in favor of crash programs hidden deep underground or even move toward asymmetric hedging strategies that involve acquiring key technologies without crossing visible red lines. In such an environment, the risk of miscalculation on all sides grows.

The strike on Iran may therefore reduce the number of proliferators in the long run. But for those that do try, the game has certainly changed. As Stephen Cimbala recently argued, the precedent set by the Midnight Hammer strike on Iran should not be viewed in isolation. It marks a return to kinetic counter-proliferation under conditions of rising global instability, where deterrence is increasingly challenged by uncertainty and misperception.

In parallel, Peter Huessy emphasizes that restoring deterrence requires more than just missile defense or military strikes; it demands clarity of will and credible commitment to prevent nuclear breakout by adversaries.

Together, their analyses suggest that the US-Israel strike was not just about denying Iran the bomb, but it was also about reestablishing the normative firebreak against nuclear proliferation. The broader message is unambiguous: in an era where deterrence is fraying, those who wish to proliferate must now calculate not only how to build a bomb, but also how to survive the storm that will precede it.

If Iran is the test case, the future of proliferation will be shaped as much by preemption as by prevention, and only those with the means to withstand a midnight hammer will have any chance at joining the nuclear club. From now on, the path to the bomb runs through the rubble of facilities like Natanz and Fordow, and only the most prepared will make it out the other side.

Aaron Holland is a PhD Student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and an analyst at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies. All views expressed are the author’s own.

Aaron Holland

Aaron Holland is an Analyst at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies.