In late July last year, the Yalu River flooded for the first time in 60 years, devastating three northern provinces: North Pyongan, Jagang, and Ryanggang. Thousands died or disappeared as floodwaters swept away farmland, railroads, and roads. The disaster was made worse when operators at the Supung Dam opened floodgates multiple times daily, and by landslides cascading down North Korea’s largely barren mountainsides.

The flooding hit all three provinces hard, including the border city of Sinuiju in North Pyongan province. Entire mountainsides collapsed, mudslides erased whole villages, and destruction seemed to strike every valley. But the government’s response tells a story of stark inequality.

Sinuiju: a showcase recovery

After the floods, North Korea immediately deployed thousands of youth shock brigade workers to Sinuiju’s Wihwa Island area. For six months, they worked around the clock to build hundreds of apartment buildings near four Yalu River islands. Since February, they’ve been constructing what they claim are the country’s largest greenhouse farms on Wihwa and Taji islands—projects clearly designed to be visible from China.

Ryanggang province: forgotten and abandoned

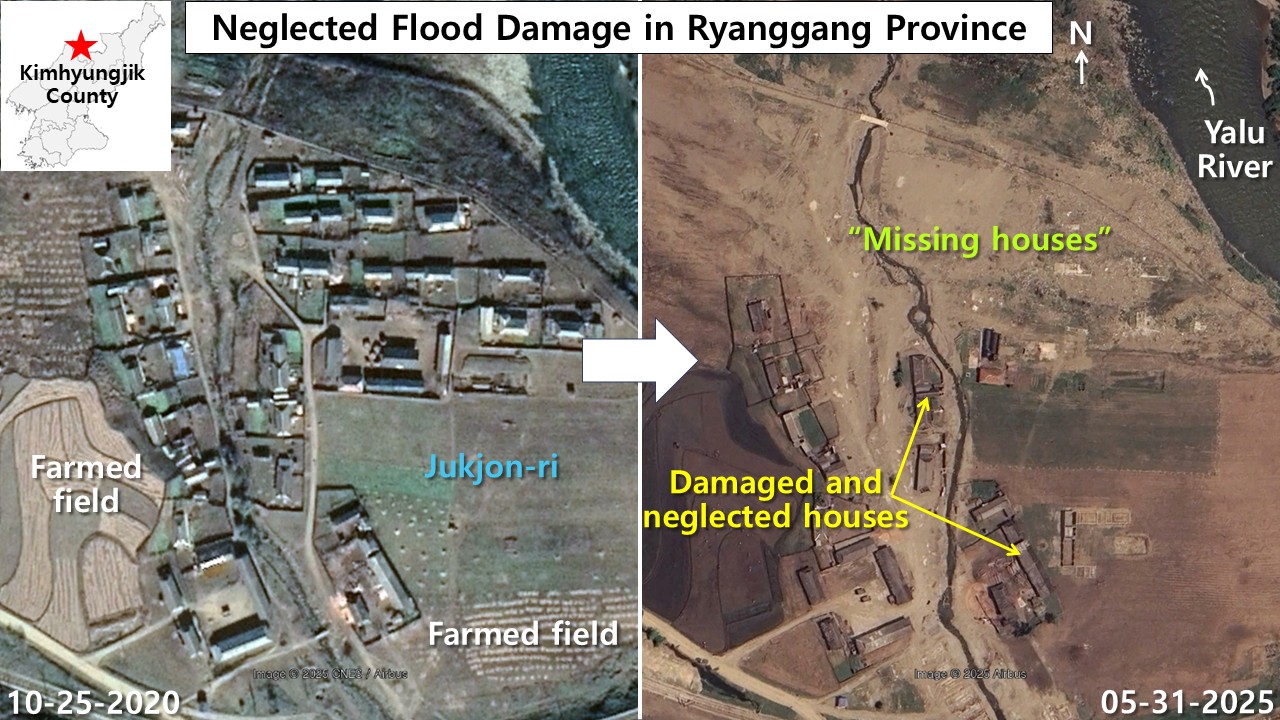

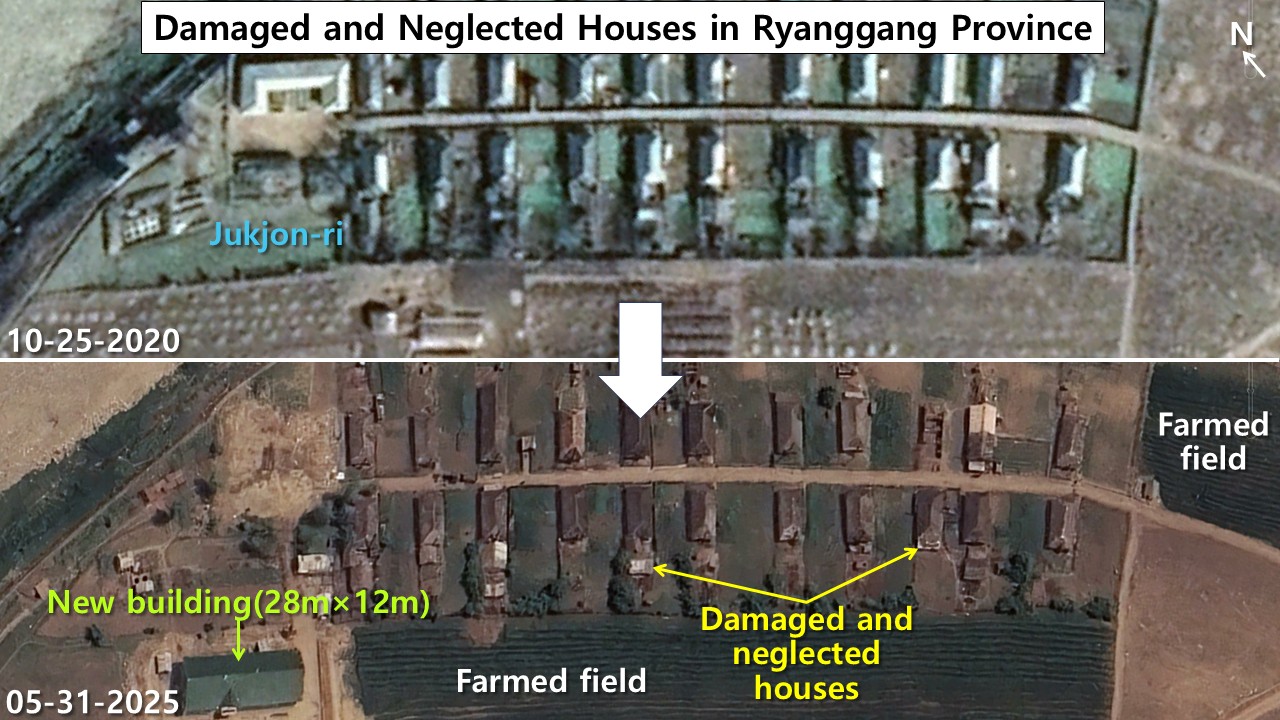

Using high-resolution satellite imagery, I examined the flood zones one year later. The contrast is striking. While Sinuiju has been rapidly rebuilt, remote areas of mountainous Ryanggang province—where hundreds of homes and entire villages vanished—remain in ruins.

In Jukjon-ri, Kimhyongjik county, Ryanggang province, the village was severely damaged by last summer’s great flood, and the areas where houses disappeared remain abandoned, still covered only with sand. /Photo=Google Earth

In Jukjon-ri, Kimhyongjik county, Ryanggang province, the village was severely damaged by last summer’s great flood, and the areas where houses disappeared remain abandoned, still covered only with sand. /Photo=Google Earth

In Jukjon village, located in Kimhyongjik county along the Yalu River, about 30 of the original 60 homes simply vanished in the floods. The remaining houses have sat damaged for nearly a year, their walls standing roofless while sand covers where the village once stood. (Kimhyongjik county was originally called Huchang but was renamed after Kim Il Sung’s father, following North Korea’s tradition of honoring its supreme leaders.)

Nearby Jangpa village tells an even starker story. This once-cozy community of roughly 30 homes has completely disappeared, buried under sand. The surrounding farmland was also washed away, leaving behind a desolate wasteland.

After the great flood, Jangpa-ri in Kimhyongjik county, Ryanggang province, has the entire village disappeared and is still covered only with sand. There are no signs or traces of flood recovery efforts. /Photo=Google Earth

After the great flood, Jangpa-ri in Kimhyongjik county, Ryanggang province, has the entire village disappeared and is still covered only with sand. There are no signs or traces of flood recovery efforts. /Photo=Google Earth

In Gumchang village, most of the 40-50 homes were destroyed. A large new building (40 by 12 meters) has been erected, with only a few smaller structures remaining. Strangely, satellite photos show that fields next to the village have been plowed, suggesting people are still working the land. I can’t determine where displaced villagers were relocated, but they may be living communally in the large new building while continuing to farm nearby areas.

Gumchang-ri in Kimhyongjik county, Ryanggang province, was also heavily damaged by last year’s great flood. The entire village disappeared and only one large building stands alone. /Photo=Google Earth

Gumchang-ri in Kimhyongjik county, Ryanggang province, was also heavily damaged by last year’s great flood. The entire village disappeared and only one large building stands alone. /Photo=Google Earth

Back in Jukjon, fewer than 30 damaged homes remain abandoned since the floods. A warehouse-like building (28 by 12 meters) has been built, and the agricultural land in front of the village shows signs of cultivation. This suggests that either people are living in their damaged homes or sharing the new communal building.

In the mountainous area of Jukjon-ri, Kimhyongjik county, residential houses damaged by the great flood remain abandoned. Long furrows are visible in the farmland in front of the village, and green vegetation that appears to be crops is growing, indicating traces of agricultural activity. /Photo=Google Earth

In the mountainous area of Jukjon-ri, Kimhyongjik county, residential houses damaged by the great flood remain abandoned. Long furrows are visible in the farmland in front of the village, and green vegetation that appears to be crops is growing, indicating traces of agricultural activity. /Photo=Google Earth

A tale of two priorities

The satellite images reveal a vast disparity in how North Korean authorities approach reconstruction. The gap between urban and rural recovery efforts is as wide as “heaven and earth.”

Sinuiju received massive attention because it’s North Korea’s gateway city, handling 80% of trade with China and ranking as the country’s second or third most prosperous city after Pyongyang. The market economy has taken deeper root there than anywhere else, with most residents earning their living through China trade activities. When disaster struck, Kim Jong Un showed intense personal interest, mobilizing youth brigades to quickly build hundreds of high-rise apartments.

Meanwhile, Ryanggang province—whose name means “two river province” after the Yalu and Tuman rivers that border it—continues to serve as a place of internal exile. Known for having the Korean Peninsula’s harshest terrain, with Mt. Paekdu dividing the two rivers, this remote region appears completely outside the interest of the country’s leadership.

One year after the floods, high-resolution satellite photos show no signs of reconstruction in these mountain areas, no facilities to shelter displaced families—a stark contrast to the showcase recovery visible in prosperous Sinuiju.