It’s been more than 80 years since the first licensing trust was established in Aotearoa. So why do they still exist – and are they past their use-by date?

When New Zealanders cast their ballots in the local elections over the next six weeks or so, residents of 16 different areas across the country get a vote that most of us don’t. These areas all play host to community-led organisations known as liquor licensing trusts, which control – and in some areas have a total monopoly over – the sale and supply of alcohol. Local communities get to vote for the trustees of these trusts every three years, at local elections time.

Licensing trusts have been operating in New Zealand since the 1940s, when they were created with the purpose of ensuring liquor sales and community wellbeing could go hand in hand by returning profits from liquor sales to the community. But 81 years on, our liquor laws, and society in general, have changed dramatically – so, do we still need them?

Hang on… is it bad that I never even knew this was a thing?

Nah, you’re in good company, because most New Zealanders aren’t living in trusts-run communities – I didn’t realise trusts existed until I moved to the West Auckland suburb of New Lynn in my early 20s. Maybe it’s helpful to start at the beginning: Aotearoa’s first trust was established in 1944 in Invercargill, a city where there had been prohibition since 1905. In 1943, 60% of Invercargill voters elected to overturn the ban on alcohol, with votes from soldiers fighting overseas in the second world war making up a big chunk of that 60%. Those who voted to keep prohibition demanded a recount, but the soldiers’ voting papers had been destroyed somewhere in the Middle East, so the result was confirmed and booze was back.

Amid concerns around liquor flooding back into the community, central government stepped in with the Invercargill Licensing Trust Act 1944, loosely based on a British scheme established during the first world war. Three years later, Masterton became the second town to follow suit with its own trust law, and in 1949 the Licensing Amendment Act was passed to allow polls to be held on whether a trust could be established (or discontinued) across the country. In the decades that followed, 28 more trusts were set up.

The last licensing trusts were established in Terawhiti in the Wellington region and Flaxmere in Hawke’s Bay in 1975, and only the latter of those two has kept the system. Since then, our legislation has made it easier to access alcohol, with the Sale of Liquor Act 1989 allowing for supermarkets to sell alcohol everywhere that doesn’t have a trust. Invercargill remains the home of the longest-running trust, with trusts also still running in Mataura near Gore, Clutha and Ōamaru in Otago, Geraldine in the Timaru district, Cheviot in North Canterbury, Rimutaka in Upper Hutt and Te Kauwhata in Waikato. Auckland still has trusts in Waitākere and Portage (a collection of West Auckland suburbs), Wiri in South Auckland, Birkenhead on the North Shore and Mount Wellington in the east of the city.

Some of these trusts have since broadened their operations to include housing and supermarkets, as well as gaming (aka gambling), among other businesses.

OK! I think I get it – if you live in a trust area, you can only buy alcohol from the trust, right?

Well, not quite – only three of the 14 remaining licensing trusts in Aotearoa hold a total monopoly over the sale and supply of alcohol in their community, while most now operate alongside private competitors. In the majority of areas with licensing trusts, punters have the option of heading to a trust-owned venue or just picking up a bottle from the supermarket.

A Trusts liquor outlet in West Auckland (Image: The Trusts)

The Waitākere and Portage licensing trusts in West Auckland (known jointly as the Trusts), and those in Invercargill and Mataura in Southland, however, have a total monopoly, with exclusive rights over operating bars, pubs and bottle stores.

So what are some of the arguments in favour of trusts?

As trustees are elected by the public, decisions made by the trust should in theory be reflective of the community’s aspirations and needs, rather than the wants of a corporation.

At least some profits – the exact amount depends on the trust – are returned to the community. For the Trusts in West Auckland, the divvying of funds looks like multiple $20,000 grants, which in 2024 were given to the likes of Te Pou Theatre Trust, Hoani Waititi Marae, West Auckland Youth Development Trust, EcoMatters Environment Trust and various other community organisations.

And it’s not just the liquor sales – trusts that hold a Class 4 licence under the Gambling Act 2003 must ensure that 40% of all profits made from gaming machines are returned to the community.

Profits made from gaming machines can also be turned into community grants.

There’s also the public health aspect that comes into play – by being able to control who holds a liquor licence and their times of trade, communities are kept safer (in theory) from public harm caused by alcohol use.

So what are the downsides?

Well, there’s a lot of debate over whether communities actually benefit from the trusts. Not all trusts are created equal in terms of how much money is going back to the community: in Invercargill, a city of 57,600, the town’s licensing trust returned over $5.3m in community funding in the financial year ending 2025, while in the 2023/2024 financial year, the Trusts returned $1.1m back to their community of around 300,000. The Trusts’ CEO Allan Pollard’s $580,000 salary has also been a point of contention for anti-trust punters, as have allegations of dysfunction, mismanagement and a lack of transparency in certain trusts.

Then there’s the argument that licensing trusts stifle community development. Consumers living within a total liquor monopoly have less choice, and there’s less pressure for their local liquor outlet to change the consumer experience – meaning these punters might just be taking their money somewhere else. Even with a licensing trust that doesn’t have a full monopoly, independent competitors can face contractual barriers such as minimum purchase volumes – if that puts a potential business off, it creates a less dynamic local hospitality sector.

Is there any way to change the status quo?

A petition signed by at least 15% of electors who live in a trust district can trigger a poll to challenge that trust’s monopoly rights. A petition in West Auckland in 2021 fell 934 signatures short.

Change can also come from within: a trustee can table a motion to trigger a referendum, which needs to get majority support from the trust’s members. Motions were tabled in both West Auckland trusts earlier this year by trustees affiliated with the West Auckland Licensing Trusts Action Group, but they failed to get majority support. At election time, candidates will make clear their stance on the monopolies of the trusts they’re running for, so electors in their districts can vote accordingly.

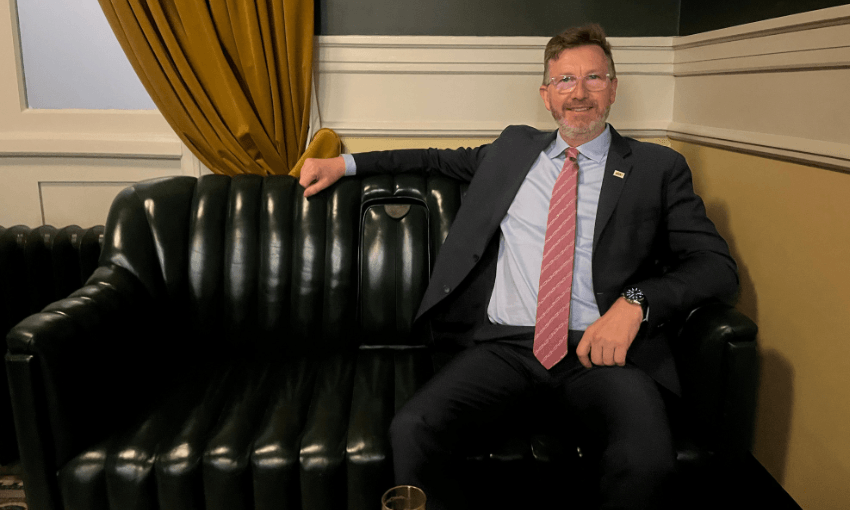

Act MP Simon Court wants to abolish the monopoly on liquor sales held by licensing trusts.

Alternatively, central government could lead the charge. Act MP Simon Court has a member’s bill in the biscuit tin that, if passed, would abolish the monopoly on liquor sales in West Auckland, Invercargill and Mataura. In early August, Court – who hails from Te Atatū – told The Spinoff that removing the monopoly in West Auckland specifically would help grow the area’s hospitality industry by providing more options for locals, and a potential nightlife scene helped by the area’s community of creatives. “There’s nowhere for them to play locally, where they can set up and we can go have a beer and watch the band,” Court said. “The barrier, as I see it, is the liquor licensing monopoly … We can keep the trust, we just want them to perform better and deliver back to their community.”