FROM THE CENTER of downtown Boston, getting to a hospital or health center can be as straightforward as walking a few blocks in any direction. Within 30 minutes of drive time from Tufts Medical Center, there are 23 other acute care hospitals, according to state data.

In more far-flung regions of the state, a long drive or a patchwork of transit modes can stand between someone in need of health care and the place best able to provide it. Within 30 minutes of Berkshire Medical Center, the midsized nonprofit community hospital in Pittsfield across the commonwealth from Boston, there are no other acute care hospitals. Same for Cape Cod Hospital.

While most health care analyses rank Massachusetts at the pinnacle of state health system performance – consistently sitting among the states with the best health care coverage and access, highest childhood vaccination rates, highest health insurance coverage, lowest infant mortality, and fewest premature avoidable deaths – geographic barriers persist. And the looming promise of Medicaid cuts – plus an already overburdened system in regions like southeastern Massachusetts, where staffing shortages and higher rates of uninsurance are exacerbating health care costs – casts a pall over the comparatively sunny overall health stats.

“We know that patients face many barriers to accessing care, and geographic distance is one of those barriers,” said Amie Shei, president and CEO of the Worcester-based Health Foundation of Central Massachusetts. “It’s not simply the number of miles from point A to point B along a straight line, it’s the particular options this person has access to.” (Shei is on the board of MassINC, CommonWealth Beacon’s publisher.)

The state has several ways to measure and identify geographically vulnerable medial areas. One measure tracked by the Department of Public Health is health workforces shortages, which is often a measure of geographic vulnerability because people in areas with fewer doctors and health resources have fewer care options within a reasonable distance. Five Massachusetts regions are federally designated as geographic areas with a shortage of providers: Dukes County, a combined stretch of Hampden and Hampshire counties, Nantucket County, the North Quabbin region of Franklin and Worcester counties, and the Southern Berkshires.

Similarly, the state has 46 “medically underserved areas” – geographic areas and with a lack of access to primary care services – almost all of which have held the designation for around three decades and are scattered across the state from Berkshire to Dukes counties in rural and urban centers.

Travel and geography alone are not the main driver of access issues, but in a cost- and staff-strained health care environment, it’s a part of “all of the above” calculation that explains why Massachusetts residents sometimes go without care.

Even if the direct financial hurdle to medical care can be cleared, someone may need to have family or friends who can give them a ride, or have public transit that’s reliable and can get the person near enough to their care facility in time, or secure child care while half a day is spent traveling to and from appointments.

“All of this takes mental energy,” noted Shei. “It takes access to technology and being able to navigate a complex system. The more barriers you layer on, the more likely it is that someone may delay or forego care.”

In the 1960s, Massachusetts boasted well over 100 hospitals, scattered around the state but still centered in Eastern Massachusetts. Through closures and consolidations, the number plummeted to just 65 acute hospitals in 2023, according to state data. While a few hospitals have re-opened since 2023, the Steward Health Care bankruptcy crisis revealed serious cracks in the system and led directly to community hospital closures in Boston and Ayer.

Since the 1990s, the economic landscape of health care has experienced “rapid and continual change,” Cheryl Damberg, director of the RAND Center of Excellence on Health System Performance, testified before Congress in 2023. “Consolidation in the health care market is endemic and is happening in all parts of the health care delivery system. Across the United States, health care markets are dominated by a few large players, and the footprints of these players continue to expand.”

Following a wave of consolidation in the early- and mid-1990s, there were 1,573 hospital mergers from 1998 to 2017 and another 428 hospital and health system mergers announced from 2018 to 2023, according to KFF research. The share of community hospitals that are part of a larger health system also increased from 53 percent in 2005 to 68 percent in 2022.

“Hospitals are not interchangeable parts in a health care machine,” Boston University health care analysts Alan Sager and Deborah Socolar warned in 2002, advocating for saving the Deaconess-Waltham Hospital, which closed the next year. “They have deep ties to doctors, programs, patients, and communities.”

In other words, when a hospital closes, it creates a chain reaction in the community. Nearby residents will need to find alternative health care providers. Experts like Sager and Socolar warn that ambulance travel time will increase, and emergency room and inpatient crowding will worsen at surviving hospitals. The more closures, the more strain.

For those who can afford coverage and want to access it, geography can be a hurdle. Acute health care facilities remain tightly centered around the Greater Boston hub. This is, of course, the most populous region of the state, served by dense webs of public transit, and is home to dozens of hospitals, clinics, and educational institutions – the heart of the state’s famed meds and eds economy.

Meanwhile, Southeastern Massachusetts and the Cape and Islands report some of the highest levels of uninsurance in the state, have fewer available ICU beds and acute care centers, and are afflicted by a clinician shortage more pronounced than the state as a whole.

“Health care access issues are multifaceted, and residents in the Commonwealth can face compounding effects from challenges accessing their care on top of the known financial barriers to affording care,” said Health Policy Commission Executive Director David Seltz. “This leaves lower-income and rural families particularly vulnerable to delaying or foregoing needed care.”

In its most recent report on access, released last June, the Center for Health Information & Analysis (CHIA) found that 41 percent of Massachusetts residents surveyed reported difficulty accessing care in 2023. The most common issue was an inability to get an appointment with a doctor’s office or clinic as soon as needed (25.6 percent), followed by issues getting appointments withs specialists (23.3 percent), the doctors’ office or clinic not accepting new patients (19.1 percent) or their insurance type (12.6 percent), and being unable to get an appointment due to transportation issues (4.4 percent).

But the transit issues became much more pronounced as income levels drop and mobility or health issues worsen. More than one in 10 residents reported transportation-related difficulties if they had a family income at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty line ($44,367 for a family of four in 2025) or if they reported being in fair or poor health or having activity limitations.

In its 2022 Community Health Needs Assessment, Baystate Franklin Medical Center, Franklin County’s only acute care hospital, identified “access to transportation arose as an overwhelming need” in the communities served by the facility. The 107-bed, not-for-profit hospital serves the most rural county in the state. Though the county’s regional transit authority covers the largest service area of the state’s RTAs – some 1,121 square miles – the medical center noted that bus routes do not reach the smaller towns and traveling by bus outside of the area requires transferring between regional transit authorities. (For the 118 residents of the tiny town of Monroe in the northwest corner of Franklin County, for example, the closest hospital for the past decade was Baystate Franklin Medical Center, only accessible by an hour-long car ride.)

“Those without a car said they sometimes find they simply cannot get where they need to go when they need to get there or find themselves with long waits for the next bus to take them home,” the report stated. “The lack of transportation exacerbates inequities, as people miss out on education, work, and help in places they cannot reach without a car.”

A June 2024 presentation from the Health Policy Commission reviewing health access reports over the past 15 years noted similar findings. Residents of more rural regions faced physical barriers, such as available and affordable public transportation, to accessing needed substance use disorder treatment as instances of substance abuse spiked across the state.

According to the commission’s research, commercially-insured residents living in the lowest-income areas of the state were much more likely to have no primary care visits than those living in higher income parts of the state, with the disparity especially pronounced among children. While geographic access to care may not be the only factor explaining this finding, the commission noted, it is likely an important contributor.

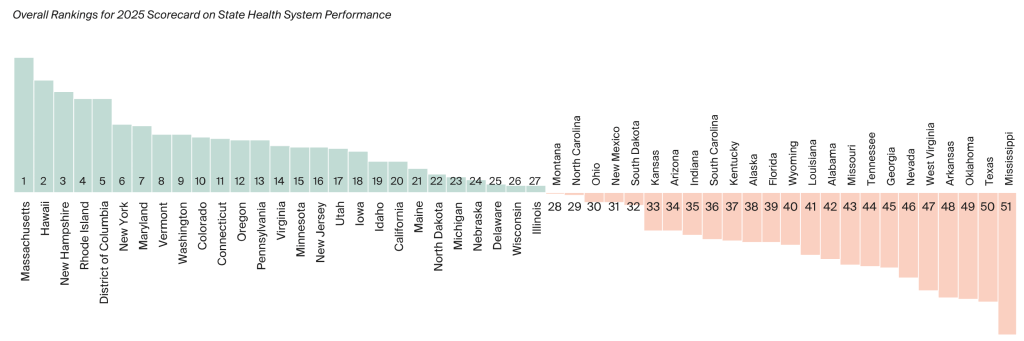

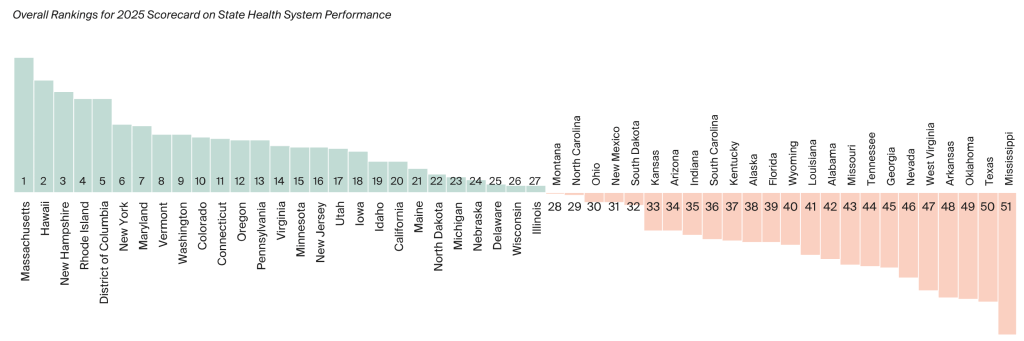

Even as Gov. Maura Healey touted recent state health rankings from the Commonwealth Fund, which released its 2025 nationwide scorecard in June, the governor took note of the federal challenges that are looming.

“Massachusetts is yet again the best state in the nation for health care,” she said in a statement at the time. Despite significant progress, “we know there is still more work to be done, especially as President Trump and Congressional Republicans’ are trying to take away health care from hundreds of thousands of Massachusetts residents. We’re going to continue our work to make sure everyone can access high-quality, affordable health care, and speak out against attempts to take us backwards.”

Overall Rankings for 2025 Scorecard on State Health System Performance from The Commonwealth Fund report.

Overall Rankings for 2025 Scorecard on State Health System Performance from The Commonwealth Fund report.

Despite the rosy outlook provided by think tank rankings – and before the cuts to Medicaid were threatening to exacerbate the gulf between the haves and have nots – digging below the surface of the state-level stats shows a Commonwealth in which residents face very different health care realities.

Take, for example, the ratios of direct patient care physicians. In 2023, Massachusetts had 442 direct patient care physicians, who are usually paid directly for services rather than through insurance, per 100,000 residents, ranking first nationally compared to the national average of 278.0. But the spread by county was immense. Suffolk County, which includes most of Greater Boston’s many health institutions, boasts 1,277.4 direct patient care physicians per 100,000 residents, but several counties drop below the national rate. That includes Essex County with 219.2, Plymouth County with 173, Bristol County with 147.2, Franklin County with 143.6, to a low of 89.7 in Nantucket County. Similar gaps exist in primary care physician ratios.

Although some regions have fewer health facilities available, the ratio of physicians remains above the national average even with significant geographic spread because the county population itself is lower.

Measuring only by physicians per person or drive distance to a hospital, though a useful baseline, can miss the difficult realities of accessing care in very remote areas, forcing locals and their representatives into years-long fights for better care closer to home.

This was the case for the North Adams area, perched in the northwest corner of the state in the far reaches of the 130,000-resident Berkshire County. After its regional hospital abruptly closed in 2014, the closure not only cut off residents from nearby health care. The Berkshire Eagle reported about 530 people lost their jobs in a matter of days.

A long bureaucratic process stood in the way of the facility opening as a critical access hospital, which would make it eligible to get federal Medicaid and Medicare funding. It was technically too close to the Pittsfield hospital 40 minutes away by car and to the hospital in Bennington, Vermont, which is about 30 minutes away by car but 2 hours and 45 minutes by public transit.

Since the site closed, locals and US. Rep Richard Neal advocated for about a decade for the federal classification that would bring care back to the areas. Neal said he finally was able to change the classification language because the mountainous area depends on a single lane highway, experiences difficult weather in the winter, and deeply needed a full-service critical access hospital.

“Most of the stories, overwhelmingly, across America, are about hospital closures,” he said at the re-opening in 2024. “America’s got a real challenge with rural health care. Today we celebrate this opening against all odds; this return is for all of you in Berkshire County.”

Though the loss of an entire hospital leaves a visible service dent in an area, contractions in specialized care areas also push patients to travel longer distances for services like maternity care or mental health supports.

Since 2014, 11 hospitals in Massachusetts have closed or filed to close their maternity services, according to Health Policy Commission data, and two birth centers in Beverly and Holyoke have closed. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s policy center reported in 2024 that New England nursing home closures have outpaced the rest of the country since 2010, with Massachusetts losing almost 10,000 nursing homes beds by 2023.

The loss of facilities often sparks furor from the surrounding communities, with mixed results. State officials opted not to save two former Steward Health properties – Nashoba Valley Medical Center and Carney Hospital – despite forceful objection.

Attempted state budget belt tightening put the Pappas Rehabilitation Hospital for Children in Canton, which serves disabled children, on the chopping block and would have redirected services and children. Though outcry halted the move for at least the next fiscal year, the facility’s long-term financial health is far from secure.

But community hospitals and state officials alike are bracing for an increasingly grim financial picture after the 2026 midterms.

In July, Congress passed and the president signed a sweeping tax and spend bill that cuts about $1 trillion of federal health spending over a decade, reversing efforts during prior Democratic administration to expand access through more robust Medicaid programming and the Affordable Care Act.

Up to 203,000 more Massachusetts residents could be left without insurance because of the bill, according to a new Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation report, putting even more financial pressure on the institutions providing care.

On an episode of The Codcast in August, Eric Dickson, president and CEO of UMass Memorial Health, painted a grim financial picture. Unless efforts are made to roll back or adjust the proposed cuts, the tax bill could create a hole of more than $100 million for the system that would then have to be made up by program cuts or finding a way to increase revenue, Dickson said.

“We’ll be greatly impacted by this,” he said. “How badly? Will they kick the can down the road? We don’t know? … We’re just doing everything we can to stay true to who we are, to shore up the organization as best we can today where we have an operating loss, such that we’ll be more prepared for what happens” next fiscal year.

The week after that podcast, UMass Memorial announced more service cuts through its affiliate Community Healthlink, which provides mental health, substance abuse, and homelessness services anchored in Worcester. The Fitchburg adult mental health service BUDD, or Builds Understanding and Develops Direction, program will permanently close on October 23.

In a statement, UMass Memorial Health said Community Healthlink “has spent the past several months assessing operations across its programs to support the organization’s long-term viability,” but the program “has struggled to maintain a consistent client census due to its specialized nature and closed referral system.”

Baystate Health, the largest health care system in Western Massachusetts, runs some of the only major hospitals in more rural counties like Franklin. Its chief financial officer told The Boston Globe in July that, on top of recent staff cuts and significant financial loss, the medial group expects an annual loss of $30 to $50 million based on their analysis of the tax bill.

Michael Curry, the president and CEO of the Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers, said the tax bill creates a dire conundrum for the state’s health care system.

Michael Curry, president of the Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers, speaks at the State House. (Image via Mass. Governor’s Flickr archives)

Michael Curry, president of the Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers, speaks at the State House. (Image via Mass. Governor’s Flickr archives)“It would be unsustainable without the federal partnership, the federal funds,” he told CommonWealth Beacon in May. “So, you cut programs, right? You might cut benefits, right?” Just because a person is pushed off Medicaid, he said, doesn’t mean the state is off the hook for costs, which only gets more expensive the more emergency services are used in place of regular care.

Losing out on immediately and easily accessible health care facilities leaves gaps in essential care coverage. Geographic access issues also increase the odds that a patient would opt for an emergency room visit rather than seeking primary care.

“Limited access to primary care can lead to potentially avoidable [emergency] and inpatient hospital use and associated higher spending, as well as worse patient outcomes, especially for patients managing chronic conditions,” the Health Policy Commission noted in January. “Patients with distance, transportation, or language barriers to accessing primary care are also more likely to use the [emergency department] for non-emergent conditions.”

While Massachusetts rates among the top states for access and affordability – a combined category – in the Commonwealth Fund report, it ranks 35th in avoidable hospital use and cost. This measures factors including avoidable emergency room visits, preventable hospitalizations, employer-sponsored insurance and Medicare spending per patient, and primary care spending as a share of total health care spending.

Some resources could, in theory, be accessible without needing to travel long distances from rural areas.

Telehealth services expanded dramatically during the Covid-19 pandemic. Two thirds of behavioral health care visit were over telehealth in 2022, the Health Policy Commission found, but a 2023 report found that more could be done to increase access for more rural and vulnerable populations.

Patients living in small town or rural areas were 8.3 percentage points less likely to use telehealth compared to urban residents, according to the report, and patients living in communities with better internet access were 5.5 percentage points more likely to be telehealth users.

For those who must travel for appointments, or would simply prefer in-person care, high cost is the most obvious impediment. But hidden costs are still expensive – in effort, in time, in delayed recovery, in system strain.

“Beyond system-wide obstacles like long wait times for appointments, difficulties or delays in receiving approvals for needed care, and increasing out-of-pocket costs and medical debt, even once an appointment is made, many patients struggle with barriers to accessing that care,” said Selz of the Health Policy Commission. “Individuals who cannot take time off during a workday or secure childcare for an appointment struggle to find providers who are available outside of regular business hours. Transportation – either trying to utilize public transportation or relying on support networks to get to appointments – can pose a real geographic challenge.”

“These difficulties compound and make it harder for people to access the care they need,” he said, “deepening existing health disparities.”

Related