By Christopher M. Blanchard

Since the December 2024 collapse of the government of Bashar Al Asad, Syrians have pursued political and economic opportunities created by the end of the country’s twelve-year civil war. Internal tensions and external pressures pose obstacles to the country’s transition.

Interim president Ahmed Al Sharaa led a group long designated by the U.S. government as a terrorist organization. Interim authorities have outlined a five-year transitional constitutional framework after limited consultation with Syrian citizens. Elections are planned in September 2025 for a partially and indirectly elected legislative assembly. The government does not exercise control over all of Syria, with areas of the northeast under the control of ethnic Kurdish-led forces and areas south of the capital, Damascus, controlled by members of the Druze religious minority.

Authorities plan to delay elections in these areas. Turkish forces remain in parts of the north, while Israeli forces have moved into formerly demilitarized areas between Syria and Israel and into some Syrian territory near the frontier. Sectarian violence involving government forces, their backers, and members of minority communities has marred the transition in 2025, highlighting the interim government’s limited capacity to ensure security and impose discipline. In this context, some observers have expressed skepticism about the interim government’s commitments to inclusivity and the protection of all members of Syria’s diverse religious and ethnic fabric. Others have warned that opponents of the interim government may be exploiting communal tensions to advance their own agendas.

The Trump Administration has outlined a policy of conditional support for the interim government, pairing endorsement of its leaders’ calls for the maintenance of Syria’s unity and territorial integrity with insistence that they adopt a protective and inclusive approach toward all Syrian communities. The United States is supporting dialogue between the interim government and authorities in areas of northeast Syria under the protection of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-led coalition that has received U.S. security support since 2015. The SDF remains the principal U.S. partner in the fight against the Islamic State group in Syria. U.S. military forces are deployed in eastern and southern Syria, and are implementing Trump Administration directives to consolidate and streamline the U.S. military presence in the country. The United States and European Union have extended broad sanctions relief to the interim government in a bid to encourage investment and prevent economic collapse and humanitarian pressures from derailing the transition. Economic conditions across Syria have deteriorated since Asad’s fall, with energy shortages and financial pressures limiting recovery efforts. Announced changes to U.S. and international sanctions on Syria since May 2025 have create possibilities for more robust investment, trade, and economic growth, but Syrians are grappling with the negative effects of decades of misrule and sanctions amid the strife and destructive consequences of a decade-plus-long civil war.

Governance and security arrangements between Syria’s national government and de facto authorities in northeast and southern Syria remain a central dilemma for transitional leaders and the minority communities in these areas. Neighboring countries, including Turkey and Israel, are acting inside Syria in pursuit of their preferred outcomes. Turkey opposes Syrian Kurds’ aspirations for autonomy or decentralization, citing links between Kurdish elements of the SDF and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization. The PKK announced in early 2025 that it would dissolve and disarm. In March 2025, the SDF agreed in principle to integrate under the interim government’s authority, but SDF figures and others have criticized what they perceive as unilateralism by interim government leaders. Israel has used military force to destroy military equipment and weaponry across Syria since December and to enforce its desire to see Syria’s three southern provinces remain a demilitarized zone. Israel also has struck targets in southern Syria and in Damascus in what it describes as a bid to protect the Syrian Druze minority community. Israel-Turkey tensions over Syria also raise risks of confrontation.

In Congress, many Members welcomed the fall of the Asad government and the setbacks it has created for Iran and Russia. Members have debated U.S. policy toward the interim government, with some advocating for the elimination of remaining U.S. sanctions on Syria and others expressing concern about the intentions and actions of Syria’s interim leaders and calling for a more gradual and conditional approach. President Donald Trump has acted to remove many Asad-era sanctions on Syria using authorities delegated to the President by Congress; President Trump also has revised other Syria-related sanctions mechanisms to preserve his ability to impose new sanctions based on future developments in Syria. Bills introduced in the 119th Congress would variously rescind (e.g., H.R. 3941 and S. 2133) or amend (H.R. 4427) some laws providing for Syria-related sanctions and would appropriate funds for the conditional provision of foreign assistance in Syria (H.R. 4779) or authorize (H.R. 3838/S. 2296) or appropriate (H.R. 4016/S. 2572) military assistance to U.S. partners in Syria. Legislative questions for Congress include whether and on what terms to authorize and appropriate funds for U.S. assistance and security operations in Syria; whether and to what extent to revise or rescind laws providing for U.S. sanctions on Syria; and how best to influence executive branch policies and shape the decisions of Syrian authorities, and U.S. partners and adversaries.

Overview and Key Developments

The fall of the government led by Bashar Al Asad in December 2024 marked a dramatic end to a twelve year-long conflict in Syria and the conclusion of decades of tension between the United States and the Baath Party-dominated government of Syria, led by the Asad family.1 The Asad government’s hostility to Israel, attempts to dominate neighboring Lebanon, alignment with Russia, partnership with Iran, support for terrorist groups, and development and use of weapons of mass destruction had fueled tensions with the United States for decades. Forces and leaders associated with Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS, aka the Organization for the Liberation of Syria, see Appendix) toppled Asad and have exerted security control over most of western Syria (Figure 1). They also lead the country’s transition. HTS had severed its former ties to Al Qaeda and the Islamic State, but remained a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization until July 2025.

In January 2025, attendees at a “Victory Conference” of some anti-Asad armed groups appointed HTS leader Ahmed Hussein Al Sharaa (aka Abu Mohammed al Jawlani/Jolani/Golani), a U.S. Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT), as Syria’s interim president. Many individuals appointed to interim national leadership positions were HTS members or previously served in the HTS-backed Syrian Salvation Government. In conjunction with Sharaa’s selection as president, interim authorities rescinded Syria’s 2012 constitution and dissolved the former ruling Baath Party, the Asad-era legislature, and the former regime’s military and security forces. A brief and partial national dialogue preceded the issuance of a five-year transitional constitutional framework. In March 2025, a new cabinet (Table 1) expanded the interim leadership to include members of some minority groups. Indirect elections for a partially elected parliament are planned for September.

The authorities have declared the dissolution of all military factions, political, and civil revolutionary bodies and called for their integration into state institutions. Progress toward this goal has been uneven. The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—a Kurdish-led coalition that has served as the principal U.S. partner against the Islamic State—controls the northeast in partnership with an Autonomous Administration for North and East Syria (AANES). In March 2025, the SDF signed an agreement on integrating with national security forces by the end of 2025. The SDF and AANES seek guarantees of constitutional rights amid threats from the Islamic State and concerns about sectarian violence. Talks have yet to yield further agreement. Turkey and Syria’s interim leaders oppose autonomy for SDF-held areas, and Turkish concerns focus on SDF-links to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated terrorist group that is implementing plans to disband. Some southern areas home to the Druze religious minority remain outside national control. Druze groups have debated their relationship with the state, with sectarian clashes and Israeli military intervention in July 2025 driving wider calls for autonomy.

Syria’s unresolved internal tensions, the interests of regional and international actors, and the interim authorities’ limitations are presenting serious challenges to the transition. According to UN officials, clashes since March 2025 involving state forces, state-aligned armed groups, and some minority communities reportedly killed nearly 3,000 civilians and fighters and displaced more than 200,000 people. The violence has increased global scrutiny of the interim authorities’ capabilities and intentions.

Violence in Syria’s western coastal provinces in March and April followed attacks there on government forces by pro-Asad groups and featured retaliatory attacks on Alawite communities by government-aligned groups.2 In the wake of that violence, the interim government said it was redoubling its efforts to assert unified security command over armed groups and launched a fact-finding investigation that has delivered its report to the interim authorities.

Sectarian violence also erupted in southern Syria between members of Druze and Sunni Arab Bedouin communities in April, May, and July.3 The July conflagration in and around the predominantly Druze city of Suweida killed nearly 1,400 combatants and civilians, displaced an estimated more than 185,000 people, and prompted military intervention by Israel.4 A ceasefire has held, but is fragile.

Source: CRS using Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) reporting to Lead Inspector General, media and social media reporting and Esri and U.S. State Department data. All areas of influence approximate and subject to change.

Source: CRS using Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) reporting to Lead Inspector General, media and social media reporting and Esri and U.S. State Department data. All areas of influence approximate and subject to change.The Trump Administration has outlined a policy of conditional support for the interim government, endorsing calls for the maintenance of Syria’s unity and territorial integrity while insisting on inclusion and protection for Syrian minority communities. President Trump met Ahmed Al Sharaa in Saudi Arabia in May. U.S. officials have strongly condemned sectarian violence, supported de-escalation, and called for transparent investigations and accountability. U.S. officials have supported two dialogue tracks: one between the interim government and authorities in northeast Syria and one between the interim government and Israel. U.S. forces are deployed in eastern and southern Syria, and are consolidating their presence. The United States and European Union have extended sanctions relief to Syria’s government to encourage investment, prevent economic collapse, and ease humanitarian pressures.

In Congress, many Members have welcomed the fall of the Asad government and the setbacks it has created for Iran and Russia. Members have debated U.S. policy toward the interim government, with some advocating for the elimination of remaining U.S. sanctions on Syria and others expressing concern about the intentions and actions of Syria’s interim leaders and calling for a more gradual and conditional approach.5 President Donald Trump has acted to remove many Asad-era sanctions on Syria using authorities delegated to the President by Congress; President Trump also has revised other Syria-related sanctions mechanisms to preserve his ability to impose new sanctions based on future developments. Bills introduced in the 119th Congress would variously rescind (e.g., H.R. 3941 and S. 2133) or amend (H.R. 4427) some laws providing for Syria-related sanctions, direct the withdrawal of U.S. forces (S.J.Res. 6), appropriate funds for the conditional provision of foreign assistance in Syria (H.R. 4779), or authorize (H.R. 3838/S. 2296) or appropriate (H.R. 4016/S. 4921) funds for military assistance to U.S. partners in Syria.

Table 1. Syria: Selected Interim Authorities (As of September 4, 2025)

President of the Syrian Arab Republic/ Commander-in-ChiefAhmed Al SharaaMinister of Foreign AffairsAsaad Al ShaibaniMinister of DefenseMaj. Gen. Marhaf Abu QasraMinister of InteriorAnas Al KhattabMinister of FinanceMohammad Yusr BarniyaMinister of EconomyMohammad Nidal Al ShaarMinister of JusticeMazhar Al WeissMinister of EnergyMohammed Al BashirMinister of Public Works and HousingMustafa AbdulrazakMinister of TransportYarob BadrMinister of AgricultureAmjad BadrMinister of HealthMusaab Nazal Al AliMinister of Social Affairs and LaborHind QabawatChief of the General Staff of the Army and Armed ForcesAli Noureddine Al NasanGovernor of the Central Bank of SyriaAbdulqader HusriehSource: CRS, compiled from Syrian and international media reports. Subject to change.Note: According to a July 2025 UN report, “At least 9 out of 23 ministers are directly or indirectly linked to HTS, 4 of whom held military roles within the group.” See UN Document S/2025/482, July 24, 2025.

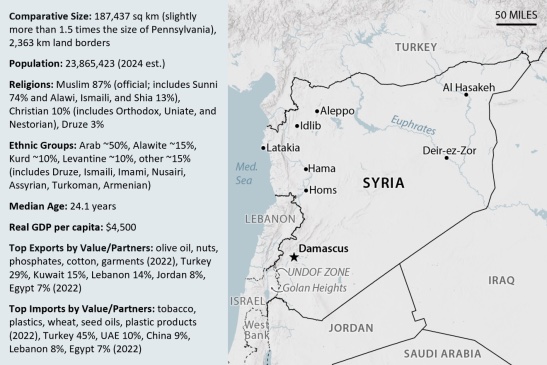

Syria: At a Glance Map and Data. Source: CRS. Using Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook data, February 2025.

Syria: At a Glance Map and Data. Source: CRS. Using Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook data, February 2025.Notes: The United States recognized the Golan Heights as part of Israel in 2019. UN Security Council Resolution 497, adopted on December 17, 1981, held that the area of the Golan Heights controlled by Israel’s military is occupied territory belonging to Syria.

Syria: Conflict Synopsis and U.S. Policy, 2011-2024

In March 2011, antigovernment protests broke out in Syria, in the midst of a wider trend of regional upheaval and challenges to decades of authoritarian rule. Violence escalated, and, in August 2011, President Barack Obama called on Syrian President Bashar al Asad to step down. Over time, the rising death toll from the conflict and the use of chemical weapons by the Asad government intensified pressure for the United States to assist the opposition.

In 2013, Congress debated lethal and nonlethal assistance to vetted Syrian opposition groups, and authorized the latter. Congress also debated, but did not authorize, the use of force in response to an August 2013 chemical weapons attack.In 2014, the Obama Administration requested authority and funding from Congress to provide lethal support to vetted Syrians for select purposes. The original request sought authority to support vetted Syrians in “defending the Syrian people from attacks by the Syrian regime,” but the subsequent advance of the Islamic State organization from Syria across Iraq refocused executive and legislative deliberations onto counterterrorism. Congress ultimately authorized a Department of Defense-led train and equip program for select Syrian forces to combat terrorist groups active in Syria, defend the United States and its partners from Syria-based terrorist threats, and “promote the conditions for a negotiated settlement to end the conflict in Syria.”6

In September 2014, the United States began air strikes in Syria, with the stated goal of preventing the Islamic State from using Syria as a base for its operations in neighboring Iraq. In October 2014, the Defense Department established Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) to serve as the military component of the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, a multilateral civil and military coalition of dozens of countries.

In 2015, the United States deployed military forces to Syria to counter the Islamic State and train local partner forces. Coalition and U.S. gains in Syria against the Islamic State after 2015 came largely through the assistance of Syrian Kurdish-led partner forces, but neighboring Turkey’s concerns about Kurdish forces in Syria emerged as a persistent challenge for U.S. policymakers. In 2017, the United States began providing arms to the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and the SDF, backed by U.S. forces, advanced on IS-held areas, seizing the IS stronghold of Raqqah in October 2017 and asserting control over the last IS-held areas of Syria’s eastern Euphrates River valley in March 2019.

In 2018, the U.S. intelligence community assessed that the conflict had “decisively shifted in the Syrian regime’s favor.”7 Remaining armed opposition forces (including groups linked to Al Qaeda) and civilians actively opposed to Asad were pushed into a shrinking geographic space in and around Idlib province in northwestern Syria. Turkish military forces remained present in Idlib and other areas of northern Syria, limiting advances by pro-Asad forces and preventing further displacement of Syrians to Turkey.

In October 2019, after President Trump signaled that U.S. forces would withdraw from Syria, Turkey launched a cross-border military operation attempting to expel Syrian Kurdish U.S. partner forces from areas adjacent to the Turkish border. President Trump briefly imposed sanctions on Turkish officials and negotiated a ceasefire that was later complemented by a separate agreement reached between Turkey and Russia to establish patrolled security zones. While U.S.-led coalition and partner forces focused on defeating the Islamic State in northern and eastern Syria, support from Russian, Iranian, and Hezbollah forces enabled the Syrian government to retake many areas of the country formerly held by the opposition. The United Nations (UN) sponsored peace talks in Geneva beginning in 2012, but the talks bore little fruit. Over time, military pressure on the Syrian government to make concessions to the opposition was reduced. By 2022, UN Special Envoy for Syria Geir Pedersen described the conflict as a “stalemate” with relatively fixed lines.8

In Idlib, Haya’t Tahrir al Sham distanced itself from Al Qaeda and the Islamic State, establishing and controlling a Syrian Salvation Government, retraining fighters into more formidable and capable units, and periodically clashing with Turkey-backed groups in control of other areas of northern Syria. In November 2024, HTS-led forces launched an offensive in response to escalating pro-Asad attacks, leading to the unexpected HTS capture of Aleppo and the cascading collapse of pro-Asad forces across western Syria. Some southern anti-Asad groups—demobilized under military pressure earlier in the conflict—remobilized as the regime collapsed. Asad fled to Russia on December 8, 2024, as HTS and southern armed groups entered Damascus.

Political and Security Dynamics

On August 21, 2025, UN Special Envoy for Syria Geir Pedersen told the UN Security Council that Syria “remains deeply fragile and the transition remains on a knife-edge.”9 The following political and security issues present the principal challenges to stability.

Transition Framework Emerges, Questions Persist on Inclusion

After a series of governorate-level consultations and a National Dialogue conference in Damascus, the interim authorities appointed members of a committee that drafted a five-year transitional constitution. In March, President Ahmed Al Sharaa signed the interim constitutional declaration and named a new transitional cabinet. The interim constitution recognizes individual rights, including freedom of belief and expression, and states a commitment to preserving the country’s territorial integrity, diversity, and social peace. The declaration vests most powers with the interim presidency and states that Arabic is the official language of the state and that Islamic law is the principal source of legislation.10 The Kurdish-led administration of northeastern Syria did not participate in the national dialogue and interim constitutional declaration drafting process.

On July 28, UN Special Envoy for Syria Geir Pedersen told the UN Security Council that “the political transition is not yet fully inclusive. And many Syrians express concern about centralized power, limited transparency, weak checks and balances, and insufficient means for genuine public consultations, participation, and scrutiny.”11 Interim authorities have announced their intention to hold indirect elections in September for 140 of 210 seats in a People’s Assembly to serve as a legislative body during the transition period. President Al Sharaa is to appoint members to the other 70 seats. The constitutional declaration may be amended by presidential proposal approved by two-thirds of the Assembly.

Arrangements for the holding of indirect elections, including participation standards for electors and administration in areas outside the interim government’s security control, have not been finalized. On August 23, a representative of the election committee said that the elections would be delayed indefinitely and seats held open for representatives from Suweida, Raqqa, and Hasakah governorates. The spokesperson said “elections are a sovereign matter that can only be conducted in areas fully under government control.”12 Pedersen told the Security Council on August 21 that any mishandling of the indirect elections or exclusionary implementation “would entrench skepticism, aggravate the forces pulling Syria apart, and impede reconciliation.”13

‘U.S. Military Presence Evolves

In December 2024, the Department of Defense reported that approximately 2,000 U.S. military personnel were then deployed in Syria. In April 2025, a Pentagon spokesperson announced the consolidation of U.S. forces in Syria and said “a deliberate and conditions-based process will bring the U.S. footprint in Syria down to less than a thousand U.S. forces in the coming months.”14 He reiterated U.S. support for efforts to combat the Islamic State (IS, aka ISIS/ISIL) in Syria, and a media report citing unnamed senior U.S. officials said that U.S. personnel would continue to assist the Kurdish-led SDF and aid SDF detention and camp management efforts. The SDF hold 9,000 IS prisoners and secure camps holding more than 30,000 people.

As of July 2025, some U.S. troops had relocated from areas with Arab-majority populations in the Euphrates River valley (see Figure 1), having closed three bases and “either dismantled and removed or handed over infrastructure to the SDF.”15 The withdrawal of U.S. forces and protection could limit the SDF’s effective control over these regions, and the U.S. military expects SDF-local tribe tensions to rise in the area.16 According to U.S. Special Envoy for Syria Ambassador Tom Barrack, the U.S. military will “eventually go to one” base in Syria.17 Turkey has sought to partner with Syria’s interim government, as well as Jordan, Iraq, and Lebanon, to establish a multilateral counter-IS mechanism that Turkey hopes could replace the U.S.-led coalition (and the U.S.-SDF partnership).18 U.S. raids in northern Syria in July and August reportedly killed individuals playing senior roles in IS operations in Syria.19

The withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria or the removal of U.S. assurances of force protection to partner forces could affect various parties’ actions, with possible implications for Syrian domestic and regional stability, counterterrorism concerns, and humanitarian needs. Sensitive considerations surround the degree of U.S. protection that might be afforded to SDF forces, who remain in discussions with Damascus over security arrangements and possible integration. Should Syrian government forces attempt to assert control over SDF-held areas by force, the United States may face calls from the SDF and other leaders in northeast Syria to intervene. Tensions between Kurds and Arabs in rural areas of northern and eastern Syria could become a flashpoint, and Turkish and interim government opposition to continued SDF control complicates matters further. U.S. Special Envoy Barrack visited Damascus on July 9 to support SDF talks with the interim government, but no progress was reported.

The United States and the Future of Northeast Syria Since 2015, the U.S. military has operated in northeast Syria and provided support to local partner forces opposed to the Islamic State group. The main U.S. partner in this effort has been the Syrian Democratic Forces, a coalition of armed groups whose leaders and strongest components are members of the People’s Protection Units (YPG), a Syrian Kurdish nationalist militia with links to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization.20

In 2017, the United States began overtly arming the YPG and other SDF elements, and by early 2019, YPG-led SDF forces backed by U.S. forces had succeeded in ending the Islamic State’s control of territory north of the Euphrates River in Syria. SDF forces took control of captured IS fighters and established security perimeters around camps for persons displaced from IS-held areas. As of July 2025, U.S. partner forces detained approximately 9,000 IS fighters and controlled camps housing approximately 31,200 individuals across northeast Syria. The SDF partners with the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). The government of Turkey consistently has objected to U.S. partnership with the YPG, characterizing the group and the wider SDF coalition as terrorists.21

In response to the YPG’s consolidation of contiguous control over much of northern Syria’s border areas by 2016, Turkey and allied Syrian militias conducted three significant military operations (in 2016, 2018, and 2019) that replaced YPG rule in some areas adjacent to Turkey with Turkish-backed Syrian forces. Turkey-Russia arrangements reached in 2019 and 2020 provided for an end to Turkish advances and joint patrols aimed at limiting the presence of the YPG and SDF in areas near the Turkish border.As the Asad government collapsed in late 2024, Russian forces implementing Turkey-Russia agreements withdrew. SDF forces moved into areas of the lower Euphrates River valley that had been under pro-Asad forces’ control, including the city of Deir-ez-Zor. HTS forces and their local partners subsequently moved to assert authority in these areas, and SDF forces withdrew north of the Euphrates River.

To the west, Turkey-backed Arab militia groups operating as part of the Syrian National Army (SNA) coalition expelled YPG and SDF forces from areas north and east of Aleppo and attempted to claim control over the Tishreen Dam and Qara Qozak bridge over the Euphrates River. Fighting continued in this region into early March 2025 before a ceasefire was reached. Periodic Turkish strikes have targeted SDF personnel east of the Euphrates, including in and around the city of Kobane.

A March 2025 agreement between the SDF and the interim government created a framework for the possible future integration of security forces and administrative entities in the northeast with the national government. The withdrawal of U.S. forces from the northeast or the removal of U.S. force protection assurances could lead the YPG and SDF, Turkey and Turkey-backed militias, and the Syrian government to change their policies and posture. Regardless of U.S. posture and preferences and the course of intra-Syrian negotiations, broader conflict could erupt and may exacerbate terrorism risks and humanitarian needs. In July 2025, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan called for SDF integration and for the YPG to “lay down its arms.”22

PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan has reportedly agreed with “top PKK operatives” that the YPG should only disarm “when an acceptable agreement is struck with the central government.”23 In August 2025, some sources indicated that SDF delays would not likely lead to direct Turkish intervention, but Turkey might indirectly support “a limited operation by the Syrian army.”24Ahmed Al Sharaa has publicly rejected any future territorial division of Syria or the use of Syrian territory by any entity to threaten Syria’s neighbors, insisting on the exclusive control of weapons by state security forces while stating his intent to resolve issues with the SDF through dialogue.25

Sharaa claimed that non-Syrian PKK militants hostile to Turkey were present in northeast Syria and objects to a possible federalist solution to questions of Kurdish autonomy. SDF Commander and YPG leader Mazloum Abdi has said the SDF is “not pursuing separatism” and “envisions itself as an integral part of a unified Syrian army, as part of a broader political solution.”26 Abdi has said that the SDF accepts state sovereignty and supports a decentralized, secular governance model. He also has said, “We hope that the coalition does not withdraw. We ask them to stay.”27

Sectarian Violence Threatens Transition, Draws Intervention

Several instances of sectarian violence involving members of minority communities, Syrian security forces, nonstate armed groups, and armed vigilantes have threatened Syria’s stability since March. Aggravating factors have included the interim government’s imperfect command and control mechanisms, extremists’ presence in some security force units and other armed groups, the proliferation of arms among the population, and volatile, conflict-fueled communal tensions. Social media dynamics, misinformation, and foreign intervention have exacerbated conditions further. Interim leaders’ rhetoric and some government actions have prioritized de-escalation and civilian protection, and leaders have promised fact-finding and accountability. Nevertheless, the government has failed to prevent widespread violations against civilians, including some undertaken by government units or government-aligned actors. Attacks on government forces and civilians perpetrated by some minority community armed groups have contributed to ongoing cycles of violence. Some Druze have called for foreign intervention, including by Israel, to ensure their protection. Others have rejected outside involvement and separatist rhetoric, while condemning government violations and failures.

Violence in Coastal Governorates

In March and April, attacks by pro-Asad groups prompted a response by security forces that devolved into attacks on some Alawite communities by some state units, government-aligned groups, and vigilantes. A UN report issued in August 2025 details eyewitness accounts of house-to-house killings, beatings, and lootings targeting Alawites, including the abuse and summary execution of Alawite men by individuals wearing military clothing without insignia.28 The report concluded that parallel hostilities were occurring between the interim government and pro-Asad armed groups at the time, and found that

there are reasonable grounds to believe that individual members of certain factions of the security forces of the interim government … as well as private individuals participating in hostilities engaged in acts that amounted to violations and international humanitarian law, including acts that may amount to war crimes, as well as serious violations of international human rights law.

The report acknowledges measures by the interim government during and since the violence to prevent further violations and “found no evidence of a governmental policy or plan to carry out such attacks.” President Sharaa personally condemned the violence and vowed to hold those responsible accountable. In the wake of the violence in western coastal areas, the interim government said it would redouble its efforts to assert unified security command over armed groups and launched a fact-finding investigation that has delivered its report to the authorities.29 That report remained unpublished in August. The UN report states that, when interviewed, residents of the coastal provinces were not aware of any actions by interim authorities to criminally investigate any individual incidents that took place during the violence.

Violence in Southern Governorates

The extent of national authorities’ control over armed groups and their commitment to civilian protection came under renewed scrutiny as sectarian violence involving members of Druze and Sunni Arab communities erupted in southern Syria in April, May, and July. Strained relationships between Druze communities and their Sunni Arab neighbors flared south of Damascus in April and May after criminal incidents and false social media reports about religiously antagonistic statements led armed groups to mobilize. In July, latent tensions between Bedouin and Druze communities in and around the predominantly Druze city of Suweida spilled over into clashes that drew in tribal fighters, security forces, and Druze militia. The violence killed nearly 1,400 combatants and civilians, displaced an estimated more than 185,000 people, and prompted military intervention by Israel, including Israeli strikes on the Ministry of Defense headquarters in Damascus.30

The UN Human Rights Office cited credible reports of “widespread violations and abuses” attributed to “members of the security forces and individuals affiliated with the interim authorities, as well as other armed elements from the area, including Druze and Bedouins.”31 Secretary of State Marco Rubio called on the interim authorities to “hold accountable and bring to justice anyone guilty of atrocities including those in their own ranks.”32 The interim government formed a committee to investigate the violence, and in September, a committee spokesman said an unspecified number of defense and interior security personnel “were detained by the interior and defense ministries to be transferred to the judiciary when the investigations are concluded to be publicly tried for the crimes they committed against Syrians.”33

As of September, a ceasefire has provided for the entry of Ministry of Interior forces into some areas of Suweida province in coordination with local Druze militia groups. Humanitarian access to Suweida remains limited, and Syrian and Israeli officials met in Paris to discuss related concerns. On August 10, the UN Security Council released a presidential statement calling on all parties to ensure humanitarian access and on the government to “to ensure credible, swift, transparent, impartial, and comprehensive investigations, in line with international standards” and to “ensure accountability and bring all perpetrators of violence to justice regardless of their affiliation.”34

Druze militias and community leaders have at times appeared to hold differing views on relations with national authorities and with Israel, with some advocating for de-escalation and cooperation and others expressing skepticism about the interim authorities’ intentions and welcoming foreign protection.35 In August 2025, leading Druze religious figures for the first time released consistent statements condemning sectarian attacks against the Druze, criticizing the interim authorities, and calling for humanitarian relief for Druze areas.36 Following pro-independence protests by some in Suweida city, Druze leader Sheikh Hikmat Al Hijri announced the alignment of several Druze militia forces under a National Guard, and has called for Suweida to be treated as a separate region.37 On August 21, UN Special Envoy Pedersen said that while violence near Suweida “has largely subsided following a ceasefire, the threat of renewed conflict is ever-present – as are the political centrifugal forces that threaten Syria’s sovereignty, unity, independence and territorial integrity.”38 The UN Security Council has called on “all states to refrain from any action or interference that may further destabilize the country.”39

Islamic State (IS) Attacks Demonstrate Enduring Threat

U.S. officials and UN experts report that IS fighters, Al Qaeda linked groups, and other extremists are seeking to exploit fragile security conditions in Syria to reinvigorate their ranks. The July 2025 monitoring report by the UN panel on Al Qaeda and the Islamic State confirms that IS fighters have seized stockpiles of heavy weapons from Asad regime stockpiles and have undertaken prison breaks freeing some of their imprisoned members and other extremists.40 The report estimates that “more than 5,000” foreign terrorist fighters remain at large in Syria.

Independent observers have catalogued more than 100 attacks attributed to the Islamic State group in eastern and central Syria in 2025, including attacks on interim government forces and SDF forces.41 Most of these attacks occurred in Deir-ez-Zor governorate in eastern Syria, but some occurred near Palmyra in central Syria and in remote areas patrolled by U.S.-backed Syrian Free Army forces based at Al Tanf in south-central Syria. A May 2025 IS statement condemned President Al Sharaa as an apostate and called on foreign fighters and others disillusioned by the interim government’s policies to reconcile and integrate with IS forces in rural areas.42

The SDF continues to detain approximately 9,000 IS prisoners, which the Department of Defense describes as “the largest concentration of ISIS fighters globally.”43 According to U.S. officials in a March 2025 report, the SDF is “fully capable of maintaining security at detention facilities while addressing external threats” but “the SDF guard force is frequently pulled away to address security demands caused by instability in the region.”44 After President Trump met President Al Sharaa in Saudi Arabia in May 2025, a U.S. official said President Trump had urged Sharaa to (among other things) “assume responsibility for ISIS detention centers in Northeast Syria.”45

SDF-secured camps at Al Hol and Roj house IS family members and other individuals displaced from the final areas retaken from IS forces in March 2019 (Figure 6). U.S. officials continue to encourage countries to repatriate their nationals from the camps. Under SDF-interim authority arrangements, some formerly IS-associated Syrian non-combatants have returned to Syrian communities. Repatriations to Iraq from Syria also have increased in 2025. SDF and UN authorities have set a goal of completing repatriations and returns by the end of 2025.

Syria and the United Nations Security Council

In 2025, the UN Security Council has called for “an inclusive, Syrian-led and Syrian-owned political process facilitated by the United Nations and based on key principles” in Security Council Resolution 2254 (2015).46 These include “commitments to Syria’s unity, independence, territorial integrity, and non-sectarian character,” “credible, inclusive and non-sectarian governance,” and, eventually, “free and fair elections” under a new constitution.47

Permanent members of the Security Council differed sharply over developments in Syria from 2011 through 2024. Differences in emphasis have persisted following Asad’s departure, though the permanent members continue to make common reference to Resolution 2254 and call for civilian protection, territorial unity, and inclusive governance.48 The United States, United Kingdom, and France have engaged with interim authorities to support the transition and have supported conditional sanctions relief for Syrian state entities. Russia seeks to preserve its military basing access in Syria and has expressed concern about attacks on minorities, the presence and actions of foreign terrorist fighters, and Israeli military operations. The People’s Republic of China has echoed these latter concerns, while highlighting the presence in Syria of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, an armed Islamist extremist group composed of ethnic Uighur and Central Asian fighters. Counterterrorism continues to provide some basis for Council consensus, but to date the Council has not revised its positions in the form of a new comprehensive resolution.

Russia and China blocked efforts in the Council to impose UN sanctions on the Syrian government and Syrian officials related to conduct during the 2011-2024 conflict, but the Council did impose targeted counterterrorism sanctions on some Syria-based groups and individuals, including HTS and Ahmed Al Sharaa.49 In a December 2024 interview, Sharaa expressed his hope that Syrians would not be unduly constrained by Asad-era UN resolutions and international sanctions, and he asserted Syrians’ collective responsibility for solving their issues internally, while also welcoming international support.50 Sharaa has argued that Asad’s departure obviates international calls for negotiation with Asad-era entities and that the interim authorities are empowered to establish conditions allowing for the return of Syrian refugees and to define and implement a transition in line with the spirit of Resolution 2254.

The UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for Syria, Geir Pedersen of Norway, has acknowledged that Resolution 2254’s specific calls for UN-facilitated negotiations “are no longer relevant,” while reiterating Security Council statements emphasizing the importance of Syria’s sovereignty, independence, unity, and territorial integrity, and calling for an inclusive and Syrian-led and Syrian-owned political process.51 Pedersen has highlighted the risks of renewed conflict posed by the unresolved status of northeast Syria and by tensions in southern Syria, and he has called for negotiated solutions and an end to military intervention by outside actors.52 In April, Pedersen criticized what he described as Israel’s “repeated and intensifying military escalations” in Syria, saying, “such actions undermine efforts to build a new Syria at peace with itself and the region, and destabilize Syria at a sensitive time.”53

Pedersen has cited Syrian and international concerns about “the inclusion of foreign fighters in the senior ranks of the new armed forces, as well as individuals associated with violations.”54 In August 2025 he expressed “grave concern over the acute threat posed by foreign terrorist fighters at large in Syria.”55

Pedersen has identified the inclusivity of a planned committee to draft a permanent constitution, the definition of mechanisms for achieving popular endorsement of such a constitution, the holding of inclusive indirect elections for an interim legislative body, and the ultimate holding of free and fair elections as critical to Syria’s transition and the principles of Resolution 2254.

Humanitarian Crises and Appeals for Assistance

UN agencies estimate that nearly 7.1 million Syrians are internally displaced (of whom 1.4 million were in organized displacement sites as of August 2025).56According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as of August 21, 4.19 million Syrians were registered as refugees in regional countries. UNHCR reports that more than 821,000 Syrians have returned to Syria through neighboring countries since December 2024, and more than 1.73 million internally displaced Syrians have returned to their homes in the same period.57 UN agencies estimate that 16.5 million Syrians are in need of some form of humanitarian or protection assistance, nearly half of whom are children.58

In March, UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator Tom Fletcher said humanitarian providers were being forced to make “brutal choices,” citing a trend of unmet appeals that caused reductions in the humanitarian response during 2024 “by more than half.”59 The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) has reported that health, education, protection, and food services have been disrupted across Syria due to limited funding of 2025 appeals and additional funding cuts, including the termination of some U.S. aid programs.60 UNOCHA officials have described the negative effects of a what they describe as a “catastrophic drop in funding” to the UN Security Council and report that global donors have funded 14% of the 2025 UN appeal for $3.2 billion through December 2025.61 The UN system has identified response priorities through December 2025 and intends to conduct a Multi-Sector Needs Assessment to support planning for 2026.62

The Asad government’s collapse obviated the obstacles and bureaucratic restrictions the former government had imposed on the delivery of humanitarian assistance to Syria. Syria’s interim security authorities have taken control of most border crossings, though large areas of northeast Syria adjacent to Turkey and Iraq are outside of their de facto control. Cross-border UN relief operations from Turkey have been extended, and goods may enter the country from functioning crossings with Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq. UN agencies report that Syrian authorities are allowing Syrian refugees to enter and exit the country. According to UN surveys, among the obstacles and challenges facing returnees are security concerns, inadequate infrastructure, and limited economic opportunity and financial liquidity in Syria, along with damage to personal property, lack of civil or legal documentation, family relocation, transportation costs, and debts incurred abroad.

U.S. Interests and Initiatives

For decades, U.S.-Syrian ties were strained and, since 1979, the United States has designated Syria as a State Sponsor of Terrorism. The former Syrian government’s hostility to Israel, its attempts to dominate neighboring Lebanon, its alignment with Russia, its partnership with Iran, its support for terrorist groups, and its development and use of weapons of mass destruction all fueled tension between the United States and Syria until the fall of Asad’s regime in late 2024. In post-Asad Syria, counterterrorism, nonproliferation, civilian protection, and regional security concerns endure and may inform future U.S. policy choices.

Congress and successive U.S. Administrations imposed and maintained a range of bilateral sanctions on Syria and targeted sanctions on entities and individuals (see “U.S. Sanctions and Syria” below). After the onset of the anti-Asad uprising in 2011 and the outbreak of conflict, the United States and European countries imposed additional, more punishing sanctions on the Syrian government and individuals and entities supporting it. The Trump Administration has pursued a policy of engagement and conditional support toward the interim government, removing many U.S. sanctions (and stating an intent to rescind Syria’s state sponsor of terrorism designation).

The duration, severity, and effects of conflict in Syria have created some actual and potential threats for U.S., European, and regional security related to terrorism, weapons proliferation, the use of chemical weapons, military intervention, drug trafficking, and mass migration. In this context, successive Administrations and Congress have prioritized the following issues:

Counterterrorism. The former Syrian government’s support for terrorism and the exploitation of Syrian territory by transnational terrorist groups to recruit, train, equip, raise funds, and plan attacks have been focal points for U.S. policymakers since before 2011. U.S. government reporting has described how Al Qaeda, the Islamic State, Hezbollah and other Iran-backed U.S.-designated terrorist groups, and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) have used Syria to further their aims, some with the active support of the Asad government.63 Syria-based members of terrorist organizations, including the Islamic State, have used Syria “to plot or inspire external terrorist operations.”64 U.S. and partner force operations ended the Islamic State’s control of populated territories in Syria in March 2019, but remnants of the group have continued to operate from remote areas in central Syria. IS fighters have attempted to break prisoners and family members out of U.S. partner-secured prisons and camps and have attacked Syrian communities and U.S. partners. In 2024, IS attacks increased in Syria relative to previous years, and, according to U.S. officials, as the Asad regime fell IS fighters “exploited the chaos to acquire some quantities of weapons and supplies from supply depots abandoned by regime forces.”65

Syria’s interim authorities, with reported intelligence support from the United States, have disrupted attempted IS attacks that could have exacerbated sectarian tensions in post-Asad Syria.66 U.S., UN, and other international officials have expressed concern about the presence in Syria of foreign terrorist fighters and the integration into Syrian security forces of foreign individuals and fighters. The interim government has appointed foreign nationals to leadership roles in its security structures, and, according to UN reporting, “many tactical-level individuals hold more extreme views” than interim government leaders.67 Interim authorities reportedly have argued that integrating anti-Asad fighters, including some foreign fighters, into national forces is preferable to dangers that might arise from their exclusion. U.S. Special Envoy for Syria Ambassador Tom Barrack reportedly said in June that the United States and Syria have reached “an understanding, with transparency” on the issue, after previous reports suggested U.S. urging of interim authorities to exclude foreign fighters.68 Some Syrian leaders and other individuals and entities active in Syria remain subject to U.S. and UN terrorism sanctions (see “U.S. Sanctions and Syria” below).

Foreign Military Access and Basing. Since 2011, the presence and operations in Syria of foreign military forces from Russia, Iran, Turkey, Israel, and the United States and its partners have reflected the differing priorities and goals of outside actors in the country. U.S. policymakers may consider whether or how the continued operations in Syria of U.S. and coalition forces, Turkish forces, and Israeli forces affect U.S. interests. U.S. officials also may monitor and seek to shape the policies of Syrian interim authorities toward foreign military forces, including U.S. forces, Russian forces invited to Syria by the Asad government, and Israeli forces operating in and beyond the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force zone in the Golan Heights established in the 1974 Israel-Syria Disengagement Agreement. Syria’s interim authorities say they seek to establish normal diplomatic and security relationships with foreign countries—including their former Russian and Iranian adversaries—on the basis of mutual respect for sovereignty and noninterference. Syrian and Israeli officials met in Paris in August 2025 to discuss deconfliction and de-escalation following Israeli airstrikes on Syrian forces in July, including in Damascus, and Israeli operations in the Golan region and near the Lebanon-Israel-Syria tri-border. In a February 2025 interview, Ahmed Al Sharaa said “any military presence should be with the agreement of the host state.”69

Weapons of Mass Destruction. The Asad government’s domestic use of chemical weapons against its armed opponents and civilians drew international condemnation and motivated U.S. military strikes in 2017 and 2018. In December 2024, the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) said “significant concerns persist regarding the accuracy and completeness” of the former government’s declarations to the agency, “as well as the fate of substantial quantities of unaccounted-for chemical weapons.”70 Outstanding issues of concern reported to the OPCW Secretariat prior to Asad’s ouster “involved large quantities of potentially undeclared or unverified chemical warfare agents and chemical munitions.”71

In March 2025, interim Foreign Minister Asaad Al Shaibani participated in an OPCW meeting and stated the interim government’s commitment “to destroy any remains of the chemical weapons programme developed under the Assad regime, to put an end to this painful legacy, to bring justice to victims, and to ensure that the compliance with international law is a solid one.”72 The OPCW since has deployed Declaration Assessment Team and Office of Special Missions personnel to Syria with the support of the interim government. The personnel have visited declared and suspected chemical weapons program locations and have reported their findings to the OPCW and the interim government.

The interim authorities have informed the OPCW that they lack the information and expertise to definitively identify and declare all chemical weapons related locations and materials, and the OPCW has estimated that experts will “need to visit and assess more than 100 additional locations across the Syrian Arab Republic, including military facilities, airfields, and research centres, all of which may be in varied, and hazardous, states of disarray, damage, or destruction.”73The OPCW estimates that additional donor country contributions of 33.1 million euros will be required for Syria-related activities through 2027.

Conventional Weapons and Regional Security. The influx of weapons to Syria and their wide distribution in-country since 2011 present enduring threats to Syria’s internal security and to the security of Syria’s neighbors. Criminal groups, extremist organizations, and non-state armed groups, including some aligned with Iran and Turkey, have benefitted from the proliferation of small arms and military weapons during the conflict. In addition, unexploded ordnance, mines, and other explosive remnants of war pose risks to Syrian civilians and international actors across Syria. Interim authorities’ ability and willingness to assert control over weapons stockpiles associated with the former government may be limited or vary in different areas. Israel has acted to destroy advanced conventional weapons and military air defense and air domain awareness systems across Syria since December 2024, citing potential risks to Israel’s security.74

Drug Trafficking. The Asad government enabled and profited from the production and smuggling of drugs across the Middle East, especially the drug captagon.75 Congress sought to limit the Asad government’s ability to profit from the captagon trade. In the 117th Congress, the Countering Assad’s Proliferation Trafficking and Garnering of Narcotics Act (H.R. 6265, also known as the CAPTAGON Act) was introduced by Representative French Hill in December 2021, passed by the House in September 2022, and incorporated into the FY2023 NDAA (Section 1238 of P.L. 117-263). It has required the development and submission to Congress of an interagency plan to disrupt captagon trafficking and build regional counterdrug capacity. Interim authorities have pledged to dismantle captagon production and smuggling networks and cooperate with regional countries to halt the flow of the drug across Syria’s borders. Arrests of criminals, including drug traffickers, are being publicized by interim authorities. Criminal networks’ loss of captagon trade revenues may add to economic pressures in some areas of Syria.

Human Rights and Syrian Minorities. The Asad government’s use of military force to repress demonstrations led many Syrians, the United States, and other countries in 2011 to call for Asad’s departure. The Asad government’s subsequent use of torture and its mass execution of prisoners continue to drive Syrian and international calls for accountability. Interim authorities have made statements calling for inclusive governance and respect for religious tolerance, and U.S. and other international officials have called on interim Syrian leaders to fulfill these commitments. U.S. officials have condemned attacks on minority communities, including by members of or forces associated with the interim government (see “Political and Security Dynamics” above). Some members of minority communities in northeast and southern Syria have expressed support for decentralized governance and appear to remain skeptical of interim authorities’ intentions.

The State Department in 2023 designated HTS as an entity of particular concern pursuant to the Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act (P.L. 114-281), and reported in 2025 that “armed terrorist groups, including Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, reportedly carried out arbitrary detentions and subjected some detainees to torture” during 2024.76 The State Department’s annual human rights report on conditions in Syria during 2024 cites UN Commission of Inquiry for Syria reporting and other human rights organizations’ reporting alleging the involvement of SDF, HTS, and Turkey-backed SNA forces in a range of human rights abuses and violations. The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom recommended in its 2025 annual report that HTS be redesignated.

U.S. Diplomacy

President Donald Trump’s May 2025 meeting in Saudi Arabia with Ahmed Al Sharaa and President Trump’s announcement of his intent to rescind U.S. sanctions on Syria signaled a new approach in U.S. policy toward Syria. High level U.S. engagement and substantial sanctions relief have been presented as a conditional opportunity for Syrians and transitional leaders to rebuild and reorganize while interim authorities demonstrating their intentions toward ethnic and religious minority groups, terrorist threats, and Syria’s neighbors. The Trump Administration’s engagement builds on initial contacts made and steps taken by the previous Administration in the wake of Asad’s departure.77 In 2025, U.S. Special Envoy for Syria Ambassador Tom Barrack and some Members of Congress have visited Syria.

In May, the Trump Administration took steps to waive and relieve some U.S. sanctions on Syria and in June and July the Administration rescinded and revised executive orders providing for many U.S. sanctions on Syria and revoked the designation of HTS as a Foreign Terrorist Organization. As of September, the group, Sharaa, and Interior Minister Anas Khattab remain listed as terrorist entities pursuant to Executive Order 13224, and remain subject to UN sanctions.

The United States suspended operations at the U.S. Embassy in Damascus in 2012; the Czech Republic serves as the U.S. protecting power in Syria. On May 29, Ambassador Barrack and other officials raised the U.S. flag at the U.S. diplomatic residence in Damascus for the first time since 2012.78 The Trump Administration has not announced any plan to return U.S. personnel to Syria on an enduring basis. In March 2014, the State Department suspended the operations of the Syrian embassy in Washington, DC, and those of Syrian consulates in Michigan and Texas, and expelled Syrian staff.

U.S. Military Operations in Syria and U.S. Partner Forces

U.S. forces have operated in Syria since 2014 pursuant to the 2001 and 2002 Authorizations for Use of Military Force (AUMF). U.S. operations in Syria as part of Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) seek the enduring defeat of the Islamic State. As of December 2024, an estimated 2,000 U.S. military personnel reportedly were present in eastern and southern Syria, conducting counterterrorism missions against IS remnants and supporting Syrian partner forces. U.S. forces have conducted dozens of airstrikes and multiple operations against IS targets in Syria since Asad’s ouster, and have targeted Al Qaeda affiliates in northwest Syria in 2025.

Most U.S. forces in Syria have been deployed in the northeast in support of the SDF. U.S. troops also have supported the Syrian Free Army (SFA) near Al Tanf in a former deconfliction zone in southern Syria, along a transit route between Iraq and Syria once used by both IS fighters and by Iran and Iran-backed militias. In 2025, U.S. forces have continued to provide support to the SFA following that group’s integration with the Syrian interim government under its 70th Division.

In April 2025, a Pentagon spokesperson announced the consolidation of U.S. forces and said “a deliberate and conditions-based process will bring the U.S. footprint in Syria down to less than a thousand U.S. forces in the coming months.”79 By July 2025, some U.S. troops had relocated from areas with Arab-majority populations in the Euphrates River valley (see Figure 1), having closed three bases and “either dismantled and removed or handed over infrastructure to the SDF.”80 Ambassador Barrack has said the U.S. military will “eventually go to one” base in Syria.81

Since 2015, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) has conducted periodic military strikes in Syria outside the framework of OIR, including on targets linked to Al Qaeda, Syrian government chemical weapons-related targets, and Iran-backed militias—some of which used Syria-based facilities to monitor and target U.S. forces. From October 2023 to November 2024, the U.S. military conducted strikes on facilities in eastern Syria associated with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and affiliated militias in response to attacks by Iran-backed militias on U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq. In 2024, U.S. officials reported force protection concerns linked to terrorist groups, Russia and Syrian government forces, and Iran-backed groups.

Syria Train and Equip Program FY2025 Funding and FY2026 Legislation

The Syria Train and Equip program, authorized by Congress since 2014 and funded via the Defense Department Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund (CTEF), seeks to sustain the defeat of the Islamic State in Syria by enabling Syrian partner forces in the SDF and the SFA. President Joe Biden requested and Congress appropriated $147.9 million in FY2025 CTEF funds for Syria programs available through September 2026. The FY2025 National Defense Authorization Act extended authorities for U.S. train and equip programs in Syria through December 2025.

The Trump Administration’s FY2026 defense appropriations request seeks nearly $130 million for CTEF programs in Syria, with funds remaining available through September 2027. Program costs include training and equipping, logistical support, stipends, repair, and sustainment investments to support paramilitary, internal security, and detention personnel.

The House and Senate reported versions of the FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA, H.R. 3838/S. 2296/S.Amdt. 3748) would reauthorize train and equip programs in Syria at the requested funding level through December 2026. The Senate-reported version and amendment in the nature of a substitute (ANS, S.Amdt. 3748) include a provision that would prohibit the obligation or expenditure of funds authorized to be appropriated by the act “to reduce the number of, or consolidate, bases of the United States Armed Forces located in Syria” until 15 days after a certification is submitted providing assessments and information on U.S. posture and plans to continue to achieve counterterrorism objectives. The Senate-reported version and ANS also include a provision directing the Secretary of Defense in consultation with the Secretary of State to take measures to support the defenses and internal security of the Al Hol and Roj camps and to provide annual reporting to Congress on related matters. The report accompanying the House version (H.Rept. 119-231) would require a briefing to the House Committee on Armed Services “not later than February 15, 2026, on the progress, challenges, and outlook for potential U.S. defense partnership with the new Syrian government.”

The House-passed and Senate-reported defense appropriations bills for FY2026 (H.R. 4016/S. 2572) would appropriate funds for Syria at the requested level. The Senate-reported bill would rescind $5 million in FY2025 appropriations from the CTEF account. The report accompanying the House version (H.Rept. 119-162) would direct the Secretary of Defense to provide a briefing within 60 days of enactment to “assess the integration of the Syrian Democratic Forces into the new Syrian government security force and evaluate progress made under the Al Hol Action Plan.” (see below)

U.S. Support for IS Prisoner Detention and Camp Management

Successive Administrations have used Department of Defense and State Department programs to address challenges posed by the continued detention in Syria by U.S. partner forces of thousands of IS fighters and the presence of tens of thousands of formerly IS-associated individuals in U.S. partner-secured camps. Since 2019, transferring prisoners and returning camp residents to their home countries and communities has been slowed by other governments’ fears about radicalization and by the uncertain security conditions prevailing in Syria. Ensuring the continued detention of IS fighters has been a high priority for successive Administrations, and Congress has directed specific resources and outlined requirements for U.S.-funded efforts related to humane detention and security practices. U.S. officials and partner forces considered and chose not to pursue plans to construct new purpose-built facilities to detain IS prisoners.82 Instead, upgrades to existing facilities have been undertaken with U.S. support, starting with those assessed to have the highest risk. U.S. officials reported in July 2025 that all SDF-run prisons have received basic upgrades, though longer-term upgrades “have not yet resulted in a marked increase in security.”83

The Departments of Defense and State have funded various training programs for U.S. partner force personnel focused on securing prisons and camps in northeast Syria. Some partner force personnel have received training in compliance with international humanitarian law and detainee treatment. In July, CJTF-OIR reported that because of competing demands SDF forces are “not consistently available to receive training.”84 CJTF-OIR further reported that “the lack of a formal training program for the SDF guard force… limits Coalition visibility into any deeper problems that might exist.”

The FY2024 Further Consolidated Appropriations Act directed that not less than $25 million in ESF monies be made available to implement the “U.S. Government Al-Hol Action Plan,” which has sought to improve conditions in the camp and support reintegration. As of June 2025, lead inspector general reporting to Congress stated that all USAID programming supporting the plan had been terminated, but that State Department programs for camp management, coordination, and child education and protection were ongoing.85

Speaking to the UN Security Council in February, a U.S. official said the United States supports a ceasefire in northern Syria that will “enable our local partners to focus on combatting ISIS and maintain security of detention facilities and displaced persons camps.”86 The official also said that ongoing U.S. assistance for the operations of the prisons and camps in northeastern Syria “cannot last forever” and “cannot remain a direct U.S. financial responsibility,” urging “countries to expeditiously repatriate their displaced and detained nationals who remain in the region.”87

Of the funds appropriated for CTEF programs in FY2025, $15 million was directed to infrastructure repair and renovation. The Administration’s FY2026 request seeks $1.6 million for these purposes. The Senate Appropriations Committee report S.Rept. 119-52 accompanying its version of the FY2026 defense appropriations bill (S. 2572) would direct the Department of Defense to report to the committee 30 days prior to obligating funds for construction activities, states that the committee “prioritizes detention facilities repair and construction ahead of any other construction activity,” and would direct the Secretary of Defense “to engage with the SDF on ensuring that detainees are afforded all protections due under the Geneva Conventions.” The Senate-reported version of the FY2026 NDAA (S. 2296) and ANS (S.Amdt. 3748) include a provision directing the Secretary of Defense in consultation with the Secretary of State to take measures to support the defenses and internal security of the Al Hol and Roj camps and to provide annual reporting to Congress on related matters.

U.S. Stabilization and Foreign Assistance

The future of U.S. stabilization and foreign assistance programs in Syria is uncertain in light of developments in Syria and changes following the Trump Administration’s review of U.S. foreign assistance activities and implementation of agency reorganization plans and staff relocations. Through 2024, U.S. assistance supported stabilization programs in northeast Syria, funded engagement with civil society and training for local governance and security entities in areas outside of the Asad government’s control, and helped meet housing, services, reintegration, and repatriation needs at the Al Hol and Roj camps.

According to lead inspector general reporting to Congress, as of June 30, all USAID stabilization programming in Syria has been terminated. Some State Department stabilization programs have been continued. Others have been terminated.88 USAID humanitarian assistance activities were paused in early 2025. Some were restarted and others were terminated. Lead inspector general reporting to Congress cites USAID officials as reporting that, “as a result, many partners paused operations and the delivery of lifesaving humanitarian assistance, and in some cases terminated staff and closed offices.”89 USAID officials further reported that as of June 2025, “all USAID implementers were partially operational due to lack of payment,” and termination of third-party monitoring contracts was “increasing the risk of waste, fraud, and abuse—especially in conflict-affected areas, where there is a heightened potential for diversion of funds.”90

The Trump Administration has provided congressional committees of jurisdiction with updated lists of foreign assistance programs in Syria that it has terminated and preserved following its global review of U.S. foreign assistance. Changing conditions, opportunities, and risks in Syria may prompt further changes to U.S. assistance plans.

The Trump Administration’s FY2026 budget request for foreign assistance does not include a specific amount for Syria programs, but, consistent with the prior Administration’s requests, does seek authority notwithstanding other provisions of law to provide “non-lethal stabilization assistance for Syria, including for emergency medical and rescue response and chemical weapons investigations.”91 The House Appropriations Committee-reported version of the National Security, Department of State, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2026 (H.R. 4779) includes this language, and would make funds available for assistance for ethnic and religious minorities in Syria.

U.S. Sanctions and Syria

From 1979 to 2024, the United States placed a broad array of sanctions on the government of Syria, Syrian entities and individuals, and third parties supporting certain Syrian government activities. The United States also imposed targeted sanctions on terrorist groups active in Syria and associated individuals. Successive Administrations and Congresses imposed and maintained these sanctions as a means of raising the costs to Syrian leaders of a number of policies they deemed hostile to U.S. national security, foreign policy, and economic interests. Specific sanctions actions were taken by different Administrations to address the Syrian government’s support for terrorism, its trade in weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missile technologies, its interference in neighboring Lebanon, and its conduct during the country’s 2011-2024 conflict.

Sanctions Relief and Remaining Authorities

In January 2025, the Biden Administration issued a general license to allow for certain transactions in Syria through July 6, 2025, to include transactions with the government of Syria, transactions related to noncommercial personal remittances, and transactions in support of the sale, supply, storage, or donation of energy, including petroleum, petroleum products, natural gas, and electricity. President Biden also issued Executive Order 14142, amending Executive Order 13894 (2019)92 to remove specific references to the government of Turkey and preserving provisions allowing the potential imposition of financial and travel sanctions on individuals determined by the President to “threaten the peace, security, stability, or territorial integrity of Syria;” or be involved in “the commission of serious human rights abuse” related to Syria.

On May 13, 2025, President Trump said during a visit to Saudi Arabia that his Administration is “currently exploring normalizing relations with Syria’s new government,” and said he would “be ordering the cessation of sanctions against Syria in order to give them a chance at greatness.”93 The Administration subsequently provided exemptive relief for sanctions on the Commercial Bank of Syria, issued a 180-day waiver of sanctions in the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2019 (“Caesar Act,” 22 U.S.C. §8791 note),94 and issued a general license (GL 25) that authorized certain transactions with Syria and designated individuals that would otherwise be prohibited under sanctions regulations.95

On June 30, President Trump issued Executive Order 14312, eliminating or waiving many Asad-era sanctions on the government of Syria, while amending Executive Order 13894 (2019) again to maintain sanctions on Asad-associated entities and refine mechanisms for possibly imposing future sanctions on entities determined to be disrupting Syria’s transition, violating human rights, or threatening Syria’s stability or territorial integrity. The order directs the Secretary of State to “take all appropriate action” with respect to Syria’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism96 and the designation of Jabhat Al Nusra/Hay’at Tahrir al Sham as a Foreign Terrorist Organization and a Specially Designated Global Terrorist entity. It also directs the Secretary of State to review President Sharaa’s individual designation. On July 8, Secretary Rubio’s determination revoking the FTO designation of HTS was published.97

On August 26, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) published a final rule removing the Syrian Sanctions Regulations (31 CFR Part 542) from the Code of Federal Regulations, consistent with Executive Order 14312. According to the final rule, “OFAC intends, in a separate rulemaking, to amend 31 CFR part 569 to rename it the Promoting Accountability for Assad and Regional Stabilization Sanctions Regulations and to incorporate E.O. 13894, as further amended, and other relevant authorities. The Administration’s July 2025 amendment of EO13894 (2019) preserves a framework for the potential imposition of sanctions on actors in Syria for “(1) actions or policies that further threaten the peace, security, stability, or territorial integrity of Syria; or (2) the commission of serious human rights abuse.”98

Legislation providing for some specific U.S. sanctions on the Syrian government and entities in Syria has not been amended or rescinded since December 2024, although there is debate in Congress over several related legislative proposals (see “Legislation and Hearings in the 119th Congress” below).99 Some other terrorism, chemical and biological weapons and missile proliferation sanctions, human rights-related sanctions (addressing trafficking in persons and child soldiers), and drug trafficking (captagon) statutory sanctions apply. If the President or his designees act to further waive or permanently rescind the application of sanctions on Syria, such as Syria’s State Sponsors of Terrorism designation, then specific notification and certification requirements to Congress under law may apply.

In the interim, the continuing application of the Caesar Act and Executive Order 13894, as amended, provide a basis for the U.S. government to reimpose some sanctions on Syrian actors if the President and his Administration determine that doing so is in U.S. interests. In May 2025, Secretary Rubio said “the President has made clear his expectation that relief will be followed by prompt action by the Syrian government on important policy priorities.”100 That month, the Department of the Treasury said, “U.S. sanctions relief has been extended to the new Syrian government with the understanding that the country will not offer a safe haven for terrorist organizations and will ensure the security of its religious and ethnic minorities. The U.S. will continue monitoring Syria’s progress and developments on the ground.”101

Earlier in May, the State Department had announced that Secretary of State Rubio recertified Syria as a “‘not fully cooperating country’ (NFCC) under section 40A of the Arms Export Control Act.” The Government of Syria is consequently denied trade with the United States in defense articles and defense services under section 40A of the Arms Export Control Act.102

U.S. Targeted Terrorism Sanctions

In May 2018, the executive branch added Hayat Tahrir al Sham as an alias of the Nusrah Front, which until July 2025 was designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization under Section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act. As of September, HTS remains a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) entity under Executive Order 13224. The executive branch designated Sharaa as an SDGT pursuant to Executive Order 13224 in 2013; as of September, he remains so designated, as does interim Interior Minister Anas Khattab. Sharaa has described U.S. terrorism related sanctions on him, HTS, and other former HTS figures as no longer warranted in light of subsequent counterterrorism actions and commitments and their post-Asad decision to disband armed groups, including HTS. The executive branch retains authority to amend or rescind SDGT designations under current law.

U.S. Targeted Terrorism Sanctions

In May 2018, the executive branch added Hayat Tahrir al Sham as an alias of the Nusrah Front, which until July 2025 was designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization under Section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act. As of September, HTS remains a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) entity under Executive Order 13224. The executive branch designated Sharaa as an SDGT pursuant to Executive Order 13224 in 2013; as of September, he remains so designated, as does interim Interior Minister Anas Khattab. Sharaa has described U.S. terrorism related sanctions on him, HTS, and other former HTS figures as no longer warranted in light of subsequent counterterrorism actions and commitments and their post-Asad decision to disband armed groups, including HTS. The executive branch retains authority to amend or rescind SDGT designations under current law.

European Union (EU) Sanctions