ROME — On September 7, Pope Leo XIV is set to confer sainthood on Carlo Acutis, a teenager from Italy hailed as “God’s influencer” for his pioneering use of the internet to publicize what are known as “bleeding host” miracles.

Acutis, who is being sainted for his exemplary life and for using his computer skills to spread his faith, will become the Roman Catholic Church’s first millennial saint in Leo’s first canonization ceremony. The ceremony will take place at St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.

But behind the celebration lies a troubling legacy: The very miracles Acutis promoted online are rooted in centuries-old antisemitic myths that have fueled hatred and violence against Jewish communities.

Leading Jews and Catholics have criticized Rome for overlooking the antisemitic motifs tied to some of these miracles. Recently, German antisemitism commissioner Felix Klein criticized the Church for ignoring the anti-Jewish aspects of the miracles highlighted by Acutis, which historically led to “the murder of Jews.”

Acutis died of leukemia in 2006 at the age of 15, after using the coding skills he learned in school to create a website cataloging accounts of consecrated communion wafers said to bleed or transform into flesh.

Although Acutis avoided explicit mention of Jews in these narratives, referring instead to “desecrators” or “malefactors,” the historical sources he drew from — including Church records and devotional literature — often identify the perpetrators as Jewish.

Carlo Acutis, born May 3, 1991, London, England; died October 12, 2006, Monza, Italy. (Maurizio Maule/IPA/Sipa USA, via Reuters)

The miracles Acutis showcased were part of a larger online exhibition he made that also included Marian apparitions and visions of angels and demons. But among the most prominent eucharistic stories, many portray Jews as Christ-killers who desecrate the host — believed by Catholics to be the real body and blood of Jesus — by stabbing, mutilating, or boiling it.

Antonia Salzano, mother of Carlo Acutis, poses in front of a portrait of her son, in Assisi, on April 4, 2025. (Photo by Tiziana FABI / AFP)

These stories helped embed antisemitic tropes in Christian imagination, inspiring art, relics, processions, and feast days. Executions, pogroms, or mass expulsions of Jews often followed the allegations of sacrilege.

“I only checked a couple of the host desecration accounts on Acutis’s site, and they sanitize what is a history of anti-Jewish mythology that resulted in many Jewish deaths,” said Prof. David Kertzer, author of “The Popes Against the Jews: The Vatican’s Role in the Rise of Modern Anti-Semitism.”

“The author, presumably the boy to be canonized, accomplished this by deleting the central element motivating these cases: the charge that nefarious Jews were surreptitiously defiling the Eucharist out of hatred for Christianity,” Kertzer, a professor of social science, anthropology and Italian studies at Brown University, told The Times of Israel.

Kertzer lamented that it was “very unfortunate on the 60th anniversary of Nostra Aetate for the Vatican to be recycling a history that had in fact finally been repressed by the Church.”

The Times of Israel contacted Cardinal Marcello Semeraro, prefect of the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints, as well as the Holy See Press Office and the Association of the Friends of Carlo Acutis for comment, but did not receive a response.

Ahead of Acutis’s canonization, on August 15, an 11-foot-tall bronze sculpture of the millennial saint by Canadian sculptor Timothy Schmalz was unveiled next to Acutis’s tomb in Assisi.

A template is set

The archetypal miracle of Jews desecrating the consecrated wafer recorded on Acutis’s website occurred in Paris in 1290. Acutis claims to have obtained information from authoritative sources, including French Archbishop Jean Rupp’s “Histoire de L’Église de Paris.”

But while Rupp specifically identifies the desecrator Jonathas as a Jew, Acutis describes Jonathas as “a non-believer” who “hated the Catholic Faith.”

Historian Susan Einbinder, in her 2002 book “Beautiful Death: Jewish Poetry and Martyrdom in Medieval France,” identifies Jonathas as a Jewish moneylender who obtains the host on Easter Sunday through a client whose garment he holds in pledge.

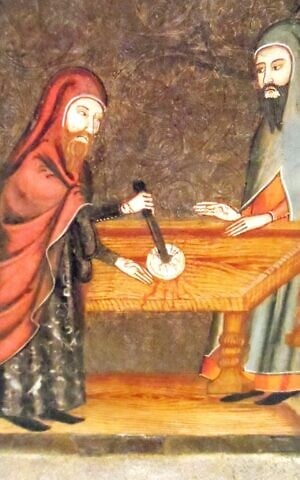

A 16th-century painting showing the alleged desecration of hosts by Jews in Passau in 1477. (Wolfgang Sauber/ Wikimedia commons)

Mimicking aspects of Christ’s crucifixion, Jonathas stabs the host, nails it, burns it, hoists it on a lance, and flings it into boiling water. The host bleeds profusely. Finally, it jumps into a vessel carried by a Catholic woman who has just entered Jonathas’s house. After the Jew is exposed, he refuses to convert and is burned alive. His wife and children repent and are baptized.

“Although there is evidence that host libels were in circulation before 1290, the Paris 1290 incident set the standard against which subsequent desecration narratives took form,” writes Einbinder. The libel inspires “a wave of ‘copycat’ accusations” against Jews over decades.

No love lost

Several miracles recorded by Acutis echo the antisemitic motif of Jewish witches stealing hosts to make love potions. In a 1273 miracle, Richiarella, a Catholic woman from Lanciano, Italy, consulted a witch to regain her husband Giacomo Stasio’s affection.

A medieval painting of host desecration by Jews, from the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona. (Wikimedia commons)

The sorceress instructed Richiarella to obtain a host, fry it in a pan, and add it to her husband’s food. The host turned into flesh, which Richiarella buried in their stable, causing the family donkey to genuflect whenever it entered the barn.

Lanciano’s local historian, Maurizio Angelucci, identifies the witch as a Jewess who was said to have obtained the host for an erotic potion. “That explains why everyone born in Lanciano is nicknamed by the curious dialectal word ‘Frjiacriste’ [‘to fry Christ’],” he writes in a 2019 history of the area.

A variation is the 1247 miracle of Santarem, Portugal, where a jealous woman consulted a sorceress who asked her to steal a host to make a love potion. The host bled when hidden in a linen kerchief.

Acutis also catalogs an 11th-century miracle in Trani, Italy, where a “non-Christian woman” stole a host and fried it in oil. The blood flowed onto the floor and out the door.

Bob and Penny Lord’s Catholic devotional book “Miracles of the Eucharist II” identifies the witch as “a Jewish woman who had an overpowering hatred for the Church.” She was executed but converted before her death, and her house was turned into a shrine.

The ‘miracles’ continue

Acutis also recorded another famous miracle, set in Brussels. He described the “desecrators” as friends “filled with hatred of things Catholic.” A “rich merchant from Enghien” colluded with a “young man from Louvain” to steal hosts and slash them on Good Friday, 1370. The hosts bled, and the terrified “desecrators” entrusted them to a Catholic merchant.

Amelia Simone, 18, a student from the United States, stands in front of the entrance of the Santa Maria Maggiore Church where the body of the 15-year-old Italian boy Carlo Acutis, who died in 2006 and was beatified in 2020, is kept, in Assisi, Italy, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

Historian Miri Rubin identifies the merchant as Jonathan of Enghien, a “prominent Jew” and “substantial financier and community leader,” in her 1999 book “Gentile Tales: The Narrative Assault on Late Medieval Jews.” In the original narrative, Jonathan and his Jewish friends took the hosts to the synagogue, pierced them with knives, and then Jonathan was killed two weeks later. Six Jews were burned at the stake, members of Jewish communities were arrested, properties confiscated, and Jews were banished from Brussels.

Luc Duerloo, historian at the University of Antwerp, concluded in a 2000 monograph that the parish priest of the chapel, Fr. Pierre Van Heede, was responsible for slandering the Jews and transforming the alleged desecration into a miracle.

A faithful waves a flag with Carlo Acutis, the 15-year-old Italian boy who died in 2006 of leukemia and beatified in 2020, at the funeral of Pope Francis in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican, April 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Acutis recounted a similar miracle from Poznań, Poland, in 1399, where “profaners with an intense hatred for the Christian faith” bribed a Catholic maid to steal three hosts. The hosts bled when mutilated with a “hole-puncher,” were dumped in a swamp, and then flew and appeared to a shepherd boy.

Historian Magda Teter, in her 2011 book “Sinners on Trial: Jews and Sacrilege After the Reformation,” shows how the Carmelite monk Tomasz Rerus embellished the narrative in a 1583 pamphlet. According to Rerus, Jewish rabbis attempt to conceal the crime, but the blood covers their faces and the cellar walls, refusing to wash off. The magistrate punishes the Jews and their Catholic accomplice.

In the case of the 1430 host miracle of Dijon, Acutis describes an “ignorant” woman who uses a knife to remove the host from a monstrance she bought from a second-hand dealer, causing it to bleed. However, the Metropolitan Museum and other historians preserve the original version where a Jew stabs the host.

Shared concerns over antisemitic mythology

Canonization procedures require rigorous investigation, recognition of heroic virtue, and proof of miracles. “Over centuries, it has become common theological opinion that the pope is infallible when solemnly canonizing saints,” writes Donald Prudlo in “Certain Sainthood: Canonization and the Origins of Papal Infallibility in the Medieval Church.”

Pictures of Carlo Acutis are printed on souvenirs in a shop in Assisi where Acutis’s body is on display, on April 3, 2025. Acutis, the world’s first millennial saint who died in 2006 aged 15, will be canonized by Pope Francis on April 27, 2025, in The Vatican. (Photo by Tiziana FABI / AFP)

“It is troubling that miracles rooted in antisemitic blood libels are being lauded without acknowledging their context. These narratives had catastrophic consequences for European Jewry, and their legacy endures in modern blood libels today,” a Campaign Against Antisemitism spokesperson told The Times of Israel.

However, Andrea Grillo, a professor at the Pontifical Athenaeum of St. Anselm in Rome, said it would be “unfair to attribute anti-Jewish intentions to Acutis, since he was not even aware of the anti-Jewish roots and consequences of some of the so-called Eucharistic miracles.”

Grillo, whose article “Young Carlo Acutis and Eucharistic Rudeness” criticizes Acutis’s eucharistic theology as “so outdated, so burdensome, so obsessive, [and] so focused on the inessential,” acknowledged that the treatment of episodes such as the “miracle of Brussels… which objectively present an anti-Jewish component, was very superficial.”

“This cannot be overcome by simply omitting the identity of those implicated in the incident,” Grillo elaborated. “This is a serious issue that must be brought to the public’s attention and would have deserved greater scrutiny, including more informed discernment of the ‘miracle cases’ included in the exhibition. The superficiality that can be forgiven in a 14-year-old boy is unacceptable in adults who reconstructed his life and works.”

Simone Rizkallah, director of Philos Catholic, an organization promoting a Catholic understanding of the Church’s Hebrew roots, told The Times of Israel that “acknowledging the painful legacy of certain Eucharistic miracle claims rather than glossing over them allows us to deepen our witness to the truth and beauty of our faith.”