In Canada, we like to think of ourselves as progressive and inclusive and, relative to other nations today, we most likely are. That hasn’t always been true; our history is littered with heinous events and policies that persecuted the Indigenous peoples of this country. One of the main efforts to erase Indigenous identity and culture is known as the Sixties Scoop, an approximately four-decade period in the late Twentieth Century when government policy allowed child welfare services to ‘scoop’ children up and out of their families for the express purpose of having non-Indigenous families adopt them. We, as a nation, are still grappling with the fallout of this –and other heinous institutions like the Residential School System– on a larger cultural level. However, it can be easy to forget the very real people affected by these atrocious systems—the insidious, pervasive nature of the harm caused. Individuals, families, and whole communities are all still dealing with the scars of this state-perpetrated abuse.

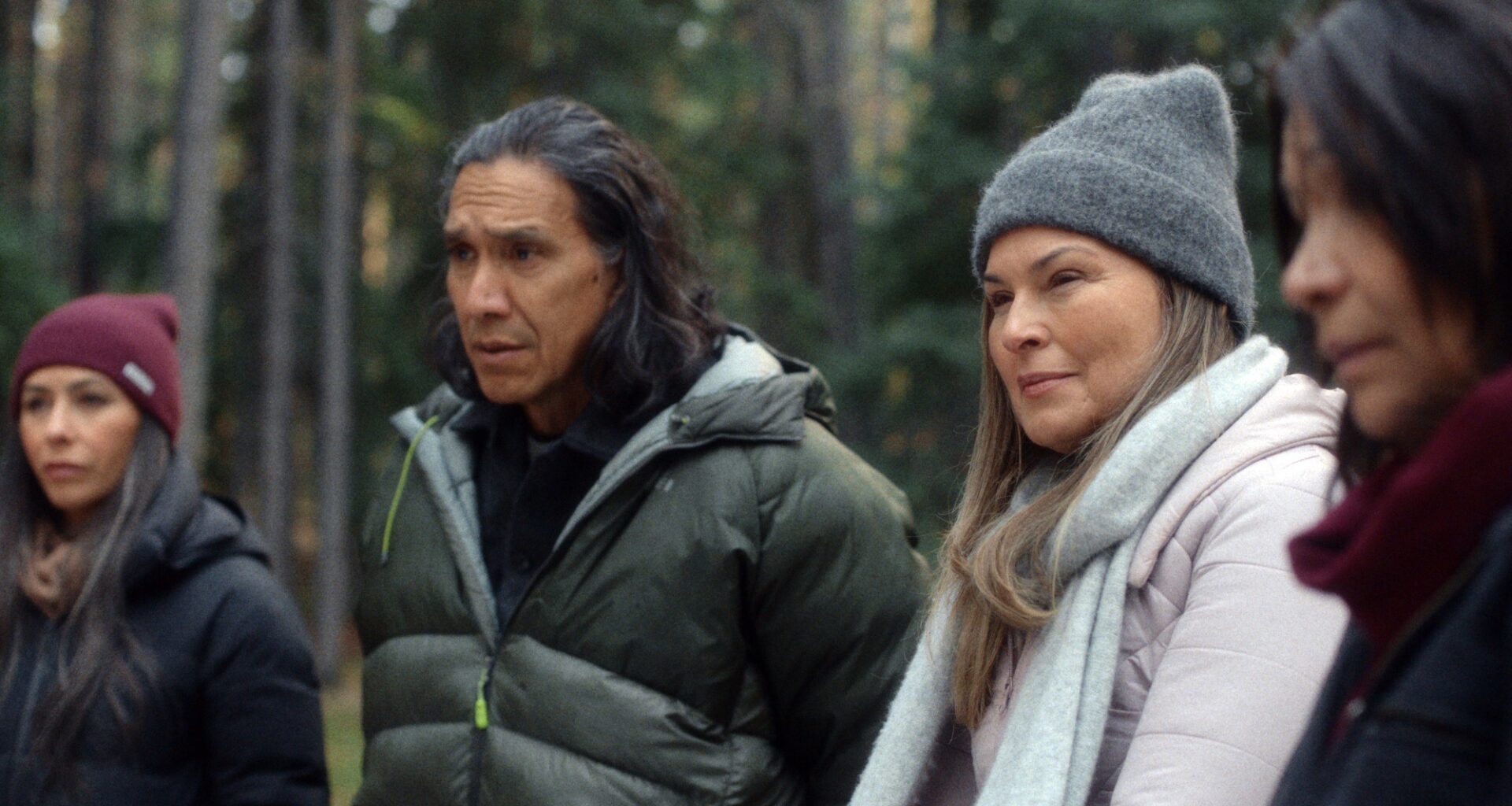

Meadowlarks, co-written and directed by Tasha Hubbard, follows the siblings from one such family. Five Cree siblings were forcibly separated from their mother, and four of them (played by Michael Greyeyes, Carmen Moore, Alex Rice, and Michelle Thrush) agree to come together in Banff, nearly fifty years later, in an attempt to reconnect. It is a thoughtful film, featuring slow and affecting dialogue about lost childhoods, the effects of being denied one’s own culture, and being othered not just by the powers that be, but also by the families they were placed with.

All four of still feel the pull of their family, of each other, and the tangibility of the time they’ve lost–with each other and with their community–is heartbreaking to behold. Whether adopted as a teenager or as a baby, each has felt disconnected to their lives in different ways. Each actor gets a moment to shine in the telling of their individual life experiences, and each is, in their own way, a story of isolation and loneliness. Whether it’s the story of the sibling who spent time on the street and is now purposefully avoidant of alcohol, or the sibling who was adopted into a seemingly nice life in Europe, each of them recognizes a hole in themselves that only the others can replace.

In many ways, Meadowlarks feels like a play. There are a few locations, and lots of dialogue, but that is perhaps the point. These are stories that need to be shared, that we need to hear, based on the real-life experiences of people to whom this happened. Giving them space to do just that is a part of healing. Be it in documentary form, like Hubbard’s Birth of a Family, upon which this film is based, or here in Meadowlarks. These stories remind us that these events didn’t happen in the abstract, or in isolation, and the choice to dramatize these conversations in the present instead of re-enacting them in a period-set film helps remind us that we as a nation are still grappling with our troubled legacy.

As such, Meadowlarks joins films like Beans and series like Little Bird as essential viewing for audiences–both from Canada and elsewhere. Though there is hope to be found here, too, be prepared to shed some tears.

Meadowlarks screened as part of the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival. Head here to get all our That Shelf TIFF coverage.

The film will hit theatres in Canada later this fall, via Mongrel Media.