I have no business writing a column on technology. I’m what you call a luddite or at least a semi-luddite. Luddites were 19th-century followers of Ned Lud who organized textile workers in opposing certain types of automated machinery. Later, the term was extended to those who are stubborn in their technological ineptitude. That’s me. Ask anyone who works with me.

My aversion to technology does not extend to a refusal to use it or to see its importance and benefits. But my aversion may also sensitize me to the dangers of overreliance on it. In this, I am in good company. Many parents, educators and other professionals worry that people young and old are not only living “with” their phones but “in” them and “through” them.

All the world is filtered through the small screen. Sometimes you’ll see married couples at a restaurant; instead of talking to each other, they are looking at their phones. Young people base their self-esteem in the number of “likes” they receive on social media. Instead of being with others, many people, including the young, stay in their rooms glued to their phones.

What are they missing?

They are missing real human contact. Good conversation. Face-to-face exchanges of ideas and plans. A sense of other people’s humanity. Genuine affection. Pope Leo XIV drove home this point in a talk to young people attending an international youth festival in early August.

“No algorithm will ever replace a hug, a look, a real encounter – not with God, not with our friends and not with our family,” he said.

Pope Leo went on to encourage people to seek out not mere virtual encounters, but in-person encounters. He cited the example of the Blessed Virgin Mary who made a difficult journey to visit her cousin Elizabeth. Nothing replaces meeting others and being with others in person.

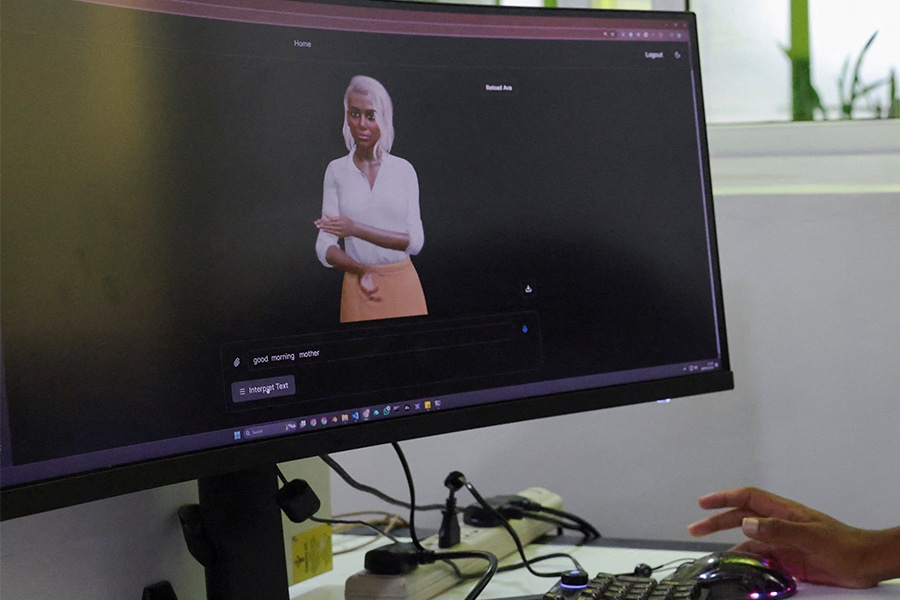

The advent of artificial intelligence has compounded the problem of online relationships. Of course, if I knew how to use AI, I could ask it to write my columns, homilies and correspondence. I would never fall behind in answering the many letters I receive, whether via “snail-mail” or electronically. But if I relied on AI, would my heart be in any of it or would it be a faint technological image of myself?

The dangers run deeper. Last May, the bishops of Maryland wrote a pastoral letter on AI that pointed out how AI can displace workers, incorporate biases into algorithms, manipulate the truth and ultimately be employed in lethal autonomous weapons which remove moral agency from decisions of life and death.

In a word, AI has made it more difficult to perceive what is real and what is unreal in the virtual world. And it has made it easier for its users to be deceived. This is not to deny the importance of AI, its legitimate uses and the potential benefits it can provide in research, medicine and many other fields. It is simply to point out that we are in “a brave new world.” As Pope Francis reminded us, “The inherent dignity of each human being and the fraternity that binds us together as members of the one human family must undergird the development of new technologies and serve as indisputable criterial for evaluating them before they are employed, so that digital progress can occur with due respect for justice and contribute to the cause of peace.”

Pope Leo teaches that “access to data – however extensive – must not be confused with intelligence, which necessarily ‘involves the person’s openness to the ultimate questions of life and death and reflects an orientation toward the True and Good.’ ”

Words to live by as we face “a brave new world.”

Read More Commentary

Copyright © 2025 Catholic Review Media