Subscribe now for full access and no adverts

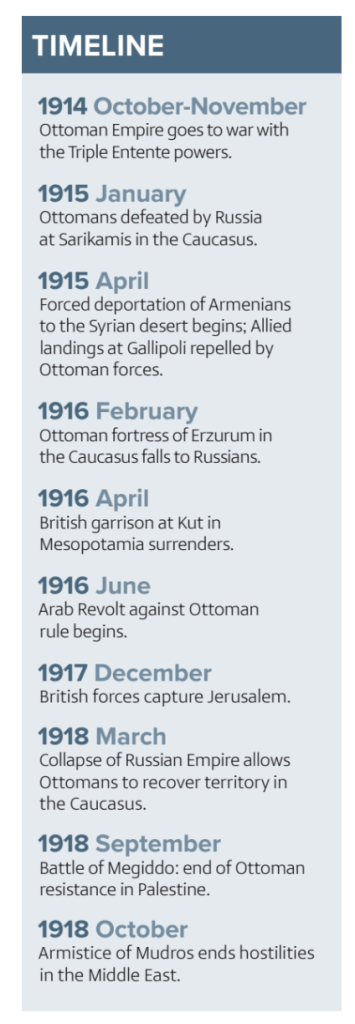

With the notable exceptions of Gallipoli and the Arab Revolt, the Ottoman Empire’s role in the First World War received limited attention for many years from military historians. Over the past two decades, this has ceased to be the case. The centenary of the war in 2014, combined with the rise of Islamic militancy, led to renewed interest in the Middle Eastern war and in the collapse of the empire once dubbed the ‘Sick Man of Europe’.

Research in the official Turkish archives has begun to shed light on forgotten campaigns. Low literacy levels in the empire’s mainly agricultural population – only 11% of male peasants could read and write – meant that rank-and-file Ottoman soldiers left almost no written records. However, there is an abundance of diaries and other narratives penned by the Turkish officer class and high-ranking German personnel attached to Ottoman forces. We now know much more about the Ottoman army’s performance in the last, ultimately disastrous conflict in which it took part.

Modern accounts stress the remarkable resilience of the empire’s troops. The Ottoman army had to contend with severe logistical and technological weaknesses and with shortages of trained manpower. The strategic thinking of its senior leadership was seriously flawed and the empire was plagued by administrative inefficiency and corruption. The army had suffered severe losses of men and equipment during the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913. The once-extensive Ottoman realm in south-east Europe was now reduced to Eastern Thrace, the area surrounding the capital Constantinople (modern Istanbul).

The resilience of the Ottoman troops – some pictured here armed with German MG 08 machine-guns – was one of the great surprises of the conflict in the Middle East.

The resilience of the Ottoman troops – some pictured here armed with German MG 08 machine-guns – was one of the great surprises of the conflict in the Middle East.Yet Ottoman forces held the line in a number of theatres in 1914-1918. They were in action in the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, Palestine, Syria, and Arabia, while also repelling allied landings in the Dardanelles and even sending help to Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. With 7,500 miles of borders and coastline to defend against the three Entente powers – Britain, France, and Russia – this was a highly vulnerable and overstretched empire.

The Ottoman decision for war marked the culmination of several decades of deepening ties with Germany, but was still not a foregone conclusion at the outbreak of European war. The German government was keen to see the Ottomans open a new front against Russia. It wanted to see an attack on the British-held Suez Canal and the launching of a holy war, in which Muslim subjects of the Entente powers would rise up against their colonial masters. In the event, the projected jihad failed to materialise. In December 1913, the Berlin government sent General Otto Liman von Sanders to head a German military mission, with a brief to take forward the training and reorganisation of the Ottoman army. But it took the transfer of two German warships, the Goeben and Breslau, and a substantial bribe to persuade the Ottoman regime to enter the conflict at the end of October 1914.

An unprepared combatant

The Ottoman Empire was perhaps the least prepared for war of all the major belligerent powers. A 1913 census revealed that, within the boundaries of modern Turkey, there were only 600 manufacturing firms with ten or more workers. Although its land area was almost five times the size of Germany and France, the empire possessed just 3,500 miles of single-track rail line. Poor transport links meant that it took two months for troops to traverse the 1,000-mile distance between Constantinople and the Caucasus front. Matters were no better for the Ottoman forces facing the British in Palestine. Ammunition – largely supplied by Germany, in the absence of a significant domestic munitions industry – had to be loaded and unloaded 12 times before it reached the Sinai Desert.

The Ottoman Empire stretched from south-eastern Europe to the borders of Persia, and from the Caucasus to the Yemen. Its 22 million people formed a complex patchwork of ethnicities and religions, but infrastructure – including the all-important rail network – was minimal and and unreliable, while large-scale industry was virtually non-existent.

The Ottoman Empire stretched from south-eastern Europe to the borders of Persia, and from the Caucasus to the Yemen. Its 22 million people formed a complex patchwork of ethnicities and religions, but infrastructure – including the all-important rail network – was minimal and and unreliable, while large-scale industry was virtually non-existent.In 1914, the Ottoman Empire had four armies, divided into either two, three or five corps. A typical corps consisted of three infantry divisions, an artillery regiment, and a cavalry division. On the outbreak of war, the army expanded from 200,000 to almost 500,000 men, as older exemptions from military service were removed. Over the next four years, the empire recruited some 2,900,000 troops. This was equivalent to about 13% of the population, which compares quite favourably with 15% in Austria-Hungary and just under 20% in Germany. It was achieved by lowering the minimum age of service from 20 to 18, and raising the maximum age from 45 to 50. But this was not the whole story.

Desertion – caused by the harsh conditions of enlistment and the prolongation of the war – was a serious problem. Arrears of pay, inadequate food, and lack of proper uniforms and footwear were constant grievances. An estimated 500,000 soldiers deserted, many of whom received aid from the local population or survived by forming robber bands in the countryside. Manpower shortages remained a problem, leading the authorities reluctantly to use Arab troops – regarded as inferior to Turks – on the Palestine front in the later stages of the war.

The Imperial German general Otto Liman von Sanders was appointed to train and reorganise the Ottoman army in December 1913.

The Imperial German general Otto Liman von Sanders was appointed to train and reorganise the Ottoman army in December 1913.By taking men away from agriculture and industry, the onset of war had a damaging effect on the fragile Ottoman economy. The conscription of able-bodied men caused a drop in productivity and slashed government tax revenues, deepening the budget deficit. To cover its costs, the regime became increasingly dependent on German subsidies and introduced extraordinary taxes and requisitioning of foodstuffs, which bore down heavily on the population.

Social divisions in the multiracial empire were exacerbated by the discriminatory nature of its recruitment policies. There was a distinction between ‘loyal’ Turkish and other Muslim populations on the one hand, and minority groups, such as Christians and Jews, on the other. Non-Muslims were viewed as less reliable and were more likely to be assigned to unarmed labour battalions, charged with repairing roads and moving supplies. Their ranks were progressively thinned by disease, exhaustion, and starvation.

The Ottoman commander Mustapha Kemal (later the leader of the Turkish national revival) warned of the dangers of a dependent relationship with Germany.

The Ottoman commander Mustapha Kemal (later the leader of the Turkish national revival) warned of the dangers of a dependent relationship with Germany.The Three Pashas

Heading the empire’s government from January 1913 was a trio of nationalist officials known as the ‘Young Turks’. They bore the title ‘pasha’ – historically given to high-ranking Ottoman political and military figures. Nominally under the authority of Sultan Mehmed V, their power base was a revolutionary political party, the Committee of Union and Progress. They were Enver Pasha (Minister of War and Chief of the General Staff),

Talaat Pasha (Minister of the Interior, later Grand Vizier or prime minister), and Cemâl Pasha (Minister of Marine, later commander of the Fourth Army in Palestine). All three were ambitious and ruthless, yet lacking essential qualifications for military leadership. Forced into exile after the Ottoman defeat, they met violent deaths: Talaat and Cemâl were assassinated, while Enver was killed fighting the Bolsheviks in Central Asia.

Arms and the man

The Ottoman army that went to war in 1914 was woefully ill-equipped. Cavalry were mostly mounted on undersized horses, suited to patrol and screening duties rather than massed charges. Artillery was in short supply, with Germany and Austria-Hungary being called on to provide heavy guns. The army’s best asset was its infantry, armed with various models of rifle, including German-made 7.65mm Mausers. Each infantry regiment was supposed to have a machine-gun company attached, but weapons were scarce at the start of the war.

The typical soldier was a Turkish Anatolian peasant – staunch in defending a fixed position and capable of surviving in a tough environment. Remarkably, there were no significant mutinies among the regular troops. The author and Middle East expert Gertrude Bell wrote in 1907 that ‘there is no more wonderful or pitiful sight than a Turkish regiment on the march; grey beards and half-fledged youth, ill clad and often barefoot, pinched and worn – and indomitable’. The evidence of campaign songs suggests that the prevailing mood among the Ottoman infantry was one of fatalistic resignation – far removed from the more familiar strains of ‘Pack up your troubles’ or ‘Keep right on to the end of the road’ on the Western Front.

Support services were sorely lacking. Each army corps possessed only one company of engineers. There was a rudimentary Ottoman air force from 1909, with military aviation units attached to the army and navy. At the end of 1916, the empire had some 90 aeroplanes, mostly supplied by Germany. The army’s medical organisation was poor, with inadequate medical care and poor hygiene leaving soldiers vulnerable to a range of diseases: malaria, typhus, and cholera contributed to high casualty figures. Given these limitations, it is remarkable that the Ottoman army endured for as long as it did.

The quality of officer leadership and training had improved since the Balkan Wars, with older and less effective commanders forced to retire. Nonetheless, this was an army that relied on numbers rather than skill to achieve results, leading to heavy casualties that it could ill afford. This was particularly true at junior officer level. There was no sizeable pool of experienced professionals who could replace those killed in action.

Ottoman admiration for German military efficiency was balanced by resentment of its more powerful ally’s dominance. In 1917-1918, Ottoman forces in Palestine were placed under the overall leadership of former Chief of the German General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn, who was succeeded by Liman von Sanders. This dependent relationship created tensions, especially as defeat approached. Ottoman commander Mustapha Kemal (later to be granted the surname Atatürk, or ‘Father of the Turks’, for leading the Turkish national revival after the empire’s collapse) warned that Germany should not be allowed to ‘prolong this war to the point of reducing Turkey to the position of a colony in disguise’.

The Ottoman army that went to war in 1914 was woefully ill-equipped, with cavalry mostly mounted on undersized horses.

The Ottoman army that went to war in 1914 was woefully ill-equipped, with cavalry mostly mounted on undersized horses.Taking the offensive

The strengths and weaknesses of the Ottoman military are well-illustrated by the campaign in the Caucasus, which began when Russian forces crossed the frontier in November 1914. Although he lacked experience of field command, War Minister Enver Pasha – the dominant figure in the empire’s government – took personal charge of the Third Army. He promptly embarked on a misconceived attempt to capture the town of Sarikamis in eastern Anatolia. With three army corps, he aimed to imitate Germany’s masterly encirclement of Russian forces at Tannenberg, in East Prussia, a few months earlier. To attempt this in mountainous terrain in the depth of winter was to invite disaster. The combined effects of frostbite, fatigue, and disease took a heavy toll on the 118,000-strong Ottoman army. Estimates of casualties ranged from 60,000 to 90,000.

A German-built Halberstadt D.III of the Ottoman 15th Fighter Flight Squadron. By the end of 1916, the empire had some 90 aeroplanes, mostly supplied by Germany.

A German-built Halberstadt D.III of the Ottoman 15th Fighter Flight Squadron. By the end of 1916, the empire had some 90 aeroplanes, mostly supplied by Germany.The stoicism of Enver’s troops – those struggling through the deepest snow were bizarrely instructed to leave their packs and greatcoats behind – contrasted with the folly and self-interest of their commander. Leaving the army to its fate, Enver headed home to manage the news so that his own culpability was obscured. There was a further baleful consequence of the Sarikamis debacle. The government blamed the defeat on the alleged disloyalty of Armenian troops, using this as a pretext for the wholesale deportation of their countrymen and -women to the Syrian desert in April 1915. In an episode widely regarded as the first genocide of the 20th century, somewhere between 600,000 and 1.5 million Armenians lost their lives in forced marches over inhospitable terrain.

Ottoman infantry defend a trench during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in 1917.

Ottoman infantry defend a trench during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in 1917.Further disaster followed for the Ottomans in February 1916, with the loss of the key Caucasus fortress of Erzurum. The garrison was protected by two impressive rings of fortifications – but the Russian assault came from the east and through the mountainous terrain to the north, where the defences were weaker. The Russians brought up artillery to reduce the perimeter forts one by one, forcing the defenders to fall back. With their defences crumbling, the Ottomans evacuated the fortress, leaving some 10,000 casualties.

The unrealistic nature of Ottoman strategy was demonstrated on other fronts. A bid to seize the Suez Canal in February 1915, which would have inflicted a crippling blow on Britain’s imperial communications, met with initial success. The expeditionary force marched by night across the Sinai, when it was cooler, and German engineers dug wells in the arid landscape. The Ottomans crossed the canal – but, unable to retain control of their bridgehead on the western bank, they were forced to retreat. A further attempt on the waterway in August 1916 also ended in failure. Meanwhile, in the desert region of the Hejaz – an area that equates to western Saudi Arabia today – Ottoman forces were left stretched out along an 800-mile single-track railway from Damascus to Medina. This proved vulnerable to guerrilla attacks after the start of the Arab Revolt in mid-1916.

The price of war

The Gallipoli Campaign of 1915-1916 was the high point of the Ottoman war effort. A Franco-British attempt in March 1915 to take control by naval action of the Dardanelles, part of the vital waterway that connects the Mediterranean to the Black Sea, was repelled by a combination of sea mines and well-positioned and rapidly reinforced artillery. The Ottoman army’s defeat of the allied expeditionary force’s attempt to secure a foothold on the peninsula was a major victory. It was won, however, at a heavy cost. Some 86,500 Ottoman troops were killed and at least 165,000 incapacitated by wounds and disease – figures which included some of the army’s best-equipped and most experienced personnel.

Australian troops charge a Turkish trench during the Gallipoli campaign of 1915-1916. The defeat of the allied expeditionary force was a major Ottoman victory – but it was won at a heavy cost.

Australian troops charge a Turkish trench during the Gallipoli campaign of 1915-1916. The defeat of the allied expeditionary force was a major Ottoman victory – but it was won at a heavy cost. The Mesopotamian front saw another Ottoman victory in the spring of 1916. This was the surrender of a British garrison at Kut al-Imara – the greatest British humiliation in the field since the capitulation of Yorktown to the American revolutionary army in 1781. British forces had gained initial superiority in what is now southern Iraq, winning control of Basra but overreaching themselves when they continued up the River Tigris towards Baghdad. Retreating to Kut, General Charles Townshend’s force endured a 145-day siege, capitulating only when starvation became a certainty.

The following year of 1917 saw a short-lived Ottoman recovery. Russia’s withdrawal from the Caucasus, following the Bolshevik revolution, enabled Turkish forces to regain territory. Meanwhile in Palestine, Ottoman stubbornness in defence was highly effective in resisting two attempts to encircle them at Gaza in March-April 1917. In the Second Battle of Gaza, in which the British deployed armour and gas shells, Ottoman troops held out during three days of fighting. The British lost three of their eight tanks and suffered three times the number of Ottoman casualties.

The reversal led to a change in the British high command. General Edmund Allenby built up his strength and improved his communications and logistics in readiness for Third Gaza in November 1917. The use of mobile cavalry and better coordination of infantry and artillery paid off. The Royal Flying Corps gained air superiority, using newly introduced Bristol F.2B fighters in effective attacks on Ottoman troops, railway junctions, aerodromes, and other targets.

Turkish carts and gun carriages litter the road following the crushing Ottoman defeat at Megiddo, the climactic battle of the Sinai and Palestine campaign, in September 1918.

Turkish carts and gun carriages litter the road following the crushing Ottoman defeat at Megiddo, the climactic battle of the Sinai and Palestine campaign, in September 1918.The victory was followed by the taking of Jerusalem the next month. The imbalance of resources took its toll during 1918, preparing the ground for a crushing Ottoman defeat in September at Megiddo, in Palestine. British and Indian infantry advanced under cover of a rolling artillery barrage to punch a hole in the Ottoman lines. In their wake came the Desert Mounted Corps, who threatened to encircle the Ottoman forces. As the latter retreated, they came under sustained assault from the air, leaving behind a trail of abandoned transports and equipment. In October, the Armistice of Mudros ended the fighting in the Middle East and led to the demobilisation of the Ottoman army and the allied occupation of Constantinople.

Doomed from the start?

Economically backward, politically unreformed, and riven with internal dissension, the Ottoman Empire was ill-adapted to the challenges of modern warfare. The unrealistic ambitions of its senior leadership added to the strains of defending disparate and sprawling territories. The Ottomans were fortunate that Britain, France, and Russia could not spare men and matériel in sufficient quantities to inflict a decisive defeat on them at an earlier stage. This allowed the Ottoman army to sustain a largely defensive war. Allied troops developed a grudging respect for the qualities of the opponent they knew as ‘Johnny Turk’. Brave and tenacious, though starved of resources, they fought a losing battle well.

Graham Goodlad has taught history and politics for more than 30 years. He is a freelance writer and a regular contributor to MHM.

Further reading:

• The Ottoman Endgame: War, Revolution and the Making of the Modern Middle East, 1908-1923 (Sean McMeekin, Allen Lane/Penguin, 2015).

• The Fall of the Ottomans: the Great War in the Middle East, 1914-1920 (Eugene Rogan, Allen Lane/Penguin, 2015).

In the next issue of MHM: Continuing our series on Imperial Germany’s Great War allies, Graham Goodlad examines the record of the Bulgarian army.

All images: Wikimedia Commons