Hundreds of feet under the surface in north Alabama, an experienced caver can step into passageways that have never seen a human footprint.

“The only other ways to get that kind of experience would be in space or the depths of the ocean,” said Dr. Hazel Barton, the Loper Endowed Professor of Geological Sciences. The thrill of first discovery in space or an ocean trench is out of reach for the average person’s hobby budget.

Hazel Barton traversing the Rift Passage during a camp trip in Lechuguilla Cave, New Mexico. Photo credit: Dave Bunnell

Hazel Barton traversing the Rift Passage during a camp trip in Lechuguilla Cave, New Mexico. Photo credit: Dave Bunnell

“In caving, you only need a helmet and a light, and the knowledge of how not to mess up. And in Alabama, you need about 1,000 feet of rope.”

As part of the new Built by Bama core curriculum at The University of Alabama, Barton will be using the unique geology of Alabama’s 9,000 caves to explore the fundamental principles of science in a new course this fall.

Designed for non-science majors, the Science of Caves (GEO 106) blends geology, biology, chemistry, philosophy and history to help students develop critical thinking skills and a deeper appreciation for the scientific process.

“I want to teach students how to look at the world through the eyes of a scientist,” Barton said. “How information is fed to us, how we process that information, how we act on that information.”

Listen to 92.5FM’s Capstone Conversation with Dr. Hazel Barton

The world is a cave

The course is meant to show off the breadth of science, and caves are perfect for that, Barton said. Her research lab is multidisciplinary and integrative by necessity. She is a trained medical microbiologist, but to learn the microbial secrets of caves, she trained in the geology, chemistry and physics of caves and cave exploration.

From Neolithic humans leaving handprints on cave walls through space exploration, Barton sees caves as a thread from the beginning of human history to its future. But the course will not be a semester of memorization.

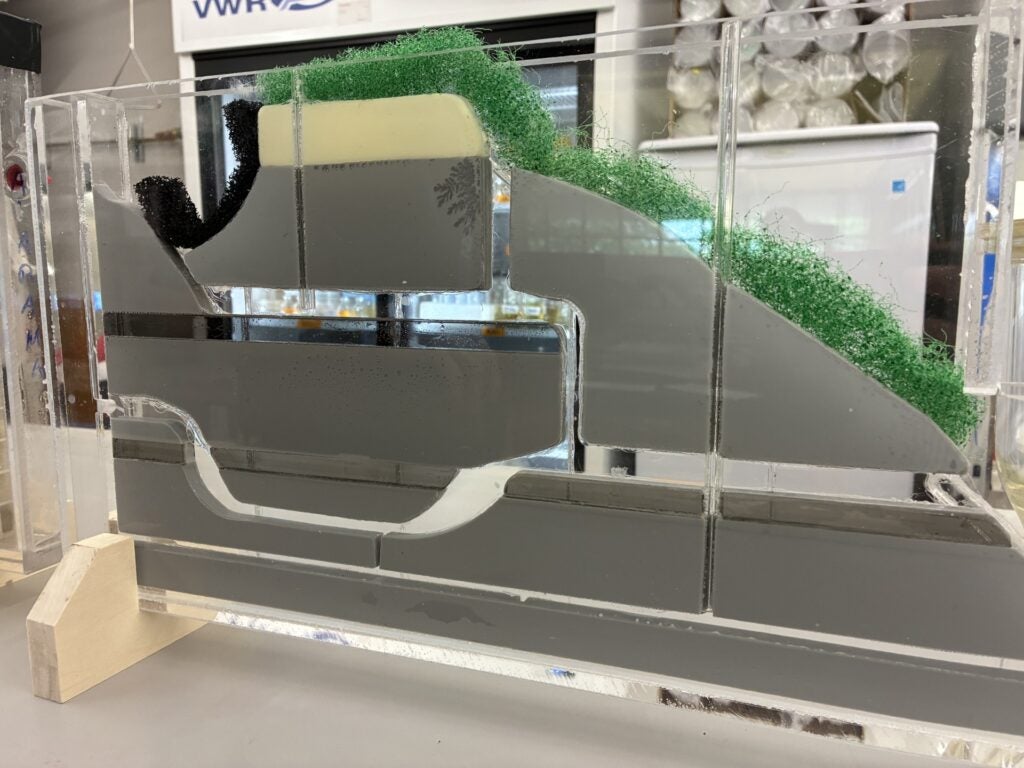

Students will complete hands-on labs that use caves to learn how to identify a cave-based problem and then devise problem-solving strategies. For example, a custom-made hydrology model based on Alabama’s caves will require students to figure out how to rescue cavers stranded in a flooded underground chamber.

In another lab, students will learn to use a specialized tool to create a cave map of Beville Hall and then render it in Adobe Illustrator. Another time, they will learn to tie knots in rope, calculate the strength of the rope and then test the physics of knots in rope in a lab on campus.

A cave is more than a cave

Caves are mined and destroyed on a regular basis. Barton’s research mines them for information, and she believes understanding caves is important for everyone. From work in caves around the world, her lab has developed breakthroughs in biotechnology, carbon sequestration, potential solutions to nylon recycling and how cave microbes might lead to more efficient rare earth extraction.

Graduate student Katey Bender collects biological samples from Lake Castrovalva in Lechuguilla Cave, New Mexico. Photo credit: Hazel Barton

Graduate student Katey Bender collects biological samples from Lake Castrovalva in Lechuguilla Cave, New Mexico. Photo credit: Hazel Barton

Furthermore, 25% of our drinking water flows through caves as part of the earth’s natural filtration system. In some cities, nearly 100% of municipal drinking water comes from cave groundwater.

Imagine drinking water filtered through an old, decomposing refrigerator someone dumped down a cave believing that out of sight was as good as gone.

“Not every place has caves, but where there are caves, everything in that area is interdependent,” Barton said. Humans live in that ecosystem, and if runoff from a chicken farm goes down the wrong hole, then it is in the drinking water as well.

Why Alabama?

“I definitely moved to Alabama for the caves,” Barton said. Earlier this year, Barton won the Lew Bicking Award, America’s most prestigious award for cave exploration.

Where Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia come together, often called the TAG region, impermeable sandstone caps thick layers of limestone. Water flows off sandstone ridges and then cuts through the softer limestone, hollowing out deep vertical shafts and huge underground chambers.

The TAG area contains an estimated 50,000 caves — more than some continents. Many of these caverns have not been fully explored or mapped. If the course is successful, Barton imagines an honors section in the future where students will actually get to explore and inventory some of Alabama’s caves.

“There’s no technology that can tell you what a cave looks like,” Barton said. “The only way to know is to go in and start mapping it.”

From left, Hazel Barton, Johanna Kovarik, post-doctoral fellow George Breley, and graduate student Katey Bender in the Chandelier Ballroom of Lechuguilla Cave, New Mexico. Photo credit: Hazel Barton

From left, Hazel Barton, Johanna Kovarik, post-doctoral fellow George Breley, and graduate student Katey Bender in the Chandelier Ballroom of Lechuguilla Cave, New Mexico. Photo credit: Hazel Barton

She hopes that students in her course will experience that thrill of discovery and carry it with them into their eventual careers. And if she manages to convert a few to science majors, so much the better.